The 30 Best Country, Folk and Americana Albums of 2023

Photos by Jackie Lee Young & D'Angelo Isaac

This year, singer/songwriter albums ruled the kingdom. From January through December, the country, folk and Americana genres were producing some of the most arresting and moving projects. We’ve covered many of these LPs in some capacity or another, whether it was through a review or a profile, and, as 2024 pushes in on us harder than ever, we’re still thinking about them. From the perennial triumphs of Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit to Margo Price’s sonic rebirth to a masterpiece from Jess Williamson, we’ve gone through the last 12 months and picked out our favorite outlaw, Western, troubadour, balladeer and everything-in-between records from that span. So, without further ado, here are the 30 best country, folk and Americana albums of 2023. —Matt Mitchell, Music Editor

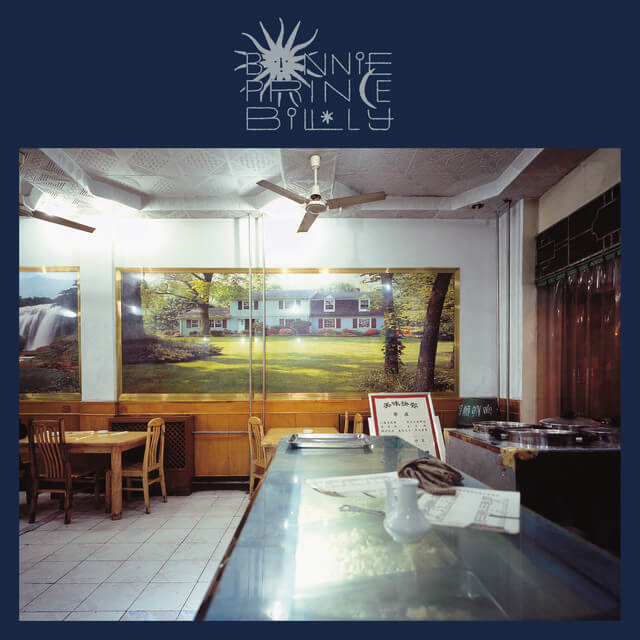

Bonnie “Prince” Billy: Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You

The latest studio album from Will Oldham—aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy—is an emotional folk journey with a great thematic landscape. Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You makes good on sparseness in all of the loveliest ways. “Does it get any better?” Oldham ponders on “Bananas,” while a sense of lingering grief populates much of the record. In an extensive catalog, Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You sticks out. It’s Oldham’s first album of any kind since his 2021 collaboration with Bill Callahan, and it’s his first bonafide, solo Bonnie “Prince” Billy album since I Made a Place in 2019. There’s much to be said about the construction of these songs, which often unfurl only through pairings of vocalizations and a lone acoustic guitar. Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You is a singer/songwriter record down to the bone, and it’s one of Bonnie “Prince” Billy’s starkest and very best. —Matt Mitchell

The latest studio album from Will Oldham—aka Bonnie “Prince” Billy—is an emotional folk journey with a great thematic landscape. Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You makes good on sparseness in all of the loveliest ways. “Does it get any better?” Oldham ponders on “Bananas,” while a sense of lingering grief populates much of the record. In an extensive catalog, Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You sticks out. It’s Oldham’s first album of any kind since his 2021 collaboration with Bill Callahan, and it’s his first bonafide, solo Bonnie “Prince” Billy album since I Made a Place in 2019. There’s much to be said about the construction of these songs, which often unfurl only through pairings of vocalizations and a lone acoustic guitar. Keeping Secrets Will Destroy You is a singer/songwriter record down to the bone, and it’s one of Bonnie “Prince” Billy’s starkest and very best. —Matt Mitchell

Bonnie Montgomery: River

The latest LP from Fayetteville, Arkansas country songstress Bonnie Montgomery is dazzling as all get-out, largely for how it conjures the honky-tonk grandiosity that singers like Connie Francis and Barbara Mandrell honed 50 years ago. And, yet, Montgomery’s River blends those timeless sonics with a contemporary attitude and penchant for crystallized melodies. Montgomery is a brilliant storyteller, as she deftly blends the autobiographical with a captivating embellishment. The result is a mirage of visceral imagery and interwoven stories anyone can latch onto. Tracks like “Modern-Day Cowgirl’s Dream” and “Leon” are versatile yet headstrong, and Montgomery’s soulful lilt becomes multi-dimensional over and over. It helps that she is a trained opera singer, which makes her turn towards this glimmer of outlaw music all the more stirring. Piecing together bluegrass, gospel, pop-country and soul, River is the kind of record that ought to soundtrack the entire world over, not just the corner of the South it first came to life in. —Matt Mitchell

The latest LP from Fayetteville, Arkansas country songstress Bonnie Montgomery is dazzling as all get-out, largely for how it conjures the honky-tonk grandiosity that singers like Connie Francis and Barbara Mandrell honed 50 years ago. And, yet, Montgomery’s River blends those timeless sonics with a contemporary attitude and penchant for crystallized melodies. Montgomery is a brilliant storyteller, as she deftly blends the autobiographical with a captivating embellishment. The result is a mirage of visceral imagery and interwoven stories anyone can latch onto. Tracks like “Modern-Day Cowgirl’s Dream” and “Leon” are versatile yet headstrong, and Montgomery’s soulful lilt becomes multi-dimensional over and over. It helps that she is a trained opera singer, which makes her turn towards this glimmer of outlaw music all the more stirring. Piecing together bluegrass, gospel, pop-country and soul, River is the kind of record that ought to soundtrack the entire world over, not just the corner of the South it first came to life in. —Matt Mitchell

Buck Meek: Haunted Mountain

Buck Meek works often through love with a deluge of mythology and naturality and spiritual forces across Haunted Mountain. It’s the richest part of the work altogether, beyond the sonic construction of the songs themselves. On “Undae Dunes,” he muses on UFOs and spaceships, singing “Years flew by with enigmatic beauty, but every night he’d think of Suzy. Red sky filled with rockets, Jim still flies with a silver locket.” On “Lagrimas,” he ushers in nods to sorcery and vintage, otherworldly safekeepings in order to find reconnections with a dead loved one. “Saving my tears in a bottle, saving my nickels and dimes to give to the old necromancer who knows how to read and write,” Meek sings. “Dip your quill into my well, tears fall as you write. His wings will carry my words so heavy to the sky.” In his world, sincerity is evergreen and beautiful, the first real step towards achieving authentic bonds with the people and places you set out to love. There’s an intentionality behind the playfulness on Haunted Mountain, and it’s something that Meek taps into often—unraveling its integrality in friendships and romances, exploring the freedom and flexibilities of childlike wonder in healthy relationships. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Buck Meek works often through love with a deluge of mythology and naturality and spiritual forces across Haunted Mountain. It’s the richest part of the work altogether, beyond the sonic construction of the songs themselves. On “Undae Dunes,” he muses on UFOs and spaceships, singing “Years flew by with enigmatic beauty, but every night he’d think of Suzy. Red sky filled with rockets, Jim still flies with a silver locket.” On “Lagrimas,” he ushers in nods to sorcery and vintage, otherworldly safekeepings in order to find reconnections with a dead loved one. “Saving my tears in a bottle, saving my nickels and dimes to give to the old necromancer who knows how to read and write,” Meek sings. “Dip your quill into my well, tears fall as you write. His wings will carry my words so heavy to the sky.” In his world, sincerity is evergreen and beautiful, the first real step towards achieving authentic bonds with the people and places you set out to love. There’s an intentionality behind the playfulness on Haunted Mountain, and it’s something that Meek taps into often—unraveling its integrality in friendships and romances, exploring the freedom and flexibilities of childlike wonder in healthy relationships. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

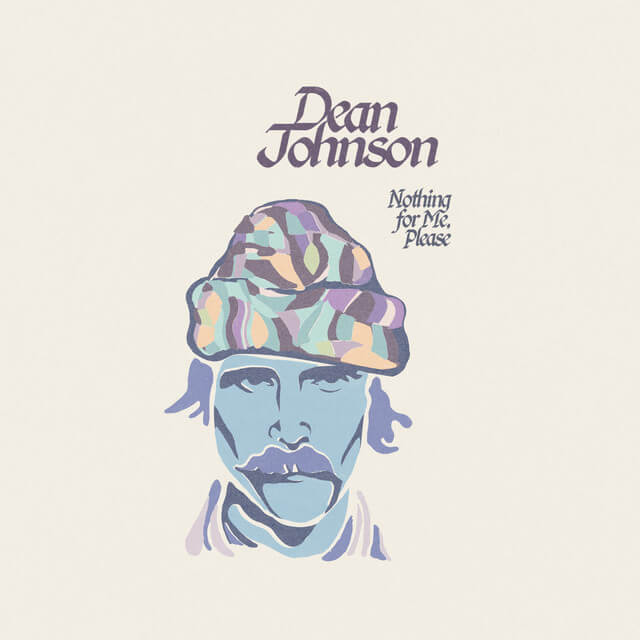

Dean Johnson: Nothing For Me, Please

Hailing from Washington State, folk troubadour Dean Johnson has been around for almost two decades. Today, his long-awaited debut LP, Nothing For Me, Please finally arrives. Conjuring the best pieces of John Prine, Townes Van Zandt and Blaze Foley, Nothing For Me, Please is not your prototypical country record. Instead, it’s a widely spun tapestry of colored lands where curious eyes and hearts roam. Songs like “Faraway Skies” and “True Love” are immediate bedrocks of contemporary folk playlists. And, at the center of it all, remains Johnson’s awing vocal, which careens through octaves into a breathtaking falsetto you can’t help but fall in love with. Each song tells a complete tale, and Johnson’s debut album Nothing For Me, Please is without filler. At a concise nine chapters, the album rings in like a portrait of his life thus far, which makes sense, given that the oldest entry in the tracklist was written as long ago as 2004. Standout song “Shouldn’t Say Mine” is a pure acoustic bliss with soft rock percussion that perfectly compliments Johnson’s voice. The song could be in communion with anything from Sweet Baby James-era James Taylor or anything Jim Croce put out in the Nixon years. As a high-pitched piano rings out, Johnson laments: “I held you too tight, my weakness it showed / I was in your way trying to get close / You’re after my world, a rolling stone / Alright, alright, I’ll leave you alone / Too much and not enough, close enough to tear each other up.” Johnson is no longer Seattle’s best-kept secret. The honest, warm storytelling on Nothing For Me, Please is sure to gain him a few more fans, and for good reason. —Matt Mitchell

Hailing from Washington State, folk troubadour Dean Johnson has been around for almost two decades. Today, his long-awaited debut LP, Nothing For Me, Please finally arrives. Conjuring the best pieces of John Prine, Townes Van Zandt and Blaze Foley, Nothing For Me, Please is not your prototypical country record. Instead, it’s a widely spun tapestry of colored lands where curious eyes and hearts roam. Songs like “Faraway Skies” and “True Love” are immediate bedrocks of contemporary folk playlists. And, at the center of it all, remains Johnson’s awing vocal, which careens through octaves into a breathtaking falsetto you can’t help but fall in love with. Each song tells a complete tale, and Johnson’s debut album Nothing For Me, Please is without filler. At a concise nine chapters, the album rings in like a portrait of his life thus far, which makes sense, given that the oldest entry in the tracklist was written as long ago as 2004. Standout song “Shouldn’t Say Mine” is a pure acoustic bliss with soft rock percussion that perfectly compliments Johnson’s voice. The song could be in communion with anything from Sweet Baby James-era James Taylor or anything Jim Croce put out in the Nixon years. As a high-pitched piano rings out, Johnson laments: “I held you too tight, my weakness it showed / I was in your way trying to get close / You’re after my world, a rolling stone / Alright, alright, I’ll leave you alone / Too much and not enough, close enough to tear each other up.” Johnson is no longer Seattle’s best-kept secret. The honest, warm storytelling on Nothing For Me, Please is sure to gain him a few more fans, and for good reason. —Matt Mitchell

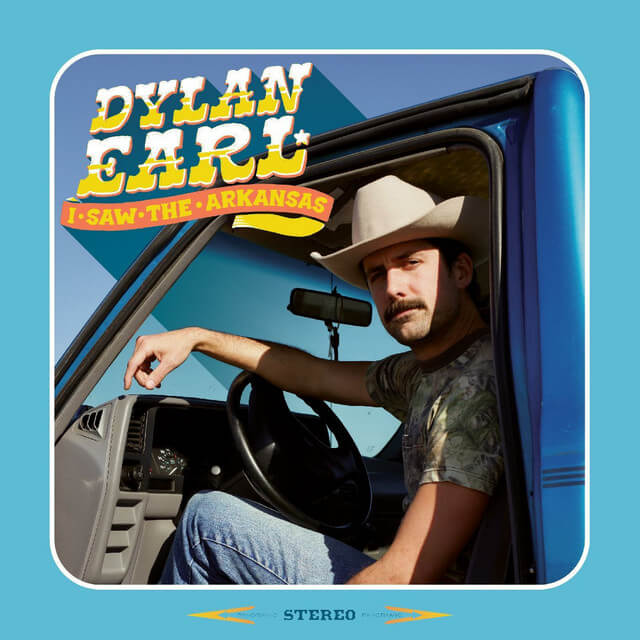

Dylan Earl: I Saw the Arkansas

The third album from Fayetteville, Arkansas singer/songwriter Dylan Earl is a balladeering triumph, as I Saw the Arkansas merges the cosmos of pedal steel-driven country rock with his longtime folk troubadour inclinations. The result is miraculous, idiosyncratic and nuanced, as Earl tells stories that feel far away yet eerily familiar all the same. A song like “Buddy” arrives like a mirage of brotherhood and the romance of carrying memories across towns, crowds and long drives that’ll remedy homesickness. There is a battalion of trailblazers churning out socially conscious country tunes in the South, and Earl is one of them. Though his sound is akin to Randy Travis and Conway Twitty, Earl’s songwriting has an edge to it that is hard to replicate, there’s a beautiful chaos balanced by the metronome that is Earl’s portrait of an America untouched by contemporary pop country that you can hear on “White Painted Trees” and “Blessing in Disguise. In turn, I Saw the Arkansas is a raucous, methodical and beautiful honky-tonk joint that’s lived a thousand lives yet still dares to find new highways to ramble across. With baritones that skate across octaves like a familiar voice spilling from truck stereos, Earl is a torchbearer among the swamps of a country underground that is meteorically, emphatically and lovingly rising to the surface. —Matt Mitchell

The third album from Fayetteville, Arkansas singer/songwriter Dylan Earl is a balladeering triumph, as I Saw the Arkansas merges the cosmos of pedal steel-driven country rock with his longtime folk troubadour inclinations. The result is miraculous, idiosyncratic and nuanced, as Earl tells stories that feel far away yet eerily familiar all the same. A song like “Buddy” arrives like a mirage of brotherhood and the romance of carrying memories across towns, crowds and long drives that’ll remedy homesickness. There is a battalion of trailblazers churning out socially conscious country tunes in the South, and Earl is one of them. Though his sound is akin to Randy Travis and Conway Twitty, Earl’s songwriting has an edge to it that is hard to replicate, there’s a beautiful chaos balanced by the metronome that is Earl’s portrait of an America untouched by contemporary pop country that you can hear on “White Painted Trees” and “Blessing in Disguise. In turn, I Saw the Arkansas is a raucous, methodical and beautiful honky-tonk joint that’s lived a thousand lives yet still dares to find new highways to ramble across. With baritones that skate across octaves like a familiar voice spilling from truck stereos, Earl is a torchbearer among the swamps of a country underground that is meteorically, emphatically and lovingly rising to the surface. —Matt Mitchell

Esther Rose: Safe to Run

Safe to Run follows Esther Rose’s distinct style of making country music coupled with self-constraints. Songs like “Handyman” from You Made It This Far feature a swing-like rhythm conjured from Lyle Werner’s beautiful fiddle and Matt Bell’s lap steel. “Without You” from How Many Times is emblematic of Rose’s vocal dips and unique phrasing. The sound itself has a clarity that’s different from the bit of graininess of her former projects, with hints of influence from ’70s folk and blues. Long-time collaborator Ross Farbe took on the producer role for Safe to Run, adding synths and various textures to exemplify the tracklist’s deeper sound. The album still has her trademark live sound, this time paired with multi-tracking and overdubs. Rose dives into themes of environment, spiritual displacement and sexism in the music industry. “Chet Baker” lingers on the image of a dive bar, and the title track connects personal feelings towards the world with the looming grief and dread of climate disaster; nods of Elliot Smith are heard in the vocals of “Stay,” and there’s a glittering pop sheen alive on “Insecure.” —Rayne Antrim [Read our feature]

Safe to Run follows Esther Rose’s distinct style of making country music coupled with self-constraints. Songs like “Handyman” from You Made It This Far feature a swing-like rhythm conjured from Lyle Werner’s beautiful fiddle and Matt Bell’s lap steel. “Without You” from How Many Times is emblematic of Rose’s vocal dips and unique phrasing. The sound itself has a clarity that’s different from the bit of graininess of her former projects, with hints of influence from ’70s folk and blues. Long-time collaborator Ross Farbe took on the producer role for Safe to Run, adding synths and various textures to exemplify the tracklist’s deeper sound. The album still has her trademark live sound, this time paired with multi-tracking and overdubs. Rose dives into themes of environment, spiritual displacement and sexism in the music industry. “Chet Baker” lingers on the image of a dive bar, and the title track connects personal feelings towards the world with the looming grief and dread of climate disaster; nods of Elliot Smith are heard in the vocals of “Stay,” and there’s a glittering pop sheen alive on “Insecure.” —Rayne Antrim [Read our feature]

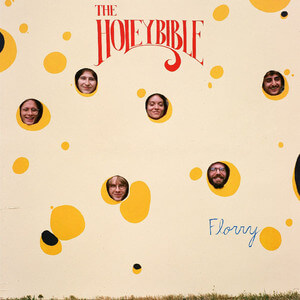

Florry: The Holey Bible

The opening riot from Florry’s recent LP The Holey Bible begins with an assertion: “Pull the car over, I gotta puke,” Sheridan Frances Arthur Medosch cries out with a bevy of bandmate voices wrapped around theirs. “You’re no good at driving high, kick me out the door as soon as we stop, I’m not tryna mess up my ride.” Florry are Philadelphia down to the bone, yet their new album is, just maybe, the most intoxicating country release of 2023 altogether. The project is catalyzed by “Drunk and High,” the lead track that is, through and through, an absolute trip. It conjures the best and rawest touchstones of the golden era of country-rock, and through Medosch and John Murray’s dueling guitar work, the song roars. It’s emphatic, moving storytelling that is as familiar as it is dreamlike. When Florry sing about blowing chunks on the side of the road, you want an invitation to that party. They make it seem like the coolest, nastiest thing in the world. “Drunk and High” is an anthem, and anything with a fiddle in it is good in my book. Likewise, tracks like “Cowgirl Giving,” “Take My Heart” and “”Big Winter” raise the stakes even further, embroidering traditional country music soundscapes with contemporary flair and catchiness. It’s sometimes hard to describe what makes an album like The Holey Bible work on all fronts, but I promise—if you listen just once—you’ll be hooked without a hitch. —Matt Mitchell

The opening riot from Florry’s recent LP The Holey Bible begins with an assertion: “Pull the car over, I gotta puke,” Sheridan Frances Arthur Medosch cries out with a bevy of bandmate voices wrapped around theirs. “You’re no good at driving high, kick me out the door as soon as we stop, I’m not tryna mess up my ride.” Florry are Philadelphia down to the bone, yet their new album is, just maybe, the most intoxicating country release of 2023 altogether. The project is catalyzed by “Drunk and High,” the lead track that is, through and through, an absolute trip. It conjures the best and rawest touchstones of the golden era of country-rock, and through Medosch and John Murray’s dueling guitar work, the song roars. It’s emphatic, moving storytelling that is as familiar as it is dreamlike. When Florry sing about blowing chunks on the side of the road, you want an invitation to that party. They make it seem like the coolest, nastiest thing in the world. “Drunk and High” is an anthem, and anything with a fiddle in it is good in my book. Likewise, tracks like “Cowgirl Giving,” “Take My Heart” and “”Big Winter” raise the stakes even further, embroidering traditional country music soundscapes with contemporary flair and catchiness. It’s sometimes hard to describe what makes an album like The Holey Bible work on all fronts, but I promise—if you listen just once—you’ll be hooked without a hitch. —Matt Mitchell

Fust: Genevieve

The latest LP from Durham, NC-based country outfit Fust is a sweet amalgam of soulful alt-rock tunes set adrift with Southern balladry and Crazy Horse-style riffs. Featuring guest appearances from Michael Cormier-O’Leary, Indigo De Souza and members of Wednesday, Genevieve is a gracious, brilliant collection of tracks that will stick with you: “Violent Jubilee” arrives as a piano-facing cut that then spins itself into a distorted, gothic bedrock of Americana inflections and mid-century rock ’n’ roll architecture. Featuring the handiwork of fellow Tar Heels Jake Lenderman and Xandy Chelmis of Wednesday and MJ Lenderman, Fust pack the sweet, soulful alt-rock emblem “Trouble” with Crazy Horse-style riffs and a limitless pedal steel. “Trouble,” though much more handsome and steadfast in its North Carolina twang (which Fust brought to life at Drop of Sun Studios in Asheville), is a perfect encapsulation of the compositional brilliance of Fust’s underrated yet massive album Genevieve altogether. —Matt Mitchell

The latest LP from Durham, NC-based country outfit Fust is a sweet amalgam of soulful alt-rock tunes set adrift with Southern balladry and Crazy Horse-style riffs. Featuring guest appearances from Michael Cormier-O’Leary, Indigo De Souza and members of Wednesday, Genevieve is a gracious, brilliant collection of tracks that will stick with you: “Violent Jubilee” arrives as a piano-facing cut that then spins itself into a distorted, gothic bedrock of Americana inflections and mid-century rock ’n’ roll architecture. Featuring the handiwork of fellow Tar Heels Jake Lenderman and Xandy Chelmis of Wednesday and MJ Lenderman, Fust pack the sweet, soulful alt-rock emblem “Trouble” with Crazy Horse-style riffs and a limitless pedal steel. “Trouble,” though much more handsome and steadfast in its North Carolina twang (which Fust brought to life at Drop of Sun Studios in Asheville), is a perfect encapsulation of the compositional brilliance of Fust’s underrated yet massive album Genevieve altogether. —Matt Mitchell

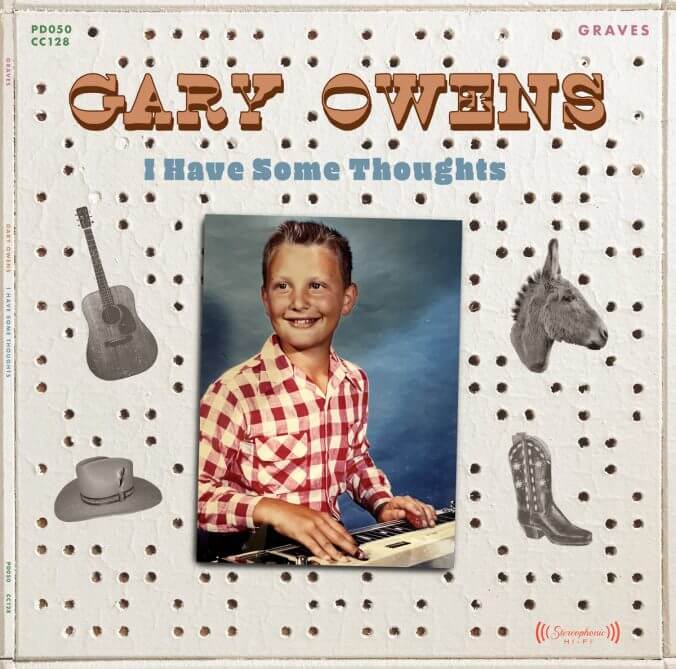

Graves: Gary Owens: I Have Some Thoughts

Graves, the project of California singer/songwriter Greg Olin, has added another LP to his near-20-year arsenal. Gary Owens: I Have Some Thoughts is a rich, 16-track album rife with sweet, digestible country zingers caked in West Coast haze and Pacific Highway joy. The language across these songs is hypnotic, recalling some of David Berman’s greatest works. “Woo A Fool” is wide-eyed and reflective, while “Little Dumb Dogs” is a ditty that’ll tug your heartstrings and yank a grin from your lips. On Gary Owens: I Have Some Thoughts, love is found and lost, time ticks on, sadness finds a niche and birds sing loudly for all. Olin’s work here is some of the best Western and folk music you’ll hear all year, and you’d be remiss to let it float under your radar any longer. —Matt Mitchell

Graves, the project of California singer/songwriter Greg Olin, has added another LP to his near-20-year arsenal. Gary Owens: I Have Some Thoughts is a rich, 16-track album rife with sweet, digestible country zingers caked in West Coast haze and Pacific Highway joy. The language across these songs is hypnotic, recalling some of David Berman’s greatest works. “Woo A Fool” is wide-eyed and reflective, while “Little Dumb Dogs” is a ditty that’ll tug your heartstrings and yank a grin from your lips. On Gary Owens: I Have Some Thoughts, love is found and lost, time ticks on, sadness finds a niche and birds sing loudly for all. Olin’s work here is some of the best Western and folk music you’ll hear all year, and you’d be remiss to let it float under your radar any longer. —Matt Mitchell

Hayden Pedigo: The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored

Hayden Pedigo’s latest album, The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored, arrives beautiful and damning in its vulnerability—all without a single word uttered across the record’s 37-minute runtime, as Pedigo is steadfast in his voiceless ways. It’s cinematic in the way that it makes you feel something that is so often indescribable yet beautiful. You can picture each track unfolding like a climactic scene or an expositional montage, and that’s what makes Pedigo’s music so accessible—because the sounds themselves can be interpreted and loved differently by anyone. “Signal of Hope” has a pedal steel in it that sounds like something Led Zeppelin cooked up on “Tangerine,” while “Nearer, Nearer” has a back porch singalong-like innocence to it. There’s a vast prairie beyond these melodies; a spectrum of technicolor still turning bright. At seven concise tracks, the stories feel unique and familiar all at the same time. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Hayden Pedigo’s latest album, The Happiest Times I Ever Ignored, arrives beautiful and damning in its vulnerability—all without a single word uttered across the record’s 37-minute runtime, as Pedigo is steadfast in his voiceless ways. It’s cinematic in the way that it makes you feel something that is so often indescribable yet beautiful. You can picture each track unfolding like a climactic scene or an expositional montage, and that’s what makes Pedigo’s music so accessible—because the sounds themselves can be interpreted and loved differently by anyone. “Signal of Hope” has a pedal steel in it that sounds like something Led Zeppelin cooked up on “Tangerine,” while “Nearer, Nearer” has a back porch singalong-like innocence to it. There’s a vast prairie beyond these melodies; a spectrum of technicolor still turning bright. At seven concise tracks, the stories feel unique and familiar all at the same time. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The sonic quality of Every Acre burrows deeper into the warm nest that McEntire and her band created on 2020’s Eno Axis. With minimal arrangements, McEntire and her small circle of musicians—which includes guitarist Luke Norton, bassist Casey Toll and drummer Daniel Faust—never rush or overwhelm with complexity. Instead, McEntire and Norton’s warm and often tremolo guitars hum and converse with Toll and Faust’s laidback southern swing. The production by Miss Thangs, McEntire and Norton captures these performances with the delicacy of a paranormal investigator trying not to disturb spirits coaxed into revealing their hidden forms. It’s not necessarily a low-key album, as certain songs build with the ferocity of Neil Young’s Crazy Horse or even the dead-of-winter acidic guitar heroics of Jeff Tweedy during Wilco’s A Ghost is Born era. Songs like “Turpentine” and “Soft Crook” provide the right amount of stomp underneath McEntire’s expressive vocals and Norton’s blistering leads. On the former, McEntire is assisted by Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls and lays out these questions surrounding the cruelty of land ownership. “Every acre that you ever owned / Hissed and split like a radiator hose,” she sings at one moment, acknowledging the faulty concept. “Hallelujah, turpentine! We can tend the land for a little while / Bones of those beneath the boundary lines—East in sets first / then clockwise, clockwise.” McEntire does not always spell out her feelings in bold fonts, as these connections are revealed and appreciated more with deep and repeated listens. And that’s the beauty of her music in a nutshell. With her commanding and achingly beautiful voice, you can easily miss the subtleties of her writing being swept away by the grandeur of her presentation. —Pat King

The sonic quality of Every Acre burrows deeper into the warm nest that McEntire and her band created on 2020’s Eno Axis. With minimal arrangements, McEntire and her small circle of musicians—which includes guitarist Luke Norton, bassist Casey Toll and drummer Daniel Faust—never rush or overwhelm with complexity. Instead, McEntire and Norton’s warm and often tremolo guitars hum and converse with Toll and Faust’s laidback southern swing. The production by Miss Thangs, McEntire and Norton captures these performances with the delicacy of a paranormal investigator trying not to disturb spirits coaxed into revealing their hidden forms. It’s not necessarily a low-key album, as certain songs build with the ferocity of Neil Young’s Crazy Horse or even the dead-of-winter acidic guitar heroics of Jeff Tweedy during Wilco’s A Ghost is Born era. Songs like “Turpentine” and “Soft Crook” provide the right amount of stomp underneath McEntire’s expressive vocals and Norton’s blistering leads. On the former, McEntire is assisted by Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls and lays out these questions surrounding the cruelty of land ownership. “Every acre that you ever owned / Hissed and split like a radiator hose,” she sings at one moment, acknowledging the faulty concept. “Hallelujah, turpentine! We can tend the land for a little while / Bones of those beneath the boundary lines—East in sets first / then clockwise, clockwise.” McEntire does not always spell out her feelings in bold fonts, as these connections are revealed and appreciated more with deep and repeated listens. And that’s the beauty of her music in a nutshell. With her commanding and achingly beautiful voice, you can easily miss the subtleties of her writing being swept away by the grandeur of her presentation. —Pat King San Francisco singer/songwriter Indianna Hale’s new LP,

San Francisco singer/songwriter Indianna Hale’s new LP,  Weathervanes is another undeniable offering from Isbell and his fellow 400 Unit players—who, together, constitute one of the best live rock bands on the road at any given time. Like Isbell’s solo magnum opus Southeastern, Weathervanes hits close to home, but it finds more inspiration in the everyday moments. While the album is more of a straight trail than a winding path with lots of peaks and valleys, its steadiness is one of its most attractive attributes. Within the first 20 seconds of the album, Isbell sings: “Everybody dies but you’ve gotta find a reason to carry on.” And while the 400 Unit frequently excels at rocking out (just listen to the entirety of “Miles” and the heartbreaker “When We Were Close” for proof), some of Isbell’s best work is found in his folk songs. He reminds us some of the best wisdom comes from questioning the status quo on the harmonica-infused “Cast Iron Skillet” and encapsulates the phenomenon of just wishing you could step out of your own life for a minute on “Volunteer.” —Ellen Johnson [

Weathervanes is another undeniable offering from Isbell and his fellow 400 Unit players—who, together, constitute one of the best live rock bands on the road at any given time. Like Isbell’s solo magnum opus Southeastern, Weathervanes hits close to home, but it finds more inspiration in the everyday moments. While the album is more of a straight trail than a winding path with lots of peaks and valleys, its steadiness is one of its most attractive attributes. Within the first 20 seconds of the album, Isbell sings: “Everybody dies but you’ve gotta find a reason to carry on.” And while the 400 Unit frequently excels at rocking out (just listen to the entirety of “Miles” and the heartbreaker “When We Were Close” for proof), some of Isbell’s best work is found in his folk songs. He reminds us some of the best wisdom comes from questioning the status quo on the harmonica-infused “Cast Iron Skillet” and encapsulates the phenomenon of just wishing you could step out of your own life for a minute on “Volunteer.” —Ellen Johnson [ Time Ain’t Accidental arrives like a rebirth for Jess Williamson. The centerpiece narrative of the album is a breakup—which she went through during the early throes of COVID—paired with a liberated sense of self-reflection and new musical headspace. One of Williamson’s greatest strengths is her ability to captivate a room without yelling too loud to grab everyone’s attention. It’s through her vocals—which are as angelic as they are familiar, alive and airy—that move the compass’ needle on her albums, and they shine so deftly on “Hunter,” “Chasing Spirits” and “Roads.” There’s empowerment far and wide across Time Ain’t Accidental, as if Williamson emerged on the other side of transitional grief with a new lease on autonomy, gratitude and kindness. But that didn’t come without her own personal carnage, which she presents to us in some of country music’s richest and most-animated vignettes. —Matt Mitchell [

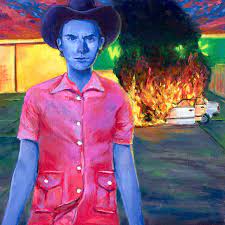

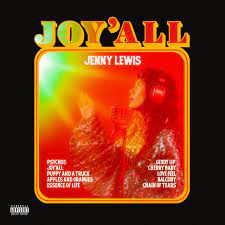

Time Ain’t Accidental arrives like a rebirth for Jess Williamson. The centerpiece narrative of the album is a breakup—which she went through during the early throes of COVID—paired with a liberated sense of self-reflection and new musical headspace. One of Williamson’s greatest strengths is her ability to captivate a room without yelling too loud to grab everyone’s attention. It’s through her vocals—which are as angelic as they are familiar, alive and airy—that move the compass’ needle on her albums, and they shine so deftly on “Hunter,” “Chasing Spirits” and “Roads.” There’s empowerment far and wide across Time Ain’t Accidental, as if Williamson emerged on the other side of transitional grief with a new lease on autonomy, gratitude and kindness. But that didn’t come without her own personal carnage, which she presents to us in some of country music’s richest and most-animated vignettes. —Matt Mitchell [ Despite the planetary clusterfuck it was largely written in, Joy’All is Lewis’ brightest, grooviest and coolest album yet. The 10 tracks live up to the title they’re packaged under. Even “Balcony,” which she wrote as a tribute to a friend who died by suicide during lockdown, evokes a celebratory memorial rather than a solemn eulogy. This new chapter finds Lewis shifting the perspectives from other people onto herself, and it’s done so with a generosity that feels both earned and quantifiable. In the wake of the pandemic, there’s been no shortage of poppy records getting releases from indie artists. Lewis herself is mining through a bend of honky-tonk, psych-rock and disco on Joy’All. While the album is not as lyrically dense as On the Line was four years ago, it does, in many ways, outshine its predecessor compositionally. Lewis opts to not take herself so seriously, even if she’s mining through the last gasps of recent, unresolved trauma. And that alone is a testament to her genius, as it’s infinitely harder to write through joy than it is agony. —Matt Mitchell [

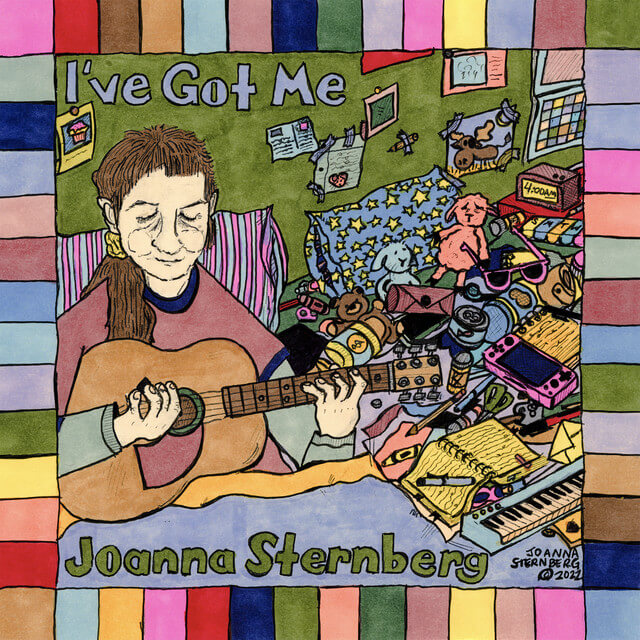

Despite the planetary clusterfuck it was largely written in, Joy’All is Lewis’ brightest, grooviest and coolest album yet. The 10 tracks live up to the title they’re packaged under. Even “Balcony,” which she wrote as a tribute to a friend who died by suicide during lockdown, evokes a celebratory memorial rather than a solemn eulogy. This new chapter finds Lewis shifting the perspectives from other people onto herself, and it’s done so with a generosity that feels both earned and quantifiable. In the wake of the pandemic, there’s been no shortage of poppy records getting releases from indie artists. Lewis herself is mining through a bend of honky-tonk, psych-rock and disco on Joy’All. While the album is not as lyrically dense as On the Line was four years ago, it does, in many ways, outshine its predecessor compositionally. Lewis opts to not take herself so seriously, even if she’s mining through the last gasps of recent, unresolved trauma. And that alone is a testament to her genius, as it’s infinitely harder to write through joy than it is agony. —Matt Mitchell [ The songs on I’ve Got Me start simply, then bloom into playful complexity. The title track builds off of the themes of Then I Try Some More, exploring the ways that a commitment to growth can mask self-destruction. “I’ve Got Me” almost starts off as a pep talk before the edge creeps in, with Sternberg picking behind a sing-songy “all my faults and flaws and lies are no one’s fault but mine.” But where “This is Not Who I Want to Be” went external two years ago, hoping for another person to come along and force a change, “I’ve Got Me” dreams of breaking out of these patterns. It’s a struggle that continues throughout the album, as Sternberg tracks a dogged healing process through twelve deeply reflective tracks. The tracks on I’ve Got Me seem to go back and forth in their relationship to turmoil, but this shouldn’t be taken as disorganization. Rather, the album’s ordering feels acutely intentional: Grief is nonlinear, as is healing. —Annie Parnell

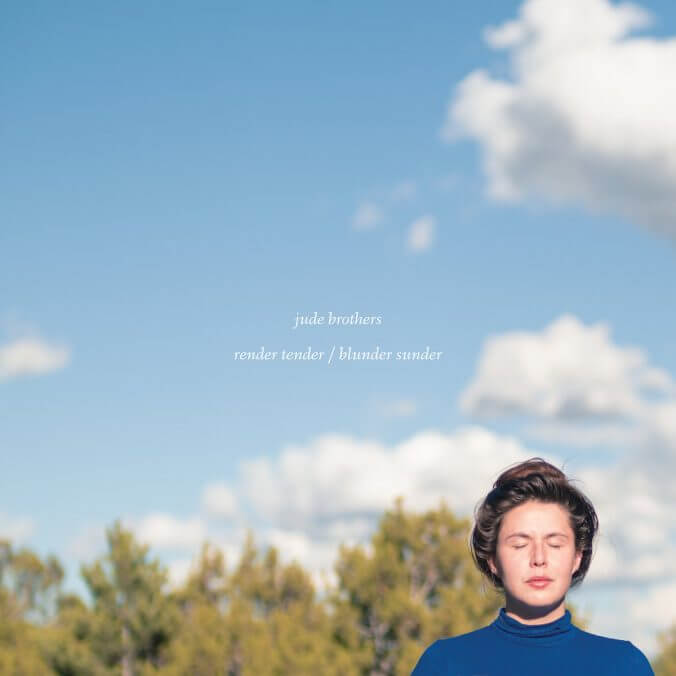

The songs on I’ve Got Me start simply, then bloom into playful complexity. The title track builds off of the themes of Then I Try Some More, exploring the ways that a commitment to growth can mask self-destruction. “I’ve Got Me” almost starts off as a pep talk before the edge creeps in, with Sternberg picking behind a sing-songy “all my faults and flaws and lies are no one’s fault but mine.” But where “This is Not Who I Want to Be” went external two years ago, hoping for another person to come along and force a change, “I’ve Got Me” dreams of breaking out of these patterns. It’s a struggle that continues throughout the album, as Sternberg tracks a dogged healing process through twelve deeply reflective tracks. The tracks on I’ve Got Me seem to go back and forth in their relationship to turmoil, but this shouldn’t be taken as disorganization. Rather, the album’s ordering feels acutely intentional: Grief is nonlinear, as is healing. —Annie Parnell The sophomore full-length from Santa Fe Celtic lever harpist Jude Brothers is a sight to behold. All at once, the record merges threadbare singer/songwriter folk framework with string-forward melancholia. Brothers makes good use of their vast compositional talents, navigating grief and heartbreak through the always expanding doorways of loss. Songs like “Yar Wut Yar / I Love You for It!” and “Practicing Silence / Looking for Water!” establish just how free-form and surrendering Brothers’ work is, as they mine through the bizarre and the poetic to hone in their own visceral vision and unparalleled voice—the latter of which is Brothers’ greatest asset, their singing erupting through every arrangement like a profound, Joanna Newsom-conjuring, brilliant siren. Render Tender / Blunder Sunder is, at times, beyond articulation. It’s so deftly woven into the American Folk Songbook that the beautiful convergence of traditional song structure and off-the-beaten-path beauty is sometimes indecipherable. The album is a mark of unique, mystifying singularity. —Matt Mitchell

The sophomore full-length from Santa Fe Celtic lever harpist Jude Brothers is a sight to behold. All at once, the record merges threadbare singer/songwriter folk framework with string-forward melancholia. Brothers makes good use of their vast compositional talents, navigating grief and heartbreak through the always expanding doorways of loss. Songs like “Yar Wut Yar / I Love You for It!” and “Practicing Silence / Looking for Water!” establish just how free-form and surrendering Brothers’ work is, as they mine through the bizarre and the poetic to hone in their own visceral vision and unparalleled voice—the latter of which is Brothers’ greatest asset, their singing erupting through every arrangement like a profound, Joanna Newsom-conjuring, brilliant siren. Render Tender / Blunder Sunder is, at times, beyond articulation. It’s so deftly woven into the American Folk Songbook that the beautiful convergence of traditional song structure and off-the-beaten-path beauty is sometimes indecipherable. The album is a mark of unique, mystifying singularity. —Matt Mitchell What the Chicago-based interdisciplinary writer and musician Kara Jackson accomplishes on her debut LP Why Does The Earth Give Us People To Love is not “raw,” at least not in the sense that the writing is unrefined or off-the-cuff. Instead, that distinction comes through how the listener is made to feel listening to Jackson’s cosmic country jams. Lines like “Some people take lives to be recognized” are delivered with nonchalance, and the way she belts “don’t you bother me” over swirling harp notes elicits chills. Jackson is communicating her message with precise orchestration for optimal impact. As a listener, you may feel exposed, maybe even singled out. Jackson starts the album with “recognized,” a lo-fi exercise contemplating what people do for validation and why. As she and her piano arpeggiate, she raises the stakes. It contrasts with the lush “no fun/party,” where her theatrical voice balances with a racing guitar and reclining strings. She reckons with men who won’t rise to the occasion and take that out on her and, as much as she laments the loss of companionship, she remembers that the other person is just as liable to miss her, too. Across the album, Jackson’s expert guitar work and lyricism reveals an extensive archive of her relationships with peers, partners and more who she’s entrusted with her love. Many of those people are men who’ve mishandled that love. When Jackson is solo, she is a force. With her friends’ help, the result is divine. —Devon Chodzin

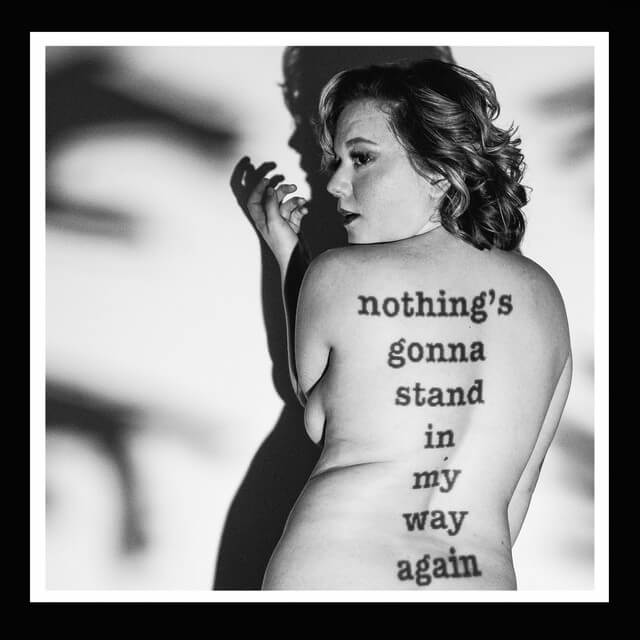

What the Chicago-based interdisciplinary writer and musician Kara Jackson accomplishes on her debut LP Why Does The Earth Give Us People To Love is not “raw,” at least not in the sense that the writing is unrefined or off-the-cuff. Instead, that distinction comes through how the listener is made to feel listening to Jackson’s cosmic country jams. Lines like “Some people take lives to be recognized” are delivered with nonchalance, and the way she belts “don’t you bother me” over swirling harp notes elicits chills. Jackson is communicating her message with precise orchestration for optimal impact. As a listener, you may feel exposed, maybe even singled out. Jackson starts the album with “recognized,” a lo-fi exercise contemplating what people do for validation and why. As she and her piano arpeggiate, she raises the stakes. It contrasts with the lush “no fun/party,” where her theatrical voice balances with a racing guitar and reclining strings. She reckons with men who won’t rise to the occasion and take that out on her and, as much as she laments the loss of companionship, she remembers that the other person is just as liable to miss her, too. Across the album, Jackson’s expert guitar work and lyricism reveals an extensive archive of her relationships with peers, partners and more who she’s entrusted with her love. Many of those people are men who’ve mishandled that love. When Jackson is solo, she is a force. With her friends’ help, the result is divine. —Devon Chodzin Loveless has learned a few things since Indestructible Machine, many of which inform the singer’s latest album. Nothing’s Gonna Stand in My Way Again shows how they have become more thoughtful as a songwriter. She could always write a hook—see “Learn to Say No,” among plenty of other earlier tunes—but Loveless now is a smarter, subtler lyricist who hasn’t lost any of the candor that made her so compelling in the first place. On the new album, their fifth full-length, they apply those skills to 10 songs featuring searing self-assessments, but also a measure of compassion that wasn’t always there in the past. These songs stem from the isolation Loveless felt during the pandemic, the anguish caused by a breakup in the middle of all that and a return to Columbus after a stretch living in North Carolina. Accordingly, Nothing’s Gonna Stand in My Way Again reflects a sense of starting over, combined with the resilience and determination of a performer who’s been forging a path basically since the start (or at least since Loveless created some distance between themselves and their overly slick 2010 album, The Only Man, which came out when they were 19). It’s not just what Loveless sings on these tracks, but how they sing it. The musical palette here is more expansive than the flame-thrower alt-country of Loveless’ earlier work, and they use their voice in a way that complements the song rather than dominating it. —Eric R. Danton [

Loveless has learned a few things since Indestructible Machine, many of which inform the singer’s latest album. Nothing’s Gonna Stand in My Way Again shows how they have become more thoughtful as a songwriter. She could always write a hook—see “Learn to Say No,” among plenty of other earlier tunes—but Loveless now is a smarter, subtler lyricist who hasn’t lost any of the candor that made her so compelling in the first place. On the new album, their fifth full-length, they apply those skills to 10 songs featuring searing self-assessments, but also a measure of compassion that wasn’t always there in the past. These songs stem from the isolation Loveless felt during the pandemic, the anguish caused by a breakup in the middle of all that and a return to Columbus after a stretch living in North Carolina. Accordingly, Nothing’s Gonna Stand in My Way Again reflects a sense of starting over, combined with the resilience and determination of a performer who’s been forging a path basically since the start (or at least since Loveless created some distance between themselves and their overly slick 2010 album, The Only Man, which came out when they were 19). It’s not just what Loveless sings on these tracks, but how they sing it. The musical palette here is more expansive than the flame-thrower alt-country of Loveless’ earlier work, and they use their voice in a way that complements the song rather than dominating it. —Eric R. Danton [ Margo Cilker’s approach to construction transcends reference. I’m transported to someplace familiar, though I cannot begin to say where, exactly. The Washington-via-California musician put out her debut album Pohorylle just two years ago; but, on Valley Of Heart’s Delight, it sounds like she’s got a century’s worth of stories to tell. To segue from “Lowland Trail” into “Keep It On A Burner” is a huge flex on Cilker’s part. Here, she takes a beautiful country musing and turns it into this gigantic, rewarding soundscape set adrift with Kelly Pratt’s horns and Jenny Conlee-Drizos’ crystalline piano. What’s, maybe, most remarkable about Valley Of Heart’s Delight is how unabashed it is about adopting the tradition of country music while also, simultaneously, chiding the very concept of embracing such a silly history. Twang is not a vessel to step into for Cilker, it’s a way of life that surrounds her every beating step. Through lessons taken from the songbooks of John Prine and Gillian Welch, there are inflections of gospel, cowboy chords, soft rock and Americana running through the veins of each track. And, at no point on this album does Cilker ever waver in her convictions, her own prophecies or her own pace towards finding the righteousness she greatly wants—all of which feel so deftly urgent and necessary. —Matt Mitchell

Margo Cilker’s approach to construction transcends reference. I’m transported to someplace familiar, though I cannot begin to say where, exactly. The Washington-via-California musician put out her debut album Pohorylle just two years ago; but, on Valley Of Heart’s Delight, it sounds like she’s got a century’s worth of stories to tell. To segue from “Lowland Trail” into “Keep It On A Burner” is a huge flex on Cilker’s part. Here, she takes a beautiful country musing and turns it into this gigantic, rewarding soundscape set adrift with Kelly Pratt’s horns and Jenny Conlee-Drizos’ crystalline piano. What’s, maybe, most remarkable about Valley Of Heart’s Delight is how unabashed it is about adopting the tradition of country music while also, simultaneously, chiding the very concept of embracing such a silly history. Twang is not a vessel to step into for Cilker, it’s a way of life that surrounds her every beating step. Through lessons taken from the songbooks of John Prine and Gillian Welch, there are inflections of gospel, cowboy chords, soft rock and Americana running through the veins of each track. And, at no point on this album does Cilker ever waver in her convictions, her own prophecies or her own pace towards finding the righteousness she greatly wants—all of which feel so deftly urgent and necessary. —Matt Mitchell The follow-up to 2020’s electric That’s How Rumors Get Started, Strays honors Price’s beginnings in American roots music while painting a psych-rock backdrop to her stories of redemption, survival and rebirth. The result is familiar—it’s undeniably a Margo Price record—but a little extra fiery. Of course, Strays never veers too far from country music, which is intrinsically wrapped up in rock ’n’ roll anyways. The devastating “County Road” and ode to lovemaking “Light Me Up” wouldn’t sound out of place on a proper country record. But Price also specializes in psychedelia, which can be heard from the reverberations of “Been To The Mountain” to the greasy, spaced-out vocals on “Change Of Heart” to the twangy echoes on the ominous “Hell In The Heartland.” Some songs are fueled by Price’s folk beginnings, including protest single “Lydia,” which is a sprawling scene not unlike the album closer and title track from 2017’s All American Made. Protest music has taken many shapes over the course of America’s history, but folk music will always be a fitting framework, and it’s one Price understands beautifully. Actually written before Roe v. Wade was overturned, the drug-laced “Lydia” is a fiction following a woman strapped with an impossible decision. It’s just further proof of Price’s gift for not only telling her own powerful stories, but also those of the downtrodden en masse. The songs on Strays can appear like a mirror, or like a biography, or like a string of character studies—a sure sign of good songwriting. —Ellen Johnson [

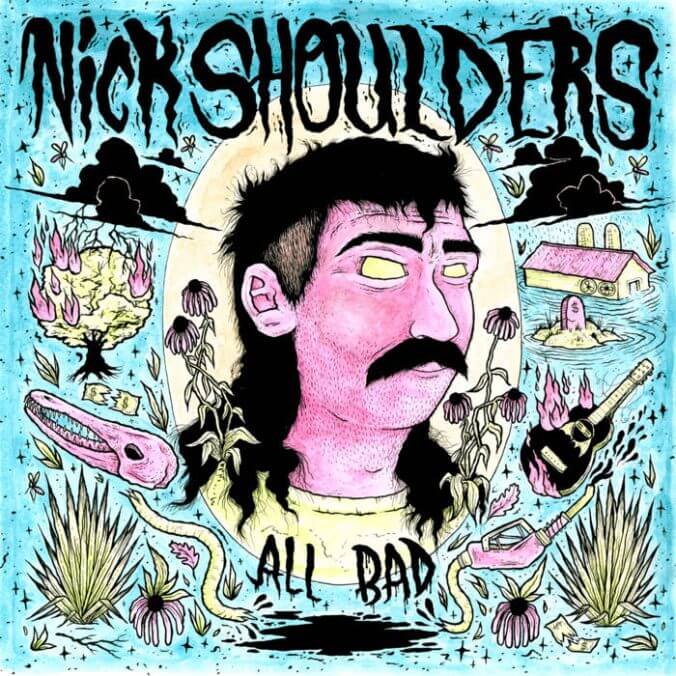

The follow-up to 2020’s electric That’s How Rumors Get Started, Strays honors Price’s beginnings in American roots music while painting a psych-rock backdrop to her stories of redemption, survival and rebirth. The result is familiar—it’s undeniably a Margo Price record—but a little extra fiery. Of course, Strays never veers too far from country music, which is intrinsically wrapped up in rock ’n’ roll anyways. The devastating “County Road” and ode to lovemaking “Light Me Up” wouldn’t sound out of place on a proper country record. But Price also specializes in psychedelia, which can be heard from the reverberations of “Been To The Mountain” to the greasy, spaced-out vocals on “Change Of Heart” to the twangy echoes on the ominous “Hell In The Heartland.” Some songs are fueled by Price’s folk beginnings, including protest single “Lydia,” which is a sprawling scene not unlike the album closer and title track from 2017’s All American Made. Protest music has taken many shapes over the course of America’s history, but folk music will always be a fitting framework, and it’s one Price understands beautifully. Actually written before Roe v. Wade was overturned, the drug-laced “Lydia” is a fiction following a woman strapped with an impossible decision. It’s just further proof of Price’s gift for not only telling her own powerful stories, but also those of the downtrodden en masse. The songs on Strays can appear like a mirror, or like a biography, or like a string of character studies—a sure sign of good songwriting. —Ellen Johnson [ On All Bad, Nick Shoulders documents the backyards and rolling hills and rivers he calls home—and how those glimmers of natural hope and grace are being suppressed in the name of underpaid, exhausted labor and the cost of living skyrocketing in towns of mere thousands. “There once was land, endless land, under starry skies above, but they fenced us in,” Shoulders sings on “Won’t Fence Us In.” “Now it’s interstates and interchanges, monocrop and truck stops, ‘cause they fenced us in! I wish that every golf course became a WMA and every politician knew the rent that we paid, just to drink ourselves to death and go to jobs that we hate.” Across renderings of November hurricanes, acid rain, plateau hollows and cul-de-sacs craving rust, Shoulders dares to outmuscle his and his peers’ propensities for letting the well-built cage of their eroding hometowns keep them locked away. There’s an exploration of a certain, generous dichotomy that Shoulders enacts flawlessly. Seeing disparities and balancing them with depictions of the natural wonders that still, in some places, exist in the Ozarks and the Bayou is something that is reflective of the contradicting brutality that sits before Shoulders on a daily basis when he’s back home. It’s a deft, intimate and complicated portrait of the South and beyond. —Matt Mitchell [

On All Bad, Nick Shoulders documents the backyards and rolling hills and rivers he calls home—and how those glimmers of natural hope and grace are being suppressed in the name of underpaid, exhausted labor and the cost of living skyrocketing in towns of mere thousands. “There once was land, endless land, under starry skies above, but they fenced us in,” Shoulders sings on “Won’t Fence Us In.” “Now it’s interstates and interchanges, monocrop and truck stops, ‘cause they fenced us in! I wish that every golf course became a WMA and every politician knew the rent that we paid, just to drink ourselves to death and go to jobs that we hate.” Across renderings of November hurricanes, acid rain, plateau hollows and cul-de-sacs craving rust, Shoulders dares to outmuscle his and his peers’ propensities for letting the well-built cage of their eroding hometowns keep them locked away. There’s an exploration of a certain, generous dichotomy that Shoulders enacts flawlessly. Seeing disparities and balancing them with depictions of the natural wonders that still, in some places, exist in the Ozarks and the Bayou is something that is reflective of the contradicting brutality that sits before Shoulders on a daily basis when he’s back home. It’s a deft, intimate and complicated portrait of the South and beyond. —Matt Mitchell [ With the line “My god, it’s good to see you,” Nickel Creek welcomes you back after nine years with Celebrants, their first original album since 2014’s A Dotted Line, and quickly acknowledges that we have work to do. The trio, composed of Chris Thile, Sean Watkins and Sara Watkins, and joined by Mike Elizondo, has been making Americana music together in ebbs and flows for more than 20 years. By now, they know something about working together. What might lie ahead is “something we can sing through”—having incisively clever-sounding harmonies like theirs certainly helps. The group rapidly weaves together and apart on this album, from the tearing pace of Thile’s mandolin or Sara Watkins’s fiddle to the quick wit of their lyrics. There is patience for moments of rest and quiet, but they do not suffer inactivity. The music demands an awareness of movement—“Celebrants” has literal stomping, whereas on “Strangers” the instrumentation takes on the sureness of footsteps, whether through the dancing lightness of Thile’s mandolin, or the certain stepping of Mike Elizondo’s bass. The mix of instrumental tracks with vocals reminds us that more than anything, Nickel Creek are avid musicians, full of feeling accented by their technical prowess. Sara Watkins’s jazz-inflected vocal slides on “Thinnest Wall” are made all the more exhilarating by their unexpectedness, mischievously playing with their usual bluegrass sound. At the heart of this album is a feeling of running a losing race, with words of panic and love jumbling together until you can’t separate the notions anymore. To love anything or anyone right now is to agree to go through a period of immense change and dread together, and to risk losing each other. You have to choose your partners in forging ahead carefully, and Nickel Creek is more locked in and together than ever. —Rosa Sofia Kaminski

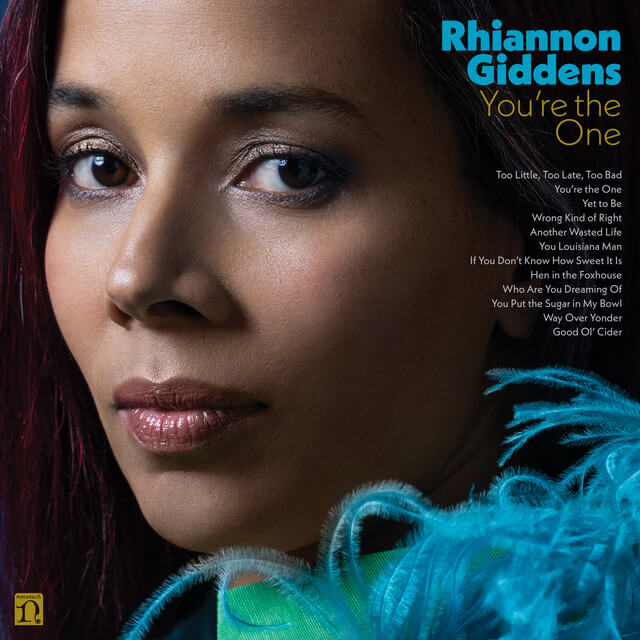

With the line “My god, it’s good to see you,” Nickel Creek welcomes you back after nine years with Celebrants, their first original album since 2014’s A Dotted Line, and quickly acknowledges that we have work to do. The trio, composed of Chris Thile, Sean Watkins and Sara Watkins, and joined by Mike Elizondo, has been making Americana music together in ebbs and flows for more than 20 years. By now, they know something about working together. What might lie ahead is “something we can sing through”—having incisively clever-sounding harmonies like theirs certainly helps. The group rapidly weaves together and apart on this album, from the tearing pace of Thile’s mandolin or Sara Watkins’s fiddle to the quick wit of their lyrics. There is patience for moments of rest and quiet, but they do not suffer inactivity. The music demands an awareness of movement—“Celebrants” has literal stomping, whereas on “Strangers” the instrumentation takes on the sureness of footsteps, whether through the dancing lightness of Thile’s mandolin, or the certain stepping of Mike Elizondo’s bass. The mix of instrumental tracks with vocals reminds us that more than anything, Nickel Creek are avid musicians, full of feeling accented by their technical prowess. Sara Watkins’s jazz-inflected vocal slides on “Thinnest Wall” are made all the more exhilarating by their unexpectedness, mischievously playing with their usual bluegrass sound. At the heart of this album is a feeling of running a losing race, with words of panic and love jumbling together until you can’t separate the notions anymore. To love anything or anyone right now is to agree to go through a period of immense change and dread together, and to risk losing each other. You have to choose your partners in forging ahead carefully, and Nickel Creek is more locked in and together than ever. —Rosa Sofia Kaminski A MacArthur Fellow, Rhiannon Giddens has always been a skilled investigator—finding paths toward examining the past and her own emotions in tandem with equal commitment, grace and gravitas. She often pairs storytelling with a careful selection of instruments—punctuated by her studied understanding of those instruments’ interwoven histories. Her albums with Turrisi—one of many longtime collaborators who also worked on You’re the One, along with Dirk Powell, Jason Syphe and Niwel Tsumbu—incorporated her ability to bring startling new narrative implications to longstanding classics, through revelatory takes on songs like “Amazing Grace” and “Wayfaring Stranger.” Her love of storytelling is clear in her prior projects—but also her assertion that storytelling is a matter of power. In an interview about Omar, Giddens referenced the type of harm she often strives to counteract in her work: “Our history is not being told to us.” Her musical ventures have often been driven by thoughtful exploration, research and the ability to unearth linkages between traditions that span across centuries and geographies. These formidable capabilities are sometimes balanced by playfulness, and always elevated by Giddens’s willingness to commit to the fullest level of emotional expression to help her channel her songs in the way she intends.You’re the One shares these abilities, but finds pure emotion unfolding at the forefront. It’s a deeply fun album that beckons the listener’s attention immediately. Right away, Giddens bids good riddance to anything not serving her, swearing off a lover who’d taken her for granted in the declarative, R&B-styled “Too Little, Too Late, Too Bad.” This and the second track, the titular “You’re the One,” inspired by her love for her children, provide a kind of twinned introduction to some of the emotional drivers of this record: casting aside those whose perspectives are no longer informative to Giddens, and looking to the future by way of the present. —Laura Dzubay

A MacArthur Fellow, Rhiannon Giddens has always been a skilled investigator—finding paths toward examining the past and her own emotions in tandem with equal commitment, grace and gravitas. She often pairs storytelling with a careful selection of instruments—punctuated by her studied understanding of those instruments’ interwoven histories. Her albums with Turrisi—one of many longtime collaborators who also worked on You’re the One, along with Dirk Powell, Jason Syphe and Niwel Tsumbu—incorporated her ability to bring startling new narrative implications to longstanding classics, through revelatory takes on songs like “Amazing Grace” and “Wayfaring Stranger.” Her love of storytelling is clear in her prior projects—but also her assertion that storytelling is a matter of power. In an interview about Omar, Giddens referenced the type of harm she often strives to counteract in her work: “Our history is not being told to us.” Her musical ventures have often been driven by thoughtful exploration, research and the ability to unearth linkages between traditions that span across centuries and geographies. These formidable capabilities are sometimes balanced by playfulness, and always elevated by Giddens’s willingness to commit to the fullest level of emotional expression to help her channel her songs in the way she intends.You’re the One shares these abilities, but finds pure emotion unfolding at the forefront. It’s a deeply fun album that beckons the listener’s attention immediately. Right away, Giddens bids good riddance to anything not serving her, swearing off a lover who’d taken her for granted in the declarative, R&B-styled “Too Little, Too Late, Too Bad.” This and the second track, the titular “You’re the One,” inspired by her love for her children, provide a kind of twinned introduction to some of the emotional drivers of this record: casting aside those whose perspectives are no longer informative to Giddens, and looking to the future by way of the present. —Laura Dzubay On Crying, Laughing, Waving, Smiling, Slaughter Beach, Dog start on the outside of something and doesn’t really try to get inside—instead, they meander around out there, seeing what they can find and, from time to time, peering in through the glass. The first single—and the album’s second track—“Strange Weather,” sets up this seeking early. “How am I still unsure?” Ewald questions, across an upbeat arrangement laced with rounds of percussion and scratchy, quietly moody guitar instrumentation reminiscent of Abbey Road-era Beatles. There’s a sense of drifting across the album, a soft indie-rock escapade through city streets, small towns and diners. The songs are full of Americana imagery and richly detailed scenes vivid enough to take in—and taking them in feels incredibly easy when the music has such a gliding, soaring quality. “Engine” is one of the clearest examples—an easygoing but troubled odyssey through the desert, the woods, bars and a family reunion—as it boasts such an even-keeled rhythm of soft taps and drum beats, so much so that you might not even notice that it’s nearly nine minutes long. A confession, “The truth is I live to roll over,” tips the second half of the song into a long, brooding instrumental—mirroring the first four minutes in effect but with more friction seeping into prolonged electric guitar riffs. Across these songs, love is something felt through someone’s presence next to you: reading a sign, their hand on a drink next to your own. That’s what these lovers and characters are maybe feeling, and that’s the wordlessness these songs offer: a quick spotlight of how simple it looks, watching them watching the big wheel. —Laura Dzubay [Read our full feature]

On Crying, Laughing, Waving, Smiling, Slaughter Beach, Dog start on the outside of something and doesn’t really try to get inside—instead, they meander around out there, seeing what they can find and, from time to time, peering in through the glass. The first single—and the album’s second track—“Strange Weather,” sets up this seeking early. “How am I still unsure?” Ewald questions, across an upbeat arrangement laced with rounds of percussion and scratchy, quietly moody guitar instrumentation reminiscent of Abbey Road-era Beatles. There’s a sense of drifting across the album, a soft indie-rock escapade through city streets, small towns and diners. The songs are full of Americana imagery and richly detailed scenes vivid enough to take in—and taking them in feels incredibly easy when the music has such a gliding, soaring quality. “Engine” is one of the clearest examples—an easygoing but troubled odyssey through the desert, the woods, bars and a family reunion—as it boasts such an even-keeled rhythm of soft taps and drum beats, so much so that you might not even notice that it’s nearly nine minutes long. A confession, “The truth is I live to roll over,” tips the second half of the song into a long, brooding instrumental—mirroring the first four minutes in effect but with more friction seeping into prolonged electric guitar riffs. Across these songs, love is something felt through someone’s presence next to you: reading a sign, their hand on a drink next to your own. That’s what these lovers and characters are maybe feeling, and that’s the wordlessness these songs offer: a quick spotlight of how simple it looks, watching them watching the big wheel. —Laura Dzubay [Read our full feature] A deeply stirring and infectious collection of alt-folk tracks, Sunny War’s latest album Anarchist Gospel aims to navigate the contradictory forces of spirituality and violence through unfiltered, brilliant vignettes that pair flickers of blues, gospel, cowboy chords and punk rock. While the immense heaviness of the surrounding world feels extra worrisome at times, Anarchist Gospel is packed to the brim with messages of hope. “No Reason” is the record’s centerpiece, as Sunny War makes good use of blitzkrieg riffs and nuanced storytelling. “The ones you love most, you upset,” she sings. “You haven’t got forgiveness yet.” Elsewhere, “Whole” and “New Day” are her dusty, conflicted ruminations on self-destruction and the malleability of humanity and our collective yearning for resilience. Sunny War’s fourth album is not just her best, it’s her most urgent. —Matt Mitchell

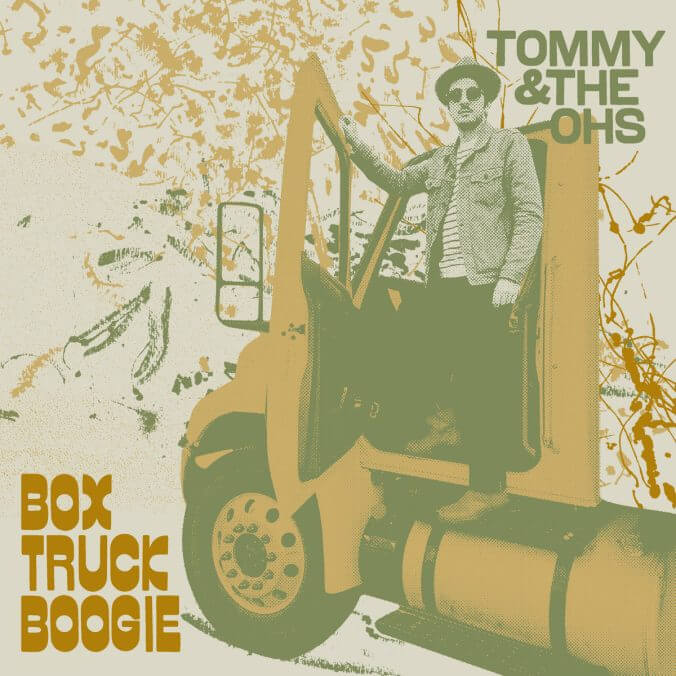

A deeply stirring and infectious collection of alt-folk tracks, Sunny War’s latest album Anarchist Gospel aims to navigate the contradictory forces of spirituality and violence through unfiltered, brilliant vignettes that pair flickers of blues, gospel, cowboy chords and punk rock. While the immense heaviness of the surrounding world feels extra worrisome at times, Anarchist Gospel is packed to the brim with messages of hope. “No Reason” is the record’s centerpiece, as Sunny War makes good use of blitzkrieg riffs and nuanced storytelling. “The ones you love most, you upset,” she sings. “You haven’t got forgiveness yet.” Elsewhere, “Whole” and “New Day” are her dusty, conflicted ruminations on self-destruction and the malleability of humanity and our collective yearning for resilience. Sunny War’s fourth album is not just her best, it’s her most urgent. —Matt Mitchell The latest effort from New Hope, Pennsylvania country group Tommy and the Ohs—an amalgam of Thomas Oliverio, Logan Oakley, Billy Contreras, Jimmy Rowland, Dave Harder, Justin Amaral, Cody Campbell, Adam Donald, Paul Thacker, Matt Meye, Ry Evans, Cecil Shields, Alicia Gail and Marlos E’Vian—is a staunchly wondrous collection of country tunes that arrive like a time capsule. Oliverio ushers us along, through songs like “On Yer Own,” “Reputation Tour” and “Pig on a Train,” and delivering sermons that sound like Michael Hurley covering David Berman songs (they do, after all, cover Silver Jews’ “Candy Jail”)—with an added touch of a waltzing boogie and cowboy chords. The work is earnest and damn catchy.

The latest effort from New Hope, Pennsylvania country group Tommy and the Ohs—an amalgam of Thomas Oliverio, Logan Oakley, Billy Contreras, Jimmy Rowland, Dave Harder, Justin Amaral, Cody Campbell, Adam Donald, Paul Thacker, Matt Meye, Ry Evans, Cecil Shields, Alicia Gail and Marlos E’Vian—is a staunchly wondrous collection of country tunes that arrive like a time capsule. Oliverio ushers us along, through songs like “On Yer Own,” “Reputation Tour” and “Pig on a Train,” and delivering sermons that sound like Michael Hurley covering David Berman songs (they do, after all, cover Silver Jews’ “Candy Jail”)—with an added touch of a waltzing boogie and cowboy chords. The work is earnest and damn catchy.  One of the most consistently hardworking folk singers in the world, Tré Burt returned this year with his first LP since 2021’s You, Yeah, You. Working as an integral piece of John Prine’s label—Oh Boy Records—roster, Burt takes a dip into the world of blues and funk and dance music on Traffic Fiction. The record is, in many ways, a soulful level-up from the singer/songwriter troubadour ethos of his previous albums. Burt is amassing one of the most vivid catalogs right now, one that is damn near uncategorical at this point. Just when you might expect him to continue leaning into the man-and-a-microphone work that’s become definitive of his oeuvre, he goes out and makes songs like “TOLD YA THEN” or “WIN MY HEART,” these striking assemblages of punctuated ambition and pure, unabridged talent and finesse. Tré Burt is for the people; Traffic Fiction is a record that demands to be played loud. —Matt Mitchell

One of the most consistently hardworking folk singers in the world, Tré Burt returned this year with his first LP since 2021’s You, Yeah, You. Working as an integral piece of John Prine’s label—Oh Boy Records—roster, Burt takes a dip into the world of blues and funk and dance music on Traffic Fiction. The record is, in many ways, a soulful level-up from the singer/songwriter troubadour ethos of his previous albums. Burt is amassing one of the most vivid catalogs right now, one that is damn near uncategorical at this point. Just when you might expect him to continue leaning into the man-and-a-microphone work that’s become definitive of his oeuvre, he goes out and makes songs like “TOLD YA THEN” or “WIN MY HEART,” these striking assemblages of punctuated ambition and pure, unabridged talent and finesse. Tré Burt is for the people; Traffic Fiction is a record that demands to be played loud. —Matt Mitchell At just seven songs and 28 minutes in length, Rustin’ In The Rain more closely resembles an EP than it does an album—even if it has been officially designated as the latter. But it would be unfair to dismiss Rustin’ In The Rain as a stopgap project sandwiched between more meaningful releases. Favoring a full-band sound over the scrappy homespun charm that defined some of Childers most iconic numbers in year’s past, like “Feathered Indians” and “Lady May,” this effort effectively showcases yet another dimension of the country innovator’s sound. Childers’ sixth album was led by the single “In Your Love”—a tasteful piano ballad which became his first entry on the Billboard Hot 100. The accompanying music video—depicting a romance between two coal miners (played by Colton Haynes and James Scully)—attracted media attention and a predictable response from homophobic trolls. Whereas other country artists reinforce the genre’s regressive, conservative reputation—be it by hurling racial slurs or scapegoating welfare recipients—Childers proves a thoughtful dissector of America and its past. His forward-thinking and inclusive vision for country music is evident in everything he does—his evocative world-building and the oft-ignored characters that populate said world invite people in rather than pit them against one another. For all of country music’s commercial success this past summer, many of the genre’s most popular songs right now resemble its past more than its future (or at least what one would hope constitutes its future). The music of Rustin’ In The Rain is an exception—and best of all, there’s space in its world for all of us. —Tom Williams

At just seven songs and 28 minutes in length, Rustin’ In The Rain more closely resembles an EP than it does an album—even if it has been officially designated as the latter. But it would be unfair to dismiss Rustin’ In The Rain as a stopgap project sandwiched between more meaningful releases. Favoring a full-band sound over the scrappy homespun charm that defined some of Childers most iconic numbers in year’s past, like “Feathered Indians” and “Lady May,” this effort effectively showcases yet another dimension of the country innovator’s sound. Childers’ sixth album was led by the single “In Your Love”—a tasteful piano ballad which became his first entry on the Billboard Hot 100. The accompanying music video—depicting a romance between two coal miners (played by Colton Haynes and James Scully)—attracted media attention and a predictable response from homophobic trolls. Whereas other country artists reinforce the genre’s regressive, conservative reputation—be it by hurling racial slurs or scapegoating welfare recipients—Childers proves a thoughtful dissector of America and its past. His forward-thinking and inclusive vision for country music is evident in everything he does—his evocative world-building and the oft-ignored characters that populate said world invite people in rather than pit them against one another. For all of country music’s commercial success this past summer, many of the genre’s most popular songs right now resemble its past more than its future (or at least what one would hope constitutes its future). The music of Rustin’ In The Rain is an exception—and best of all, there’s space in its world for all of us. —Tom Williams In comparison to the admirable (but intimidatingly long) American Heartbreak, Zach Bryan clocks in at a relatively concise 54 minutes. Though it traverses different tempos and altering emotional states, these 16 songs largely circle the same themes—the capacity of this world to corrupt us versus the forces that keep us going. “Overtime,” a propulsive anthem which begins with a “Star Spangled Banner” guitar lick, offers a litany of oppressive challenges (“a mean, mean gene in my family tree” and complaints about his “songs sound[ing] the same,” among them). A triumphant swirl of horns, guitars and drums imply what we already know: Bryan’s work is at a career, emotional high. Bryan mines the depth of grief across multiple moments on Zach Bryan—sometimes emerging with silver linings and suggestions of a better path forward, and sometimes not. The affecting “East Side of Sorrow” offers a strikingly precise (but widely relatable) tale that scales fighting a seemingly endless war, religious alienation and death. Amidst cascading tragedy, Bryan finds solace via expanding his horizons (“Stick out your chest, and then hit the road”) and offers a simple, but convincing, affirmation: “Let it be, then let it go”. Though Bryan spends his newest LP circling the same, reliable set of themes—love and its limitations, hopelessness and a deep well of resilience, etc.—you don’t emerge from the LP with a sense of linear narrative. Across 16 songs, relationships fail and prosper and then fail again; hope deteriorates and grows, only to deteriorate again. —Tom Williams

In comparison to the admirable (but intimidatingly long) American Heartbreak, Zach Bryan clocks in at a relatively concise 54 minutes. Though it traverses different tempos and altering emotional states, these 16 songs largely circle the same themes—the capacity of this world to corrupt us versus the forces that keep us going. “Overtime,” a propulsive anthem which begins with a “Star Spangled Banner” guitar lick, offers a litany of oppressive challenges (“a mean, mean gene in my family tree” and complaints about his “songs sound[ing] the same,” among them). A triumphant swirl of horns, guitars and drums imply what we already know: Bryan’s work is at a career, emotional high. Bryan mines the depth of grief across multiple moments on Zach Bryan—sometimes emerging with silver linings and suggestions of a better path forward, and sometimes not. The affecting “East Side of Sorrow” offers a strikingly precise (but widely relatable) tale that scales fighting a seemingly endless war, religious alienation and death. Amidst cascading tragedy, Bryan finds solace via expanding his horizons (“Stick out your chest, and then hit the road”) and offers a simple, but convincing, affirmation: “Let it be, then let it go”. Though Bryan spends his newest LP circling the same, reliable set of themes—love and its limitations, hopelessness and a deep well of resilience, etc.—you don’t emerge from the LP with a sense of linear narrative. Across 16 songs, relationships fail and prosper and then fail again; hope deteriorates and grows, only to deteriorate again. —Tom Williams