The 30 Best Indie Folk Albums of 2023

Only a few more lists to burn through before 2023 is over, and today we are looking at our favorite indie folk records of the year. It’s categorically one of our favorite genres, and these last 12 months have provided an absolute monsoon of great work to thumb through. From the early 2023 records by Tiny Ruins and Fenne Lily to the late-year triumphs by Nicole Dollanganger and Sufjan Stevens, it’s been an incredible run of days for acoustic-based instrumentation. Stay tuned for our hip-hop list on New Year’s Eve and, until then, here are our picks for the 30 best indie folk albums of 2023. —Matt Mitchell, Music Editor

AJJ: Disposable Everything

Disposable Everything is AJJ’s big reconciliation with the current state of affairs and the band’s place in all of it. What role should five men have in preserving any semblance of goodness that might still be left in this country? On Disposable Everything, AJJ aren’t quite sure they should have a role at all. In a world plagued by mainstream artists attempting to spin shallow money-grabs into wholehearted, political decrees, the band is not all that interested in shining the empathy on in ways they cannot authentically provide. There is no demand for revolution on this album; only the stark realization by the men who made it that they, too, have been lubing the cog that makes the machine of inequity crawl forward. Disposable Everything knocks on the door of modern masterpiece status, as AJJ have taken every single thing they do well, shoved it into a blender and made a chunky, absurd, glorious, gilded smoothie with it. —Matt Mitchell

Disposable Everything is AJJ’s big reconciliation with the current state of affairs and the band’s place in all of it. What role should five men have in preserving any semblance of goodness that might still be left in this country? On Disposable Everything, AJJ aren’t quite sure they should have a role at all. In a world plagued by mainstream artists attempting to spin shallow money-grabs into wholehearted, political decrees, the band is not all that interested in shining the empathy on in ways they cannot authentically provide. There is no demand for revolution on this album; only the stark realization by the men who made it that they, too, have been lubing the cog that makes the machine of inequity crawl forward. Disposable Everything knocks on the door of modern masterpiece status, as AJJ have taken every single thing they do well, shoved it into a blender and made a chunky, absurd, glorious, gilded smoothie with it. —Matt Mitchell

Al Menne: Freak Accident

It may be easy—and a bit obvious—but I can’t really start anywhere but the beginning when delving into Freak Accident. “Kill Me Now,” the first album’s first single and opening track, is the kind of song that’s difficult to write about without sounding effusive to the point of fanaticism. For a burgeoning songwriter like Menne to write such an affecting, tightly-wound, and captivating song is a feat difficult to overstate. That isn’t to say this is coming completely out of nowhere; it’s true Menne was not the primary songwriter force behind Great Grandpa, but their lyricism and incredible sense of melody are all over Four Of Arrows. In particular, “Bloom” remains one of the best songs the band ever wrote—and Menne’s way with words is a primary reason why. “I get anxious on the weekend when it feels like I’m wasting time, then I think about Tom Petty who wrote his best songs when he was 39,” is a lyric I think about a lot when stuck in a spiral of self-loathing and misplaced anxiety. “Kill Me” is a similarly astute look at the throes of helpless attraction, taking the question “Do you remember sayin’ it scared you to death to know how much I love you?” and thinly spreading it over months of pain and confusion. They sing a lot about the desire to be understood and accepted on Freak Accident (that name itself arriving as a play on the isolation they felt growing up as a trans person), and does so with such a disarming grace that invokes an incredible amount of pathos. “And I wonder if she knows those little parts of me?” Menne asks on “Beth,” during a scene that’s almost unbearably intimate. “There’s joy in the pain of bein’ alone, when nobody knows you the way that you need them to,” goes “Kill Me.” —Sean Fennell [Read our full feature]

It may be easy—and a bit obvious—but I can’t really start anywhere but the beginning when delving into Freak Accident. “Kill Me Now,” the first album’s first single and opening track, is the kind of song that’s difficult to write about without sounding effusive to the point of fanaticism. For a burgeoning songwriter like Menne to write such an affecting, tightly-wound, and captivating song is a feat difficult to overstate. That isn’t to say this is coming completely out of nowhere; it’s true Menne was not the primary songwriter force behind Great Grandpa, but their lyricism and incredible sense of melody are all over Four Of Arrows. In particular, “Bloom” remains one of the best songs the band ever wrote—and Menne’s way with words is a primary reason why. “I get anxious on the weekend when it feels like I’m wasting time, then I think about Tom Petty who wrote his best songs when he was 39,” is a lyric I think about a lot when stuck in a spiral of self-loathing and misplaced anxiety. “Kill Me” is a similarly astute look at the throes of helpless attraction, taking the question “Do you remember sayin’ it scared you to death to know how much I love you?” and thinly spreading it over months of pain and confusion. They sing a lot about the desire to be understood and accepted on Freak Accident (that name itself arriving as a play on the isolation they felt growing up as a trans person), and does so with such a disarming grace that invokes an incredible amount of pathos. “And I wonder if she knows those little parts of me?” Menne asks on “Beth,” during a scene that’s almost unbearably intimate. “There’s joy in the pain of bein’ alone, when nobody knows you the way that you need them to,” goes “Kill Me.” —Sean Fennell [Read our full feature]

Allegra Krieger: I Keep My Feet On The Fragile Plane

I Keep My Feet On The Fragile Plane is a wildly successful catalog of the trials of early adulthood, providing a comfortable space to explore painful points on unrealized promise and acceptance. Krieger seems at home within the structures of her languid, smoldering ballads—though the fire burns hot when she picks up speed just a little bit, navigating her compelling vocal melodies with a loping acoustic guitar. What’s always present is her keen emotional intelligence and knack for finding levity. At the heart of her songs, one can always catch a glimpse of the feeling that everything really does work out in the end. This is true if you’re able to accept that you’ll always be on the “fragile plane,” the halfway point between where you were and where you’re going. Rest assured, Allegra Krieger’s there, too—making music to usher us through. —Emma Bowers

I Keep My Feet On The Fragile Plane is a wildly successful catalog of the trials of early adulthood, providing a comfortable space to explore painful points on unrealized promise and acceptance. Krieger seems at home within the structures of her languid, smoldering ballads—though the fire burns hot when she picks up speed just a little bit, navigating her compelling vocal melodies with a loping acoustic guitar. What’s always present is her keen emotional intelligence and knack for finding levity. At the heart of her songs, one can always catch a glimpse of the feeling that everything really does work out in the end. This is true if you’re able to accept that you’ll always be on the “fragile plane,” the halfway point between where you were and where you’re going. Rest assured, Allegra Krieger’s there, too—making music to usher us through. —Emma Bowers

Angie McMahon: Light, Dark, Light Again

Four years passed between Salt and Light, Dark, Light Again—and part of that can be credited to COVID, as is the case with an insurmountable number of artists. McMahon wanted to put out a record pretty soon after Salt was released—not least of all because that’s what industry cycles have come to expect of the artists who work within it. Most artists would probably embrace the fruits of being able to put out a record every year—or, in the case of some acts, multiple records in a year; but McMahon is fully aware of how, even though that kind of schedule would be rewarding from a prolific place, it’s just not the kind of musician she is. In making Light, Dark, Light Again, McMahon herself fully changed. The record became a mountain she had to climb, but that’s what it always needed to be. There’s a continuity between the songs on Salt and those on Light, Dark, Light Again. It’s a really special convergence that is, largely, a product of McMahon’s journey deeper into her own self-discovery. What drives her is trying to understand her emotional experiences and trying to understand the world by, first, understanding herself and sharing whatever she learns about surviving through vulnerability and connecting while remaining a sensitive, open-minded person. Salt germinated from a naive understanding of where her own imbalances and plateaus might have stemmed from, while Light, Dark, Light Again is this deftly mature and bold excavation of self-actualized truths and discomforts. There’s this sense that the call is very much coming from inside the house, and hearing McMahon work through that hard reality is, often, a revelation. There’s a bit of sentimentality on Light, Dark, Light Again. It interacts and intersects with the record’s recurring themes of self-care and spirituality. But, sometimes, the songs transcend sentimentality into something that’s much more precious. The thesis statement of the album begins with its title: Light, Dark, Light Again. This idea of cyclicality and emotional timelines, it’s palpable and you can hear the intervals of joy, sorrow and hope spinning across the project. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Four years passed between Salt and Light, Dark, Light Again—and part of that can be credited to COVID, as is the case with an insurmountable number of artists. McMahon wanted to put out a record pretty soon after Salt was released—not least of all because that’s what industry cycles have come to expect of the artists who work within it. Most artists would probably embrace the fruits of being able to put out a record every year—or, in the case of some acts, multiple records in a year; but McMahon is fully aware of how, even though that kind of schedule would be rewarding from a prolific place, it’s just not the kind of musician she is. In making Light, Dark, Light Again, McMahon herself fully changed. The record became a mountain she had to climb, but that’s what it always needed to be. There’s a continuity between the songs on Salt and those on Light, Dark, Light Again. It’s a really special convergence that is, largely, a product of McMahon’s journey deeper into her own self-discovery. What drives her is trying to understand her emotional experiences and trying to understand the world by, first, understanding herself and sharing whatever she learns about surviving through vulnerability and connecting while remaining a sensitive, open-minded person. Salt germinated from a naive understanding of where her own imbalances and plateaus might have stemmed from, while Light, Dark, Light Again is this deftly mature and bold excavation of self-actualized truths and discomforts. There’s this sense that the call is very much coming from inside the house, and hearing McMahon work through that hard reality is, often, a revelation. There’s a bit of sentimentality on Light, Dark, Light Again. It interacts and intersects with the record’s recurring themes of self-care and spirituality. But, sometimes, the songs transcend sentimentality into something that’s much more precious. The thesis statement of the album begins with its title: Light, Dark, Light Again. This idea of cyclicality and emotional timelines, it’s palpable and you can hear the intervals of joy, sorrow and hope spinning across the project. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Anjimile: The King

Where his debut album Giver Taker explored a more delicate form of personal storytelling—often delivered via nimble, unadorned acoustic guitar flourishes in line with Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan or Illinois—Anjimile works on a much grander scale across The King, as if conjuring a vision of what folk music would sound like if it was delivered by Philip Glass. It’s a record akin to speaking with the force of every voice like Anjimile’s that has been left silent for centuries, arriving with a volume and might that feels primed to shatter anything that gets in its way. Guitar strings now thrum and buzz where they once felt gentle, and Anjimile’s voice is occasionally put through bass-heavy filters or joined by a calamitous, otherworldly choir sonorous enough to make the speakers rattle. Anjimile’s choice to radically reconfigure the basics of his sound is nothing short of revelatory. Much of The King comes solely from Anjimile’s guitar and voice, even if the record’s production makes it sound as if the tracks are being wrought by a cataclysmic full band. If there’s one thing that The King’s sound especially works to highlight, it’s Anjimile’s lyricism. Much of Giver Taker operated in similar narratives of family history and self-definition, but The King weds that focus to its sound even further, its assuredness more emphatic, its openness all the more vulnerable. And, on tracks like “Harley,” where Anjimile sings into a reverb-heavy soundscape for one of the rawer personal moments of songwriting, the transition explores new, audacious configurations that their emotional side can take. —Natalie Marlin [Read our full feature]

Where his debut album Giver Taker explored a more delicate form of personal storytelling—often delivered via nimble, unadorned acoustic guitar flourishes in line with Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan or Illinois—Anjimile works on a much grander scale across The King, as if conjuring a vision of what folk music would sound like if it was delivered by Philip Glass. It’s a record akin to speaking with the force of every voice like Anjimile’s that has been left silent for centuries, arriving with a volume and might that feels primed to shatter anything that gets in its way. Guitar strings now thrum and buzz where they once felt gentle, and Anjimile’s voice is occasionally put through bass-heavy filters or joined by a calamitous, otherworldly choir sonorous enough to make the speakers rattle. Anjimile’s choice to radically reconfigure the basics of his sound is nothing short of revelatory. Much of The King comes solely from Anjimile’s guitar and voice, even if the record’s production makes it sound as if the tracks are being wrought by a cataclysmic full band. If there’s one thing that The King’s sound especially works to highlight, it’s Anjimile’s lyricism. Much of Giver Taker operated in similar narratives of family history and self-definition, but The King weds that focus to its sound even further, its assuredness more emphatic, its openness all the more vulnerable. And, on tracks like “Harley,” where Anjimile sings into a reverb-heavy soundscape for one of the rawer personal moments of songwriting, the transition explores new, audacious configurations that their emotional side can take. —Natalie Marlin [Read our full feature]

Another Michael: Wishes to Fulfill

The first of two albums that will be released within six months of each other, Wishes to Fulfill is Another Michael at their very best. What they accomplished on their debut, New Music and Big Pop, two years ago gets hammed up even more so here, as Michael Doherty and Nick Sebastiano continue to prove that they are one of the most charming and talented and graceful duos in all of indie rock. Between Doherty’s stirring falsetto and Sebastiano’s pristine production choices, Wishes to Fulfill is an amalgam worth untangling over and over. Songs like “Baseball Player” and “Angel” are definitive earworms, while other standouts like “Piano Lessons” and “Candle” continue to establish the duo’s sound with endearing, bright and rich storytelling merged with fluttering, buoyant instrumentation. Suffice to say, we can’t wait for Pick Me Up, Turn Me Upside Down in 2024. —Matt Mitchell

The first of two albums that will be released within six months of each other, Wishes to Fulfill is Another Michael at their very best. What they accomplished on their debut, New Music and Big Pop, two years ago gets hammed up even more so here, as Michael Doherty and Nick Sebastiano continue to prove that they are one of the most charming and talented and graceful duos in all of indie rock. Between Doherty’s stirring falsetto and Sebastiano’s pristine production choices, Wishes to Fulfill is an amalgam worth untangling over and over. Songs like “Baseball Player” and “Angel” are definitive earworms, while other standouts like “Piano Lessons” and “Candle” continue to establish the duo’s sound with endearing, bright and rich storytelling merged with fluttering, buoyant instrumentation. Suffice to say, we can’t wait for Pick Me Up, Turn Me Upside Down in 2024. —Matt Mitchell

Caroline Rose: The Art of Forgetting

The Art of Forgetting, the latest album from Nashville singer/songwriter Caroline Rose is a departure in both theme and production from their previous release. While Superstar paid homage to ’80s cinema and a culture obsessed with celebrities, The Art of Forgetting finds inspiration through Balkan cries and the natural life cycles of handcrafted instruments. Although Rose has created fictionalized characters before, here they delve deep into their vulnerabilities and pain in a memoir of healing. Their portrayal of a new beginning during the first three tracks is visceral and guttural; “Tell Me What You Want” is undoubtedly the best track on the album. The witty and literal lyrics are bolstered by gritty guitar and Rose singing, “I just gotta take a beat / To get some fresh air in my lungs.” It’s fabulously dynamic in texture with different fortes and meticulous phrasing. Rose has reached new heights on this record, executing her ideas flawlessly. —Rayne Antrim

The Art of Forgetting, the latest album from Nashville singer/songwriter Caroline Rose is a departure in both theme and production from their previous release. While Superstar paid homage to ’80s cinema and a culture obsessed with celebrities, The Art of Forgetting finds inspiration through Balkan cries and the natural life cycles of handcrafted instruments. Although Rose has created fictionalized characters before, here they delve deep into their vulnerabilities and pain in a memoir of healing. Their portrayal of a new beginning during the first three tracks is visceral and guttural; “Tell Me What You Want” is undoubtedly the best track on the album. The witty and literal lyrics are bolstered by gritty guitar and Rose singing, “I just gotta take a beat / To get some fresh air in my lungs.” It’s fabulously dynamic in texture with different fortes and meticulous phrasing. Rose has reached new heights on this record, executing her ideas flawlessly. —Rayne Antrim

Charlotte Cornfield: Could Have Done Anything

Could Have Done Anything is Charlotte Cornfield’s fifth album and her clearest-eyed assemblage of songs yet. The first single, “You and Me,” gave us a glimpse into how the Canadian singer/songwriter has been watching the world over the last two years. It was an engrossing love song that made pit stops across the US, touching down in Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and the Rocky Mountains. Second single “Cut and Dry” is such a perfect example of why Cornfield is one of our best living songwriters. She paints a beautiful portrait around the melancholy of leaving. The story she tells, it’s emotional and poised and alive. “Sometimes we think that we know everything but / Then get surprised when the whole world comes crashing down / It’s hard to picture the city without you around,” she sings atop a combination of breezy guitars, vocalizations and horns. “Cut and Dry” is akin to many of Cornfield’s songs: Her taking the smallest moments and finding everlasting beauty within the margins. It’s a perfect coming-of-age folk song. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Could Have Done Anything is Charlotte Cornfield’s fifth album and her clearest-eyed assemblage of songs yet. The first single, “You and Me,” gave us a glimpse into how the Canadian singer/songwriter has been watching the world over the last two years. It was an engrossing love song that made pit stops across the US, touching down in Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and the Rocky Mountains. Second single “Cut and Dry” is such a perfect example of why Cornfield is one of our best living songwriters. She paints a beautiful portrait around the melancholy of leaving. The story she tells, it’s emotional and poised and alive. “Sometimes we think that we know everything but / Then get surprised when the whole world comes crashing down / It’s hard to picture the city without you around,” she sings atop a combination of breezy guitars, vocalizations and horns. “Cut and Dry” is akin to many of Cornfield’s songs: Her taking the smallest moments and finding everlasting beauty within the margins. It’s a perfect coming-of-age folk song. —Matt Mitchell [Read our full feature]

Daneshevskaya: Long Is The Tunnel

Long Is The Tunnel begins fully submerged. Rain is the first sound on the album’s opening track, “Challenger Deep,” the drops falling to announce the coming of a gentle fingerpicking. Next comes Anna Beckerman’s voice, an understated captivation that stuns with its soft strength. She sings “Will you wait for me / Where there is no later on? / Will you wait for me at the end, the end?,” drawing out each word, pausing between phrases—her voice arriving wrapped in silk but sung with desperation. There is a heaviness to her vocal, something substantive to grasp onto despite her lilting melancholia. She reaches her hand up through the water’s surface, begging you to reach out and pull her from her drowning. Laced with distortion and supple synth notes, “Big Bird” aches through bursting percussion and Beckerman’s airy singing that thins out into a beautiful, angelic falsetto. “The biggest bird I’ve ever seen,” she intones. “I don’t know what the reason was. I can’t tell a dove from the biggest bird I’ve ever seen.” It’s an earworm melody that rises and falls and glitters, culminating in a field recording of birds flocking to some unknown destination. Long Is The Tunnel ends on a gentle, elusive and captivating note, as final track “Ice Pigeon” opens to twinkling piano keys—almost ironically so. It could soundtrack the opening to a music box of her own history but, firstly, it ties together the record’s surrealist charm—most emphatically when she sings “Everything that comes out of your mouth is gold / But it’s useless to me / Cause I know what it needs.” —Madelyn Dawson [Read our full feature]

Long Is The Tunnel begins fully submerged. Rain is the first sound on the album’s opening track, “Challenger Deep,” the drops falling to announce the coming of a gentle fingerpicking. Next comes Anna Beckerman’s voice, an understated captivation that stuns with its soft strength. She sings “Will you wait for me / Where there is no later on? / Will you wait for me at the end, the end?,” drawing out each word, pausing between phrases—her voice arriving wrapped in silk but sung with desperation. There is a heaviness to her vocal, something substantive to grasp onto despite her lilting melancholia. She reaches her hand up through the water’s surface, begging you to reach out and pull her from her drowning. Laced with distortion and supple synth notes, “Big Bird” aches through bursting percussion and Beckerman’s airy singing that thins out into a beautiful, angelic falsetto. “The biggest bird I’ve ever seen,” she intones. “I don’t know what the reason was. I can’t tell a dove from the biggest bird I’ve ever seen.” It’s an earworm melody that rises and falls and glitters, culminating in a field recording of birds flocking to some unknown destination. Long Is The Tunnel ends on a gentle, elusive and captivating note, as final track “Ice Pigeon” opens to twinkling piano keys—almost ironically so. It could soundtrack the opening to a music box of her own history but, firstly, it ties together the record’s surrealist charm—most emphatically when she sings “Everything that comes out of your mouth is gold / But it’s useless to me / Cause I know what it needs.” —Madelyn Dawson [Read our full feature]

Fenne Lily: Big Picture

It isn’t easy to traffic in subtleties. Where many of today’s best indie-adjacent projects thrive in minimalism—in the style of Florist—or in hooky maximalism—a la Phoebe Bridgers—Fenne Lily seeks a Goldilocks-esque, happy medium, balancing delicate instrumental layers with pensive vocal delivery. On Big Picture, she handles her emotions with caution, as if she writes while wearing oven mitts, and her restraint makes her sharpest lines pierce even deeper. Take the first lyric of opener “Map of Japan”: “I never asked you to change and you’re treating me like I did / The more I’m thinking about it, maybe I should’ve started.” Delivered plainly over sauntering percussion and splendorous guitar, the hard pill she administers goes down sweetly. Big Picture is an exercise in excavating Lily’s last couple of years: A tumultuous period marked by transitions accelerated through 2020’s unending calamities. As she unpacks her memories, there are undeniable pangs of sadness and longing—but there are also moments of tender revelation that betray the soothing quality of memory. Across the album’s 10 tracks, Lily displays her memories with care, inviting listeners to occupy her vantage point, encouraging them to sit in the discomfort she endured and through which she found new possibilities. Big Picture is a successful meditation on tension, an act of sitting in discomfort. Fenne Lily has become a veritable expert on the subject, and her approach to narrating that process is engaging and novel. One can only hope that these contradicting feelings meet resolution sometime soon, but, for now, the music is thoroughly appealing. —Devon Chodzin [Read our full feature]

It isn’t easy to traffic in subtleties. Where many of today’s best indie-adjacent projects thrive in minimalism—in the style of Florist—or in hooky maximalism—a la Phoebe Bridgers—Fenne Lily seeks a Goldilocks-esque, happy medium, balancing delicate instrumental layers with pensive vocal delivery. On Big Picture, she handles her emotions with caution, as if she writes while wearing oven mitts, and her restraint makes her sharpest lines pierce even deeper. Take the first lyric of opener “Map of Japan”: “I never asked you to change and you’re treating me like I did / The more I’m thinking about it, maybe I should’ve started.” Delivered plainly over sauntering percussion and splendorous guitar, the hard pill she administers goes down sweetly. Big Picture is an exercise in excavating Lily’s last couple of years: A tumultuous period marked by transitions accelerated through 2020’s unending calamities. As she unpacks her memories, there are undeniable pangs of sadness and longing—but there are also moments of tender revelation that betray the soothing quality of memory. Across the album’s 10 tracks, Lily displays her memories with care, inviting listeners to occupy her vantage point, encouraging them to sit in the discomfort she endured and through which she found new possibilities. Big Picture is a successful meditation on tension, an act of sitting in discomfort. Fenne Lily has become a veritable expert on the subject, and her approach to narrating that process is engaging and novel. One can only hope that these contradicting feelings meet resolution sometime soon, but, for now, the music is thoroughly appealing. —Devon Chodzin [Read our full feature]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The debut album by Free Range—the project of Chicago-based singer-songwriter Sofia Jensen—feels like it’s always existed. “Want to Know,” one of Practice’s singles, exudes a familiarity based on Waxahatchee-esque acoustic guitars and muted drumming while obscuring a lyrical gut punch. By the time the song reveals a fuzzed out, country guitar lead and a strange, tight groove to wrap things up, the heartbreak becomes clear: “Don’t float back up without me / I don’t know how we’re supposed to talk.” Somewhere between the endless comfort of Wild Pink and the tight craftsmanship of those Adrianne Lenker/Buck Meek albums, Practice is an album that shows confidence from the first note. Beyond “Want to Know,” the rest of the record is just as exciting, from the campfire haziness of “All My Thoughts” and the double-tracked vocals on “Traveling Song” to the blurry pianos of “Keep In Time.” With Practice, Jensen takes the strengths of their inspirations (Elliot Smith, Scandinavian forests, David Foster Wallace) and applies them to devastatingly beautiful songs. —Ethan Beck

The debut album by Free Range—the project of Chicago-based singer-songwriter Sofia Jensen—feels like it’s always existed. “Want to Know,” one of Practice’s singles, exudes a familiarity based on Waxahatchee-esque acoustic guitars and muted drumming while obscuring a lyrical gut punch. By the time the song reveals a fuzzed out, country guitar lead and a strange, tight groove to wrap things up, the heartbreak becomes clear: “Don’t float back up without me / I don’t know how we’re supposed to talk.” Somewhere between the endless comfort of Wild Pink and the tight craftsmanship of those Adrianne Lenker/Buck Meek albums, Practice is an album that shows confidence from the first note. Beyond “Want to Know,” the rest of the record is just as exciting, from the campfire haziness of “All My Thoughts” and the double-tracked vocals on “Traveling Song” to the blurry pianos of “Keep In Time.” With Practice, Jensen takes the strengths of their inspirations (Elliot Smith, Scandinavian forests, David Foster Wallace) and applies them to devastatingly beautiful songs. —Ethan Beck “Picking up the things you left / I never thought I’d be so upset” are the lines Greg Mendez uses to open his new, self-titled album. It’s a fitting entrance for the Philadelphian, as he spends the next nine songs putting back together the fragments of his own life—attempting to understand the absurdity of his own truth and what hard damage has met him on the road to clarity. Ever the master of his storytelling craft, Mendez makes a bookend out of imagery that can be plugged into anyone’s own correspondence with the world around them. Greg Mendez is one man’s vulnerable, open book made accessible to anyone who might find something courageous or trusting within it. From drug use to heartbreak to childhood trauma to houselessness, Mendez offers a loving embrace drenched with hindsight to his former self. In turn, the album is not a critique of his past, but an attempt at understanding how it informs his personhood in the present. He populates the tracklist with recoiling and punctuated stories that are as humorous as they are heartbreaking. —Matt Mitchell

“Picking up the things you left / I never thought I’d be so upset” are the lines Greg Mendez uses to open his new, self-titled album. It’s a fitting entrance for the Philadelphian, as he spends the next nine songs putting back together the fragments of his own life—attempting to understand the absurdity of his own truth and what hard damage has met him on the road to clarity. Ever the master of his storytelling craft, Mendez makes a bookend out of imagery that can be plugged into anyone’s own correspondence with the world around them. Greg Mendez is one man’s vulnerable, open book made accessible to anyone who might find something courageous or trusting within it. From drug use to heartbreak to childhood trauma to houselessness, Mendez offers a loving embrace drenched with hindsight to his former self. In turn, the album is not a critique of his past, but an attempt at understanding how it informs his personhood in the present. He populates the tracklist with recoiling and punctuated stories that are as humorous as they are heartbreaking. —Matt Mitchell The debut solo album from the Fontaines D.C. frontman, Chaos For The Fly is a brilliant, honest effort by Grian Chatten. Rather than feed into the biting arrangements that make Fontaines D.C. so blistering and raw, Chatten taps into the lighter side of his own grit. “Last Time Every Time Forever” is a subtle acoustic tune wrapped in digital backbeats, reverb and heavenly harmonies. “Fairlies” is an uptempo folk carving with jazz energy, while “Salt Throwers Off a Truck” is a strumming odyssey filled out with a buoyant spine of crooning strings. Chatten is miles away from what he and his bandmates did on Skinty Fia last year, but that’s what makes Chaos For The Fly so great. It’s a fresh, gutsy and mature first chapter for the Irish singer/songwriter that’s sure to become a bedrock of European folklore. —Matt Mitchell

The debut solo album from the Fontaines D.C. frontman, Chaos For The Fly is a brilliant, honest effort by Grian Chatten. Rather than feed into the biting arrangements that make Fontaines D.C. so blistering and raw, Chatten taps into the lighter side of his own grit. “Last Time Every Time Forever” is a subtle acoustic tune wrapped in digital backbeats, reverb and heavenly harmonies. “Fairlies” is an uptempo folk carving with jazz energy, while “Salt Throwers Off a Truck” is a strumming odyssey filled out with a buoyant spine of crooning strings. Chatten is miles away from what he and his bandmates did on Skinty Fia last year, but that’s what makes Chaos For The Fly so great. It’s a fresh, gutsy and mature first chapter for the Irish singer/songwriter that’s sure to become a bedrock of European folklore. —Matt Mitchell The tracks on The Window Is The Dream are still as dainty and minimal as ever, but, now, there’s a new edge to all of them. Horn doesn’t get too personal in her storytelling, but she doesn’t need to. The songs evoke visceral emotion through the architecture of her sonic vision. It doesn’t hurt that she has an incredible ecosystem of musicians around her, including Jared Samuel Elioseff, Adam Jones, Jonathan Horne, Daniel Francis Doyle and Sarah La Puerta Gautier. The Window Is The Dream is a bit more electric than Optimism was, thanks to Horne’s splendid guitar work. That aural upgrade pairs well with Horn’s hypnotizing soprano vocals, which are sharper than ever. Though it’s only been a year since Optimism was put back on all of our radars, Horn has grown exponentially between records, making The Window Is The Dream a small triumph at the beginning of—what will likely be—a long, winding career. —Matt Mitchell [

The tracks on The Window Is The Dream are still as dainty and minimal as ever, but, now, there’s a new edge to all of them. Horn doesn’t get too personal in her storytelling, but she doesn’t need to. The songs evoke visceral emotion through the architecture of her sonic vision. It doesn’t hurt that she has an incredible ecosystem of musicians around her, including Jared Samuel Elioseff, Adam Jones, Jonathan Horne, Daniel Francis Doyle and Sarah La Puerta Gautier. The Window Is The Dream is a bit more electric than Optimism was, thanks to Horne’s splendid guitar work. That aural upgrade pairs well with Horn’s hypnotizing soprano vocals, which are sharper than ever. Though it’s only been a year since Optimism was put back on all of our radars, Horn has grown exponentially between records, making The Window Is The Dream a small triumph at the beginning of—what will likely be—a long, winding career. —Matt Mitchell [ Kacey Johansing’s fifth album is a thing to behold.

Kacey Johansing’s fifth album is a thing to behold.  Katie Von Schleicher recorded A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night with Sam Evian and a crew of collaborators she had worked with on other projects, including Baroness bassist Nick Jost and Gabriel Birnbaum, her Wilder Maker bandmate, who did string arrangements here. The result is her most sophisticated and wide-ranging album and arguably her freest. Von Schleicher has the uncertainty she often feels while working on her albums, which sometimes manifests in taut, volatile moments in the music: the contrast between the explosive percussion and her somber vocals on “The Image,” from 2017’s Shitty Hits, for example, or the juxtaposition between her soft voice and the deep sense of anger in her lyrics on “You Remind Me,” from Cosummation. There’s little of that on A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night. These 10 songs feel easy, though they’re certainly not simple. If not for the melancholy tone, “Every Step Is an Ocean” would be breezy, thanks to a limber beat, airy synthesizers and Birnbaums’s string charts, which dart and swirl through the song. Elsewhere, she leans into a deadpan slacker-rock vibe on “Elixir,” which opens with her singing, “I wear becoming like a burlap sack.” A buzzy, 20-second guitar break early in the song gets a reprise of sorts toward the end when Von Schleicher turns it into a string of wordless vocals she sings almost without inflection, and the whole thing is punchy and droll. Toward the end of the album, “Ruby” is as buoyant a song musically as Von Schleicher has written, with blooms of keyboards rising through a metronomic beat, and string parts that come seeping in at the edges with cinematic flair. With lyrics that seem to have a sardonic, mocking edge, it’s not a happy song—Von Schleicher hasn’t reinvented herself or anything—but it’s a compelling listen. That holds true for A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night as a whole. By some alchemical blend of age, accumulated experience or just the right collaborators in the right setting, Katie Von Schleicher has found a way to be comfortable with herself and her songs, and it shows—just like her sense of humor. —Eric R. Danton

Katie Von Schleicher recorded A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night with Sam Evian and a crew of collaborators she had worked with on other projects, including Baroness bassist Nick Jost and Gabriel Birnbaum, her Wilder Maker bandmate, who did string arrangements here. The result is her most sophisticated and wide-ranging album and arguably her freest. Von Schleicher has the uncertainty she often feels while working on her albums, which sometimes manifests in taut, volatile moments in the music: the contrast between the explosive percussion and her somber vocals on “The Image,” from 2017’s Shitty Hits, for example, or the juxtaposition between her soft voice and the deep sense of anger in her lyrics on “You Remind Me,” from Cosummation. There’s little of that on A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night. These 10 songs feel easy, though they’re certainly not simple. If not for the melancholy tone, “Every Step Is an Ocean” would be breezy, thanks to a limber beat, airy synthesizers and Birnbaums’s string charts, which dart and swirl through the song. Elsewhere, she leans into a deadpan slacker-rock vibe on “Elixir,” which opens with her singing, “I wear becoming like a burlap sack.” A buzzy, 20-second guitar break early in the song gets a reprise of sorts toward the end when Von Schleicher turns it into a string of wordless vocals she sings almost without inflection, and the whole thing is punchy and droll. Toward the end of the album, “Ruby” is as buoyant a song musically as Von Schleicher has written, with blooms of keyboards rising through a metronomic beat, and string parts that come seeping in at the edges with cinematic flair. With lyrics that seem to have a sardonic, mocking edge, it’s not a happy song—Von Schleicher hasn’t reinvented herself or anything—but it’s a compelling listen. That holds true for A Little Touch of Schleicher in the Night as a whole. By some alchemical blend of age, accumulated experience or just the right collaborators in the right setting, Katie Von Schleicher has found a way to be comfortable with herself and her songs, and it shows—just like her sense of humor. —Eric R. Danton Christina Schneider’s music has always been an oddity. Whether the subject of analysis is her litany of previous projects—with curious names like Jepeto Solutions and C.E. Schneider’s Genius Grant, or her current, most circulated project, Locate S,1—Schneider’s not one to simplify her music. Across two albums as Locate S,1, her striking admiration for pop music is apparent, but so is her need to wrestle with her intellect. On her last record, 2020’s Personalia, Schneider’s sonic palette was diverse but centered on variations of synth-pop, twisted and restrung with elements of punk, new wave and more. Now, on her third album, Wicked Jaw, the stylistic and subjective floodgates are wider than ever. “I was in hell…and loving it,” offered Schneider on the subject of her childhood. While the phrase “there’s so much to unpack here” is often uttered for albums that are, in actuality, narrow in scope, Wicked Jaw is an inter-dimensional trip through Schneider’s past, present and future. There really is a lot to unpack. All the while, her appreciation for all eras and approaches to pop music arrive through forays into bossa nova, doo-wop and soft rock—all with head-scratching complexity. Sophisticated, twisted embellishments to her pop hooks interrupt the sunshine with interjections of personal and generational trauma, all wrapped up with a healthy existentialism. Whether she is processing something from childhood or something that happened yesterday, she examines it best through intricate, pop-inspired sonic webs. —Devon Chodzin

Christina Schneider’s music has always been an oddity. Whether the subject of analysis is her litany of previous projects—with curious names like Jepeto Solutions and C.E. Schneider’s Genius Grant, or her current, most circulated project, Locate S,1—Schneider’s not one to simplify her music. Across two albums as Locate S,1, her striking admiration for pop music is apparent, but so is her need to wrestle with her intellect. On her last record, 2020’s Personalia, Schneider’s sonic palette was diverse but centered on variations of synth-pop, twisted and restrung with elements of punk, new wave and more. Now, on her third album, Wicked Jaw, the stylistic and subjective floodgates are wider than ever. “I was in hell…and loving it,” offered Schneider on the subject of her childhood. While the phrase “there’s so much to unpack here” is often uttered for albums that are, in actuality, narrow in scope, Wicked Jaw is an inter-dimensional trip through Schneider’s past, present and future. There really is a lot to unpack. All the while, her appreciation for all eras and approaches to pop music arrive through forays into bossa nova, doo-wop and soft rock—all with head-scratching complexity. Sophisticated, twisted embellishments to her pop hooks interrupt the sunshine with interjections of personal and generational trauma, all wrapped up with a healthy existentialism. Whether she is processing something from childhood or something that happened yesterday, she examines it best through intricate, pop-inspired sonic webs. —Devon Chodzin The debut album from Nashville singer/songwriter Mali Velasquez,

The debut album from Nashville singer/songwriter Mali Velasquez,  Spike Field is a dreamy soundscape of the multi-instrumentalist’s inner conflict of past and future self. As a young artist who began the journey of Maria BC during the pandemic, self-reflection has always been deeply embedded in their work. Spike Field confronts the shame of their past to reconcile who they were to be comfortable with who they become. The ambient folk artist’s soft vocals float across the eerie landscape of the raw emotions of “Still” however, they soar in choral passion in “Watcher.” In an album wrought with potent imagery, the album’s namesake provides a quiet contemplation of human communication through the concept of menacing earthworks. The atmospheric album combines Maria BC’s talents as a poet and classically trained vocalist, all emphasized through their passion for experimenting with human sounds. In all its morose beauty, Maria BC provides honest commentary on the painful truth of the shame of growing up. —Olivia Abercrombie [

Spike Field is a dreamy soundscape of the multi-instrumentalist’s inner conflict of past and future self. As a young artist who began the journey of Maria BC during the pandemic, self-reflection has always been deeply embedded in their work. Spike Field confronts the shame of their past to reconcile who they were to be comfortable with who they become. The ambient folk artist’s soft vocals float across the eerie landscape of the raw emotions of “Still” however, they soar in choral passion in “Watcher.” In an album wrought with potent imagery, the album’s namesake provides a quiet contemplation of human communication through the concept of menacing earthworks. The atmospheric album combines Maria BC’s talents as a poet and classically trained vocalist, all emphasized through their passion for experimenting with human sounds. In all its morose beauty, Maria BC provides honest commentary on the painful truth of the shame of growing up. —Olivia Abercrombie [ Mitski’s seventh album feels, all at once, like a much-needed course correction away from ‘80s-style synths growing staler with each use and like her lowest stakes release yet. The towering expectation and deafening hype that surrounded Laurel Hell seemed to have died down, leaving her free to exhale. The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We finds Mitski breaking new ground, building transcendent songs with the accompaniment of acoustic guitars, pedal steel, a string section and an entire 17-person choir. These resplendent pieces fit together to form fascinating, delicately arranged songs. One of the most striking things about the record is how it succeeds while sacrificing the reliance on melody that undergirds some of Mitski’s best songwriting thus far. There is nothing as electric as “Nobody,” nothing as distorted as “Your Best American Girl.” And yet, this is her finest collection of songs. There’s a beauty to her pastoral vignettes that resonates without the need for traditional pop hooks. It’s not music that’s suited to arenas, and maybe that’s the point. Mitski can do anything she wants to now, and we’re better off under her reign. —Eric Bennett

Mitski’s seventh album feels, all at once, like a much-needed course correction away from ‘80s-style synths growing staler with each use and like her lowest stakes release yet. The towering expectation and deafening hype that surrounded Laurel Hell seemed to have died down, leaving her free to exhale. The Land is Inhospitable and So Are We finds Mitski breaking new ground, building transcendent songs with the accompaniment of acoustic guitars, pedal steel, a string section and an entire 17-person choir. These resplendent pieces fit together to form fascinating, delicately arranged songs. One of the most striking things about the record is how it succeeds while sacrificing the reliance on melody that undergirds some of Mitski’s best songwriting thus far. There is nothing as electric as “Nobody,” nothing as distorted as “Your Best American Girl.” And yet, this is her finest collection of songs. There’s a beauty to her pastoral vignettes that resonates without the need for traditional pop hooks. It’s not music that’s suited to arenas, and maybe that’s the point. Mitski can do anything she wants to now, and we’re better off under her reign. —Eric Bennett The latest album from experimental multi-instrumentalist Mutual Benefit, Growing at the Edges, sees Jordan Lee place a coda on a five-years-long effort in growth. The album is a lesson in opening the wounds of old questions and looking for better answers. The song “Little Ways” is a calm, country-driven acoustic track about growing up and out, a fitting intro to the album it rises from. It reads like a mantra, a last glance backwards before the slow trudge into the unknown gets underway. Unhurried and sweet, the track—much like the album altogether—rolls forward on the wheels of its own optimism. “Wasteland Companions” leans heavily into its own lush instrumentals, swirly and saxophonic. It’s replete with xylopones, violins, drums and dreamy piano, with Lee’s light voice riding atop the gentle multi-part wave of end ebbing and flowing backing track. It traces closure and forward-motion after grief and loss; Growing at the Edges is pop construction at its finest. —Miranda Wollen

The latest album from experimental multi-instrumentalist Mutual Benefit, Growing at the Edges, sees Jordan Lee place a coda on a five-years-long effort in growth. The album is a lesson in opening the wounds of old questions and looking for better answers. The song “Little Ways” is a calm, country-driven acoustic track about growing up and out, a fitting intro to the album it rises from. It reads like a mantra, a last glance backwards before the slow trudge into the unknown gets underway. Unhurried and sweet, the track—much like the album altogether—rolls forward on the wheels of its own optimism. “Wasteland Companions” leans heavily into its own lush instrumentals, swirly and saxophonic. It’s replete with xylopones, violins, drums and dreamy piano, with Lee’s light voice riding atop the gentle multi-part wave of end ebbing and flowing backing track. It traces closure and forward-motion after grief and loss; Growing at the Edges is pop construction at its finest. —Miranda Wollen Canadian-American singer/songwriter Nicole Dollanganger’s latest LP, Married in Mount Airy, is her best work yet. It’s a record where her penchant for gothic folk storytelling and lo-fi, dream-pop textures converge brighter than ever, as Dollanganger takes her atmospheric, lush vocals and pairs them with tranquil, sublime acoustic instrumentation and synthesizer undercurrents. Songs like “Dogwood” and “Bad Man” and “Nymphs Finding the Head of Oprheus” are dynamic and stirring in their own interrogations of devotion, romance and traumatic, air-faded memories. What makes Dollanganger stand out from her peers, however, is how well she seamlessly guides listeners to conclusions through portraits of crushing familiarity, all told through subjects who are, all at once, harrowingly close yet so damningly distant. Married in Mount Airy doesn’t marr the lulls of heartache and uncomfortability, it embraces the cathartic of both and spins it into a darkness worth falling into. —Matt Mitchell

Canadian-American singer/songwriter Nicole Dollanganger’s latest LP, Married in Mount Airy, is her best work yet. It’s a record where her penchant for gothic folk storytelling and lo-fi, dream-pop textures converge brighter than ever, as Dollanganger takes her atmospheric, lush vocals and pairs them with tranquil, sublime acoustic instrumentation and synthesizer undercurrents. Songs like “Dogwood” and “Bad Man” and “Nymphs Finding the Head of Oprheus” are dynamic and stirring in their own interrogations of devotion, romance and traumatic, air-faded memories. What makes Dollanganger stand out from her peers, however, is how well she seamlessly guides listeners to conclusions through portraits of crushing familiarity, all told through subjects who are, all at once, harrowingly close yet so damningly distant. Married in Mount Airy doesn’t marr the lulls of heartache and uncomfortability, it embraces the cathartic of both and spins it into a darkness worth falling into. —Matt Mitchell On

On  The key line in “Shitty Town,” the powerful first single from Sarah Mary Chadwick’s new album Messages To God, comes towards the song’s rousing finale as she belts out the words, “Yeah I know I’m angry / why aren’t you?” It’s a question for the ages but feels especially appropriate nowadays when there’s so much to be furious about and so few people seem to notice. For the protagonist of this song, though, it’s a cry of desperation as they lament their circumstances and the awful place they’re stuck in. The depth of feeling in the song is only made more powerful via Chadwick’s quavering vocal delivery, which often sounds like the trumpet blast taking down Jericho’s walls, and the woodwinds that gives the music its gorgeous ache. The rest of the record speaks to such a truth, as Chadwick is at an apex here, on her brightest and boldest entry yet—a true feat, given that her catalog is packed to the brim with envelope-pushing brilliance. —Robert Ham

The key line in “Shitty Town,” the powerful first single from Sarah Mary Chadwick’s new album Messages To God, comes towards the song’s rousing finale as she belts out the words, “Yeah I know I’m angry / why aren’t you?” It’s a question for the ages but feels especially appropriate nowadays when there’s so much to be furious about and so few people seem to notice. For the protagonist of this song, though, it’s a cry of desperation as they lament their circumstances and the awful place they’re stuck in. The depth of feeling in the song is only made more powerful via Chadwick’s quavering vocal delivery, which often sounds like the trumpet blast taking down Jericho’s walls, and the woodwinds that gives the music its gorgeous ache. The rest of the record speaks to such a truth, as Chadwick is at an apex here, on her brightest and boldest entry yet—a true feat, given that her catalog is packed to the brim with envelope-pushing brilliance. —Robert Ham Although the album’s promotional cycle would have you believe Javelin is a straightforward extension of the gentle melancholy of Carrie & Lowell, that’s a slight misnomer. Rather, Sufjan Stevens’ latest blends the synth-driven freakouts of 2010’s The Age of Adz with his quieter endeavors. Most of Javelin concerns itself with past wrongdoings and the physical atonement, much of it self-induced, that its narrator undergoes as a result. “Give myself as a sacrifice / Genuflecting ghost as I kiss the floor,” Stevens’ opening couplet of “Genuflecting Ghost” goes, making immolation sound peaceful with arpeggiated acoustic guitars. Later in the song, he’s begging someone to “bind” and “insult” him as he “praise[s] your name.” This contrast of disturbing imagery and gorgeous, musical tapestries has long been one of Stevens’ strengths as a songwriter. The way he illustrates hopelessness is so affecting that, despite his quiet voice and instrumentation, his music refuses to recede into the background. It commands your attention in every conceivable way. —Grant Sharples

Although the album’s promotional cycle would have you believe Javelin is a straightforward extension of the gentle melancholy of Carrie & Lowell, that’s a slight misnomer. Rather, Sufjan Stevens’ latest blends the synth-driven freakouts of 2010’s The Age of Adz with his quieter endeavors. Most of Javelin concerns itself with past wrongdoings and the physical atonement, much of it self-induced, that its narrator undergoes as a result. “Give myself as a sacrifice / Genuflecting ghost as I kiss the floor,” Stevens’ opening couplet of “Genuflecting Ghost” goes, making immolation sound peaceful with arpeggiated acoustic guitars. Later in the song, he’s begging someone to “bind” and “insult” him as he “praise[s] your name.” This contrast of disturbing imagery and gorgeous, musical tapestries has long been one of Stevens’ strengths as a songwriter. The way he illustrates hopelessness is so affecting that, despite his quiet voice and instrumentation, his music refuses to recede into the background. It commands your attention in every conceivable way. —Grant Sharples Bad Dream Jaguar is a collection of songs threading their way through the uncertainty. The Austin band made the album during a period of dislocation: guitarist Stephen Salisbury moved from Texas to North Carolina in 2020, changing the nature of his creative (and romantic) relationship with singer and bandleader Laura Colwell until she joined him in 2022. The dozen tracks on Bad Dream Jaguar seek to make sense of that distance, their solitude and, in an overarching way, a fractured nostalgia for what had come before—and the often painful work of letting it go. It’s a subtle album, built around gentle, dream-like musical arrangements that belie the tougher sentiments underpinning these songs. The narrators here are often trying to figure out where they stand, in relation to a significant other, themselves, the past, the future. “You were searching for a reason to be mad / Babe, I got plenty of them,” Colwell sings on “Mixed Bag,” her soft voice wrapped in layers of guitar, ghostly backing vocals and a piano vamp that lands just so between lyrics. Befitting an album that took shape around a long-distance relationship, there’s a lot of road imagery on Bad Dream Jaguar. Colwell sings about long drives and headlights in the distance, and the lyrics often play like the reveries that blossom between the highway lines on road trips. She lets her mind wander through remembered scenes and settings that have the feel of creased snapshots she found tucked away in the glove compartment. Colwell is fighting to stay awake behind the wheel, and true to herself, while singing along in the car on “John Prine.” On “Washington Square,” her narrator is remembering when she and a partner were young and foolish “back when all the things to come hadn’t yet,” while “Sage” finds her holding tight to glimpses of the past while staving off the melancholy of a solitary present. —Eric R. Danton [

Bad Dream Jaguar is a collection of songs threading their way through the uncertainty. The Austin band made the album during a period of dislocation: guitarist Stephen Salisbury moved from Texas to North Carolina in 2020, changing the nature of his creative (and romantic) relationship with singer and bandleader Laura Colwell until she joined him in 2022. The dozen tracks on Bad Dream Jaguar seek to make sense of that distance, their solitude and, in an overarching way, a fractured nostalgia for what had come before—and the often painful work of letting it go. It’s a subtle album, built around gentle, dream-like musical arrangements that belie the tougher sentiments underpinning these songs. The narrators here are often trying to figure out where they stand, in relation to a significant other, themselves, the past, the future. “You were searching for a reason to be mad / Babe, I got plenty of them,” Colwell sings on “Mixed Bag,” her soft voice wrapped in layers of guitar, ghostly backing vocals and a piano vamp that lands just so between lyrics. Befitting an album that took shape around a long-distance relationship, there’s a lot of road imagery on Bad Dream Jaguar. Colwell sings about long drives and headlights in the distance, and the lyrics often play like the reveries that blossom between the highway lines on road trips. She lets her mind wander through remembered scenes and settings that have the feel of creased snapshots she found tucked away in the glove compartment. Colwell is fighting to stay awake behind the wheel, and true to herself, while singing along in the car on “John Prine.” On “Washington Square,” her narrator is remembering when she and a partner were young and foolish “back when all the things to come hadn’t yet,” while “Sage” finds her holding tight to glimpses of the past while staving off the melancholy of a solitary present. —Eric R. Danton [ Steve Ciolek has seen America many times over, but he’s content with staying in Ohio for as long as the state will hold both him and his buds. When he was fronting the Sidekicks—the Buckeye State’s beloved coterie of emo, power-pop sharks—hubs like Chicago, Brooklyn and Philadelphia were always destinations, but never fantasies of a possible forever.

Steve Ciolek has seen America many times over, but he’s content with staying in Ohio for as long as the state will hold both him and his buds. When he was fronting the Sidekicks—the Buckeye State’s beloved coterie of emo, power-pop sharks—hubs like Chicago, Brooklyn and Philadelphia were always destinations, but never fantasies of a possible forever.  During the pandemic, Kristian Matsson, aka The Tallest Man on Earth, would take song requests online and flip them into his own renditions in mere minutes. He played everything from a banjo translation of Mazzy Star’s “Fade Into You” to Vampire Weekend’s “Unbelievers,” fashioning them from shoegaze and pop rock into folk, Americana and bluegrass standards. For a small grain of time, Matsson was a beacon of community during a moment in history when community wasn’t possible—a perpendicular universe to what he’s constructed on his newest album, Henry St. Covering songs has always been familiar ground for Matsson. Sitting at the piano or plucking other peoples’ songs on the guitar is how he, like many of us, eventually vaulted into doing his own songwriting—no matter what it looked like. The team of musicians that Matsson assembled for the new album includes the Dead Tongues’ Ryan Gustafson on guitar, lap steel and ukulele, TJ Maiani on drums, Bon Iver’s CJ Camerieri and Rob Moose on trumpet, French horn and strings, Phil Cook on keys and Landlady’s Adam Schatz on saxophone. Overseeing the whole thing was Sylvan Esso’s Nick Sanborn, whose Durham studio Betty’s is where Henry St. came together. Every chapter and crosswalk on Henry St. looks and sounds different. It’s a kaleidoscopic pastiche of discovery: the stark piano of the title track melts into a ukulele dance on “In Your Garden Still”; the motivational drumming on “New Religion” quiets into a blanket of guitar and organ on closer “Foothills.” Gone are the days of guitar, guitar, guitar. Matsson’s music-making gift has never been so emblematic. —Matt Mitchell [

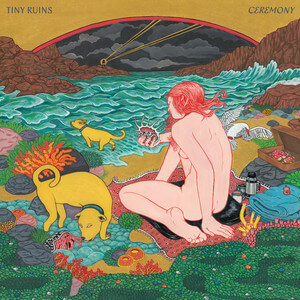

During the pandemic, Kristian Matsson, aka The Tallest Man on Earth, would take song requests online and flip them into his own renditions in mere minutes. He played everything from a banjo translation of Mazzy Star’s “Fade Into You” to Vampire Weekend’s “Unbelievers,” fashioning them from shoegaze and pop rock into folk, Americana and bluegrass standards. For a small grain of time, Matsson was a beacon of community during a moment in history when community wasn’t possible—a perpendicular universe to what he’s constructed on his newest album, Henry St. Covering songs has always been familiar ground for Matsson. Sitting at the piano or plucking other peoples’ songs on the guitar is how he, like many of us, eventually vaulted into doing his own songwriting—no matter what it looked like. The team of musicians that Matsson assembled for the new album includes the Dead Tongues’ Ryan Gustafson on guitar, lap steel and ukulele, TJ Maiani on drums, Bon Iver’s CJ Camerieri and Rob Moose on trumpet, French horn and strings, Phil Cook on keys and Landlady’s Adam Schatz on saxophone. Overseeing the whole thing was Sylvan Esso’s Nick Sanborn, whose Durham studio Betty’s is where Henry St. came together. Every chapter and crosswalk on Henry St. looks and sounds different. It’s a kaleidoscopic pastiche of discovery: the stark piano of the title track melts into a ukulele dance on “In Your Garden Still”; the motivational drumming on “New Religion” quiets into a blanket of guitar and organ on closer “Foothills.” Gone are the days of guitar, guitar, guitar. Matsson’s music-making gift has never been so emblematic. —Matt Mitchell [ Since 2009, New Zealand band Tiny Ruins have been steadily making good, blissful indie rock. Led by vocalist and guitarist Hollie Fullbrook, the band’s first record since 2019’s Olympic Girls, Ceremony was catalyzed by singles “Dorothy Bay,” “The Crab / Waterbaby” and “Out of Phase” The tracks lean into water imagery and folk instrumentation that spawn atop a smooth, hypnotic arrangement. Fullbrook’s lyrics are evocative and wondrous, and her vocals are soulful and weightless. “By hook or by the book, I can’t explain / How I miss the flowers made from cellophane / Little hands and paws, they trial and train / Keep you sifting sand in the outer lane,” she sings on “Dorothy Bay.” Ceremony is a great reintroduction to a beloved, steadfast indie band that demanded to not get lost amongst the shuffle of early 2023 releases. —Matt Mitchell

Since 2009, New Zealand band Tiny Ruins have been steadily making good, blissful indie rock. Led by vocalist and guitarist Hollie Fullbrook, the band’s first record since 2019’s Olympic Girls, Ceremony was catalyzed by singles “Dorothy Bay,” “The Crab / Waterbaby” and “Out of Phase” The tracks lean into water imagery and folk instrumentation that spawn atop a smooth, hypnotic arrangement. Fullbrook’s lyrics are evocative and wondrous, and her vocals are soulful and weightless. “By hook or by the book, I can’t explain / How I miss the flowers made from cellophane / Little hands and paws, they trial and train / Keep you sifting sand in the outer lane,” she sings on “Dorothy Bay.” Ceremony is a great reintroduction to a beloved, steadfast indie band that demanded to not get lost amongst the shuffle of early 2023 releases. —Matt Mitchell