The 50 Greatest Albums of 1994, Ranked

Here are our favorite albums from music's greatest year.

You could make the argument that the greatest year in music history was, and remains, 1994. In a decade met by unprecedented change and tides of trends bound by no certain direction, the year saw the death of Kurt Cobain unfold into a melting pot of country, jazz rap, dream pop, grunge, metal, ambient and fuzzy, lo-fi rock ‘n’ roll bubbling to the surface from the underground. Whether it was debut albums from Elliott Smith, Portishead, OutKast and Jeff Buckley, or mid-career gems from R.E.M., Nick Cave and Joni Mitchell, or beloved genre staples from Alan Jackson, Nas and Pavement, 1994 had everything you could ever want—and so much of it was so, so good. It’s hard to argue with the 100s of albums that came out in the mid-’90s. Whether it was a catalog-defining entry or a show-stopping debut, the proof is undeniable. We polled the Paste staff and writer cohort for this list. With that, here is our ranking of the 50 greatest albums of 1994.

50. Elliott Smith: Roman Candle

30 years on, I don’t think it’s radical to hold the opinion that Roman Candle, while great, is the “worst” of Elliott Smith’s six albums. It’s certainly the least fleshed out for obvious reasons, given the background of its recording. It’s redeemed by the fact that the songs are strong, even in their skeletal form, as Cavity Search clearly heard. The spareness is a matter of necessity, but you can tell it can bear the weight of dense arrangements—showcasing Smith’s often overlooked technical playing abilities. The only reason we might underrate it now is that we can look to what this seed of insane talent will build to, though the first record introduces thematic concerns and a penchant for melodic complexity that will show up again in subsequent records. Roman Candle, thematically, is all about halves—half-riddles, Irish goodbyes, phone calls where no one says what they really want to say and pleas to not talk about it. Even before his own drug use started, Elliott Smith always focused on dependence, capturing people drifting apart or coming back to things they depend on. I’m sure that reliance strikes further fury into the hearts of those who experience it, leaving them unsure where to turn. There’s an intimacy to the album simply because of the way it was recorded, but this would prove to be a factor that allowed fans to feel as if they knew Smith as it remained his signature delivery style down the line. Even as Figure 8’s full-band forays allowed him to widen the scope of his musical ambitions, it still sounds like he’s singing right next to you—voice double-tracked and fragile, even when it’s telling you off. —Elise Soutar

30 years on, I don’t think it’s radical to hold the opinion that Roman Candle, while great, is the “worst” of Elliott Smith’s six albums. It’s certainly the least fleshed out for obvious reasons, given the background of its recording. It’s redeemed by the fact that the songs are strong, even in their skeletal form, as Cavity Search clearly heard. The spareness is a matter of necessity, but you can tell it can bear the weight of dense arrangements—showcasing Smith’s often overlooked technical playing abilities. The only reason we might underrate it now is that we can look to what this seed of insane talent will build to, though the first record introduces thematic concerns and a penchant for melodic complexity that will show up again in subsequent records. Roman Candle, thematically, is all about halves—half-riddles, Irish goodbyes, phone calls where no one says what they really want to say and pleas to not talk about it. Even before his own drug use started, Elliott Smith always focused on dependence, capturing people drifting apart or coming back to things they depend on. I’m sure that reliance strikes further fury into the hearts of those who experience it, leaving them unsure where to turn. There’s an intimacy to the album simply because of the way it was recorded, but this would prove to be a factor that allowed fans to feel as if they knew Smith as it remained his signature delivery style down the line. Even as Figure 8’s full-band forays allowed him to widen the scope of his musical ambitions, it still sounds like he’s singing right next to you—voice double-tracked and fragile, even when it’s telling you off. —Elise Soutar

49. The Grifters: Crappin’ You Negative

Two true stories from the 1990s: First, during a semester abroad, I found a copy of the Grifters’ third album, Crappin’ You Negative, in a small record store in Edinburgh, with a handwritten Post-It declaring them the “greatest band in the world.” Second, I once got a speeding ticket while listening to the superlatively aggressive “Black Fuel Incinerator.” I should have made the band pay. While the lo-fi trend of the early ’90s offered groups like Guided by Voices and Pavement a new way to play classic rock, this Memphis group became the greatest band in the world by plumbing local sources for inspiration, not just the Stax-solid beats but also a beleaguered mood that conveys the blues even if it doesn’t actually sound anything close to the blues. One of the great unsung albums of the decade, Crappin’ You Negative turned decades of Bluff City history into blurry, dirty, ugly, glorious and eloquent rock ’n’ roll. —Stephen M. Deusner

Two true stories from the 1990s: First, during a semester abroad, I found a copy of the Grifters’ third album, Crappin’ You Negative, in a small record store in Edinburgh, with a handwritten Post-It declaring them the “greatest band in the world.” Second, I once got a speeding ticket while listening to the superlatively aggressive “Black Fuel Incinerator.” I should have made the band pay. While the lo-fi trend of the early ’90s offered groups like Guided by Voices and Pavement a new way to play classic rock, this Memphis group became the greatest band in the world by plumbing local sources for inspiration, not just the Stax-solid beats but also a beleaguered mood that conveys the blues even if it doesn’t actually sound anything close to the blues. One of the great unsung albums of the decade, Crappin’ You Negative turned decades of Bluff City history into blurry, dirty, ugly, glorious and eloquent rock ’n’ roll. —Stephen M. Deusner

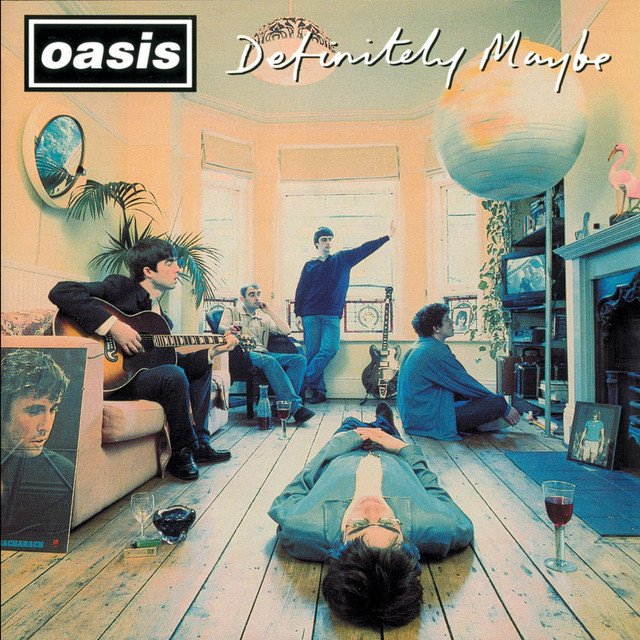

48. Blur: Parklife

A 4x Platinum-certified album in the UK, Parklife is one of the greatest Britpop records ever made, one that certified Blur as part of the genre’s backbone. Songs like “Girls & Boys,” “End of a Century” and “To the End” are great pre-Y2K pop standards that show off Damon Albarn and co.’s budding stardom. If the 1990s were an epoch in the music zeitgeist, then Parklife was the generational catalyst that put them on a pedestal with Oasis and Pulp and, for better or for worse, made the boys’ club of Britpop sound rather ambitious and formidable. —Matt Mitchell

A 4x Platinum-certified album in the UK, Parklife is one of the greatest Britpop records ever made, one that certified Blur as part of the genre’s backbone. Songs like “Girls & Boys,” “End of a Century” and “To the End” are great pre-Y2K pop standards that show off Damon Albarn and co.’s budding stardom. If the 1990s were an epoch in the music zeitgeist, then Parklife was the generational catalyst that put them on a pedestal with Oasis and Pulp and, for better or for worse, made the boys’ club of Britpop sound rather ambitious and formidable. —Matt Mitchell

47. Velvet Crush: Teenage Symphonies to God

Named after how Brian Wilson described Smile, Teenage Symphonies to God is one of the best power pop records of its time, crafted by the Rhode Island trio Velvet Crush with an affinity for the Byrds and Game Theory bubbling at the surface. The album is brimming with top-note songwriting and wields a compassionate, catchy grandiosity that, like all great power pop collections, is ripe with close-to-the-chest sorrow. Listening to songs like “Time Wraps Around You” and “This Life is Killing Me,” it’s clear that Velvet Crush held no qualms about being disciples of the Alex Chilton school of smashingly melodic songcraft, and Teenage Symphonies to God is a work of marvelous timelessness. —Matt Mitchell

Named after how Brian Wilson described Smile, Teenage Symphonies to God is one of the best power pop records of its time, crafted by the Rhode Island trio Velvet Crush with an affinity for the Byrds and Game Theory bubbling at the surface. The album is brimming with top-note songwriting and wields a compassionate, catchy grandiosity that, like all great power pop collections, is ripe with close-to-the-chest sorrow. Listening to songs like “Time Wraps Around You” and “This Life is Killing Me,” it’s clear that Velvet Crush held no qualms about being disciples of the Alex Chilton school of smashingly melodic songcraft, and Teenage Symphonies to God is a work of marvelous timelessness. —Matt Mitchell

46. OutKast: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik

From the very beginning of OutKast’s debut album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, we’re informed that this record is going to be “nothing but king shit.” The vocal intro, titled “Peaches,” comes from the late singer Myrna “Peaches” Crenshaw (not to be confused with Peaches Nisker), setting the scene as she introduces listeners to fresh new Dirty South sounds. The 1990s were a remarkable time for hip-hop, as the early parts of the decade introduced us to the groovy, yet armored West Coast sounds—like those featured on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic—and the East Coast jazzy, conscious musical stylings—namely Nas, with his 1994 debut, Illmatic. Though Dirty South sounds weren’t missing from the landscape, the two coasts had a strong market share within hip-hop. But when OutKast debuted in 1994, they arrived with an ardent mission: to amplify the voices and the art of southern artists. Upon the release of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, the South would soon rise again and again. OutKast’s members—Big Boi and André 3000—had only met each other two years before making their debut album, when they were both only 16 years old. But their musical chemistry quickly proved undeniable. Honing their craft through rap battles at Tri-Cities High School, Dré would drop out by 17 and work multiple jobs before he and Big Boi officially formed the soon-to-be-revered duo. While Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, in its heart-of-hearts, is a reflective record, it never pretends to be a “conscious” album. Rather, it is a homegrown project capturing the nuance and heart of Dré and Big Boi’s hometown of Atlanta. At the foundation of the project is the gangsta lifestyle, especially given that a good portion of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was funded by way of street hustling. But Dré and Big Boi’s mission was always to uplift the ATL area and pave the way for a better future for the city they came up in. —Alex Gonzalez

From the very beginning of OutKast’s debut album Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, we’re informed that this record is going to be “nothing but king shit.” The vocal intro, titled “Peaches,” comes from the late singer Myrna “Peaches” Crenshaw (not to be confused with Peaches Nisker), setting the scene as she introduces listeners to fresh new Dirty South sounds. The 1990s were a remarkable time for hip-hop, as the early parts of the decade introduced us to the groovy, yet armored West Coast sounds—like those featured on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic—and the East Coast jazzy, conscious musical stylings—namely Nas, with his 1994 debut, Illmatic. Though Dirty South sounds weren’t missing from the landscape, the two coasts had a strong market share within hip-hop. But when OutKast debuted in 1994, they arrived with an ardent mission: to amplify the voices and the art of southern artists. Upon the release of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, the South would soon rise again and again. OutKast’s members—Big Boi and André 3000—had only met each other two years before making their debut album, when they were both only 16 years old. But their musical chemistry quickly proved undeniable. Honing their craft through rap battles at Tri-Cities High School, Dré would drop out by 17 and work multiple jobs before he and Big Boi officially formed the soon-to-be-revered duo. While Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, in its heart-of-hearts, is a reflective record, it never pretends to be a “conscious” album. Rather, it is a homegrown project capturing the nuance and heart of Dré and Big Boi’s hometown of Atlanta. At the foundation of the project is the gangsta lifestyle, especially given that a good portion of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was funded by way of street hustling. But Dré and Big Boi’s mission was always to uplift the ATL area and pave the way for a better future for the city they came up in. —Alex Gonzalez

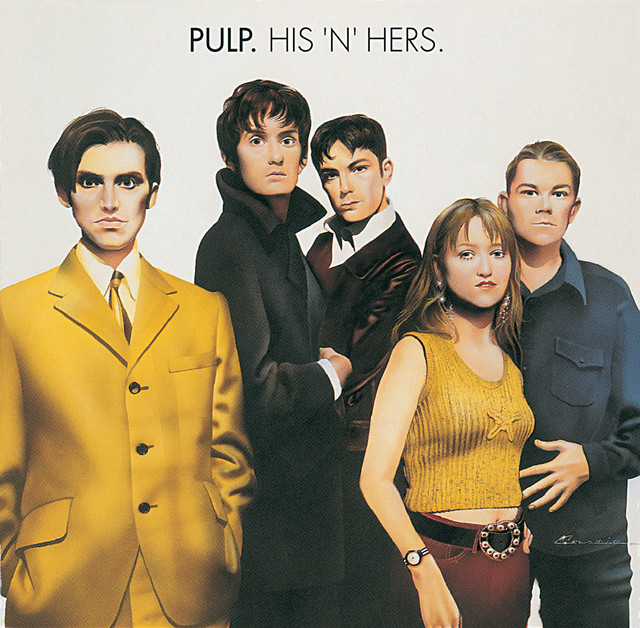

45. Pulp: His ‘n’ Hers

In hindsight, there are few albums I have experienced listening to where a male-fronted band writes about sex with little concern for masculine tropes. There’s not much ego to be found in the scenes Joe Cocker paints of the bedroom. Take “She’s A Lady,” where instead of the usual cliches of a woman pining after an ex, Cocker embodies that role, struggling to carry on in the absence of a lover: “Whilst you were gone, I got along, I didn’t die, I carried on. Oh yeah, you’ve got to hold me tight, so I can make it through the night.” It subverts the narrative to where the woman clearly has the power in this situation. The way Cocker treats the women in his lyrics is with a mixture of instinctual, ravaging horniness but also a refreshing intimacy where women aren’t throwaway objects—instead he wants to “hold you forever” in “Acrylic Afternoons.” The extra touches of embrace and femininity found throughout Cocker’s descriptions of sex on His ‘n’ Hers gave pop music in the ‘90’s a refreshingly anti-masculine perspective that spoke of the power either sex could have in the bedroom, a space where ego shouldn’t have to matter. —Matty Pywell

In hindsight, there are few albums I have experienced listening to where a male-fronted band writes about sex with little concern for masculine tropes. There’s not much ego to be found in the scenes Joe Cocker paints of the bedroom. Take “She’s A Lady,” where instead of the usual cliches of a woman pining after an ex, Cocker embodies that role, struggling to carry on in the absence of a lover: “Whilst you were gone, I got along, I didn’t die, I carried on. Oh yeah, you’ve got to hold me tight, so I can make it through the night.” It subverts the narrative to where the woman clearly has the power in this situation. The way Cocker treats the women in his lyrics is with a mixture of instinctual, ravaging horniness but also a refreshing intimacy where women aren’t throwaway objects—instead he wants to “hold you forever” in “Acrylic Afternoons.” The extra touches of embrace and femininity found throughout Cocker’s descriptions of sex on His ‘n’ Hers gave pop music in the ‘90’s a refreshingly anti-masculine perspective that spoke of the power either sex could have in the bedroom, a space where ego shouldn’t have to matter. —Matty Pywell

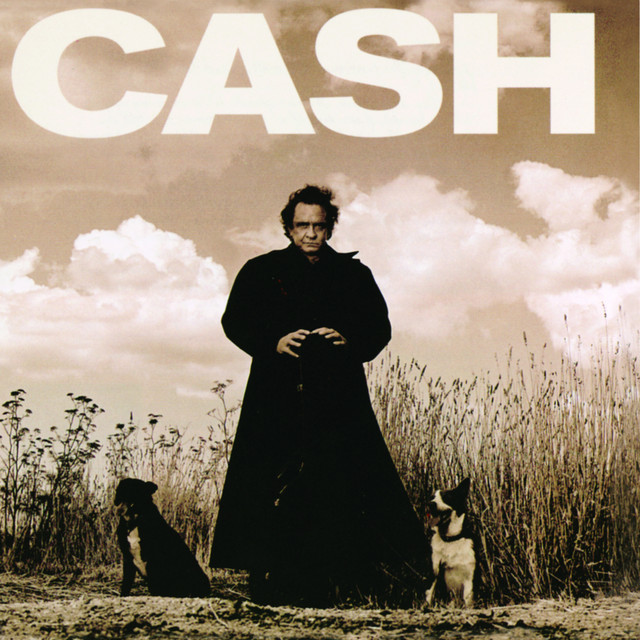

44. Johnny Cash: American Recordings

30 years have passed since Johnny Cash dropped the first installment of his American Recordings series on an unexpecting public. Harder to believe is that the Man in Black has already been at his Maker’s side for two of those decades. When hip-hop/hard rock producer Rick Rubin first approached Cash about recording for American Recordings, the aging country icon was an artist without a label or creative purpose. Together, their unlikely partnership yielded a string of inspired, award-winning albums that once again made Cash a vital voice in contemporary music. Looking back, we understand that these recordings did more than just resurrect Cash’s career; they sustained the man himself through serious illness, the death of his beloved wife, June Carter Cash, and the toll of his own final days. These songs, mostly covers handpicked by Cash and Rubin, deal in remorse, redemption and salvation in this life and the next. —Matt Melis

30 years have passed since Johnny Cash dropped the first installment of his American Recordings series on an unexpecting public. Harder to believe is that the Man in Black has already been at his Maker’s side for two of those decades. When hip-hop/hard rock producer Rick Rubin first approached Cash about recording for American Recordings, the aging country icon was an artist without a label or creative purpose. Together, their unlikely partnership yielded a string of inspired, award-winning albums that once again made Cash a vital voice in contemporary music. Looking back, we understand that these recordings did more than just resurrect Cash’s career; they sustained the man himself through serious illness, the death of his beloved wife, June Carter Cash, and the toll of his own final days. These songs, mostly covers handpicked by Cash and Rubin, deal in remorse, redemption and salvation in this life and the next. —Matt Melis

43. Stone Temple Pilots: Purple

Purple the second Stone Temple Pilots album, was so beloved that it didn’t just debut at #1 on the Billboard 200, but it went on to sell over six million copies (including 250,000 units in its first week). Thanks to tracks like “Vasoline” and “Interstate Love Song,” Scott Weiland, Dean and Robert DeLeo and Eric Kretz turned the rock world upside down with their impressionistic, radio-friendly collision of pyschedelia, grunge and heavy, spine-tingling rock ‘n’ roll. Deeper cuts, like “Big Empty,” “Pretty Penny” and “Unglued,” showcased the band’s formula for perfection: Dean and Robert’s no-fuss songcraft and Weiland’s unbelievable penchant for warping STP’s music inside out with his deep, versatile baritone vocal. —Matt Mitchell

Purple the second Stone Temple Pilots album, was so beloved that it didn’t just debut at #1 on the Billboard 200, but it went on to sell over six million copies (including 250,000 units in its first week). Thanks to tracks like “Vasoline” and “Interstate Love Song,” Scott Weiland, Dean and Robert DeLeo and Eric Kretz turned the rock world upside down with their impressionistic, radio-friendly collision of pyschedelia, grunge and heavy, spine-tingling rock ‘n’ roll. Deeper cuts, like “Big Empty,” “Pretty Penny” and “Unglued,” showcased the band’s formula for perfection: Dean and Robert’s no-fuss songcraft and Weiland’s unbelievable penchant for warping STP’s music inside out with his deep, versatile baritone vocal. —Matt Mitchell

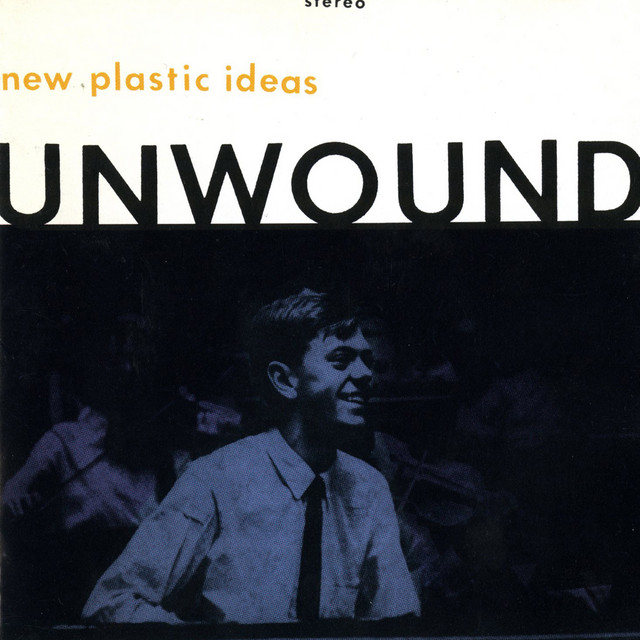

42. Unwound: New Plastic Ideas

New Plastic Ideas, the second Unwound album, is full of oddities without breaking the ground completely. It’s a dark, strangely-metered record with a big, bold sound and gutteral contrasts of light and dark. The guitar riffs punish while Justin Trosper’s blitzkreig vocal pushes the chaos across a tightrope of dense anger. Unwound sound like a Joy Division-meets-Fugazi type of outfit, conjuring dissonance while barking at a harrowing, menacing type of theatricality. Tracks like “Abstraktions” and “All Souls Day” are cresting fits of kinetic, marauding noise and massive, furious hooks. New Plastic Ideas is blackened yet full of grace—a juxtaposition Unwound pull off in classic fashion. —Matt Mitchell

New Plastic Ideas, the second Unwound album, is full of oddities without breaking the ground completely. It’s a dark, strangely-metered record with a big, bold sound and gutteral contrasts of light and dark. The guitar riffs punish while Justin Trosper’s blitzkreig vocal pushes the chaos across a tightrope of dense anger. Unwound sound like a Joy Division-meets-Fugazi type of outfit, conjuring dissonance while barking at a harrowing, menacing type of theatricality. Tracks like “Abstraktions” and “All Souls Day” are cresting fits of kinetic, marauding noise and massive, furious hooks. New Plastic Ideas is blackened yet full of grace—a juxtaposition Unwound pull off in classic fashion. —Matt Mitchell

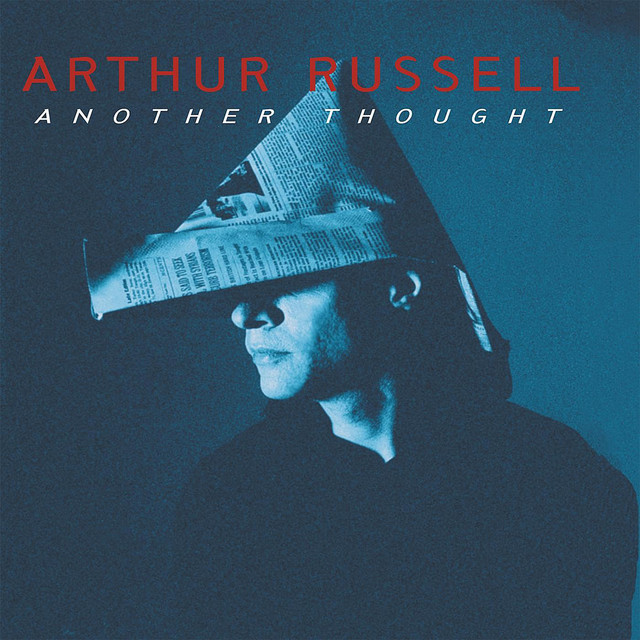

41. Arthur Russell: Another Thought

Released two years after the cellist/composer’s death from AIDS in 1992, Another Thought is elegiac, peculiar and introductory all at once—reminding listeners of Arthur Russell’s history as a disco producer along with his more avant-garde, experimental curiosities. Memory reverberates across Russell’s epitaph, as he combines Indian percussion, Black Ark horns, hand instruments and vocal distortion into a fascinating spectrum of timeless, otherworldly mischief. But even in its buoyancy, the record is textbook minimalism. Another Thought isn’t World of Echo or Love is Overtaking Me, but it should never be considered that way. It’s a compilation record memorializing a prescient affinity for pop structures in their barest forms—delivered through demo tapes, just a handful of the some couple-thousand Russell left behind. “In the Light of the Miracle” very well be one of the greatest songs Russell ever wrote; “A Little Lost” is certainly one of his sweetest. —Matt Mitchell

Released two years after the cellist/composer’s death from AIDS in 1992, Another Thought is elegiac, peculiar and introductory all at once—reminding listeners of Arthur Russell’s history as a disco producer along with his more avant-garde, experimental curiosities. Memory reverberates across Russell’s epitaph, as he combines Indian percussion, Black Ark horns, hand instruments and vocal distortion into a fascinating spectrum of timeless, otherworldly mischief. But even in its buoyancy, the record is textbook minimalism. Another Thought isn’t World of Echo or Love is Overtaking Me, but it should never be considered that way. It’s a compilation record memorializing a prescient affinity for pop structures in their barest forms—delivered through demo tapes, just a handful of the some couple-thousand Russell left behind. “In the Light of the Miracle” very well be one of the greatest songs Russell ever wrote; “A Little Lost” is certainly one of his sweetest. —Matt Mitchell

40. Victoria Williams: Loose

Victoria Williams’s biggest moment in the sun came through 1993’s Sweet Relief album, where her songs were covered by Lou Reed, Pearl Jam, Soul Asylum and The Jayhawks to help raise money for health costs after she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. One of those songs, “Crazy Mary,” would appear the next year on Loose, her third and best full-length. On it, she also sings a duet with her future husband, The Jayhawks’ Mark Olson, “When We Sing Together.” There’s a tenderness and fragility to these tracks that fits perfectly with her idiosyncratic lyrics, filled with an emotional depth, whether she’s singing about her dog, her grandfather, her crazy childhood neighbor or her soon-to-be husband—or just letting you know You R Loved. —Josh Jackson

Victoria Williams’s biggest moment in the sun came through 1993’s Sweet Relief album, where her songs were covered by Lou Reed, Pearl Jam, Soul Asylum and The Jayhawks to help raise money for health costs after she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. One of those songs, “Crazy Mary,” would appear the next year on Loose, her third and best full-length. On it, she also sings a duet with her future husband, The Jayhawks’ Mark Olson, “When We Sing Together.” There’s a tenderness and fragility to these tracks that fits perfectly with her idiosyncratic lyrics, filled with an emotional depth, whether she’s singing about her dog, her grandfather, her crazy childhood neighbor or her soon-to-be husband—or just letting you know You R Loved. —Josh Jackson

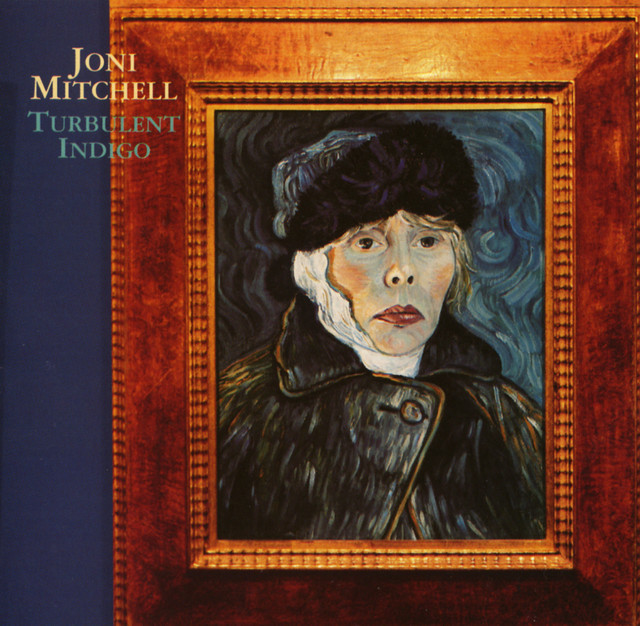

39. Joni Mitchell: Turbulent Indigo

On the cover of Turbulent Indigo, Joni Mitchell styles herself as a Vincent Van Gogh type. The title track is about the tragic painter, but it’s also about the debts artists settle through their work. A good metaphor for Joni’s Reprise comeback, “Turbulent Indigo” is a measurement of access—a question of where art goes when the artist is forbidden such intimacies. “Brash fields crude crows in a scary sky, in a gold frame roped off,” Joni sings. “Tourists guided by tourists talking about the madhouse, talking about the ear. The madman hangs in fancy homes they wouldn’t let him near!” Joni, ever the provocateur, is famous for having a canon of self-portraits—images that blur the self and the world around us into an intertwined, messy convex mirror. The truth bends toward the light; the cruelty inching onward. Dylan Thomas once wrote: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light”; Joni Mitchell once wrote: “I was awaited like the rain.” And she sang those words to a crowd of thousands last month, her tongue wrapping around “I’ve lost all taste for life” like a lie. Turbulent Indigo, arched into the thesis of “Sunny Sunday” and its gun-toting protagonist who sits in the darkness of her own home, is not about redemption. No, Joni Mitchell’s 15th album is about how the freeway hisses now that the canyons have tumbled into the horizon—how borderlines are barbed wire fences and it is up to us to make a mess in the dumb luck of our collective living. She has soundtracked each of our lives, through the grief and through the glow, for almost 60 years, outliving everything she dreaded and everything she feared would come true. In the wake of the atrocity that plagues Turbulent Indigo, maybe we ought to take a moment to relish the splendors of survival. As Joni demands of us on “Yvette in English”: “Please, have this little bit of instant bliss.” —Matt Mitchell

On the cover of Turbulent Indigo, Joni Mitchell styles herself as a Vincent Van Gogh type. The title track is about the tragic painter, but it’s also about the debts artists settle through their work. A good metaphor for Joni’s Reprise comeback, “Turbulent Indigo” is a measurement of access—a question of where art goes when the artist is forbidden such intimacies. “Brash fields crude crows in a scary sky, in a gold frame roped off,” Joni sings. “Tourists guided by tourists talking about the madhouse, talking about the ear. The madman hangs in fancy homes they wouldn’t let him near!” Joni, ever the provocateur, is famous for having a canon of self-portraits—images that blur the self and the world around us into an intertwined, messy convex mirror. The truth bends toward the light; the cruelty inching onward. Dylan Thomas once wrote: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light”; Joni Mitchell once wrote: “I was awaited like the rain.” And she sang those words to a crowd of thousands last month, her tongue wrapping around “I’ve lost all taste for life” like a lie. Turbulent Indigo, arched into the thesis of “Sunny Sunday” and its gun-toting protagonist who sits in the darkness of her own home, is not about redemption. No, Joni Mitchell’s 15th album is about how the freeway hisses now that the canyons have tumbled into the horizon—how borderlines are barbed wire fences and it is up to us to make a mess in the dumb luck of our collective living. She has soundtracked each of our lives, through the grief and through the glow, for almost 60 years, outliving everything she dreaded and everything she feared would come true. In the wake of the atrocity that plagues Turbulent Indigo, maybe we ought to take a moment to relish the splendors of survival. As Joni demands of us on “Yvette in English”: “Please, have this little bit of instant bliss.” —Matt Mitchell

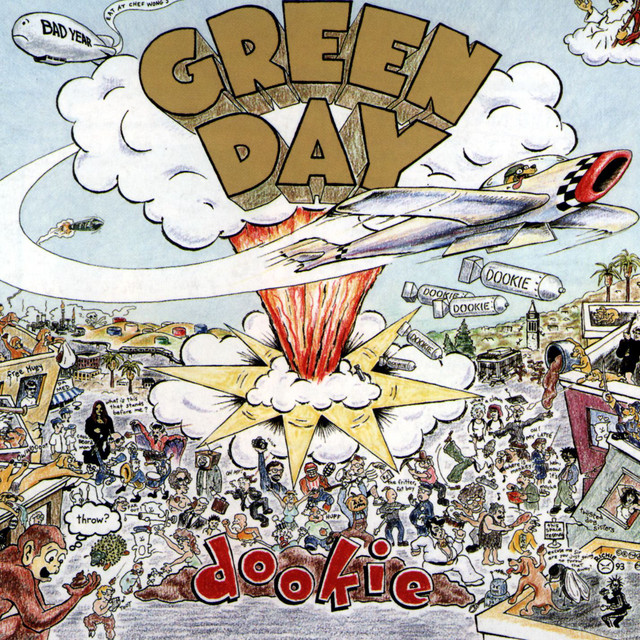

38. Low: I Could Live in Hope

In an era when grunge’s distortion-heavy angst dominated alternative music, Low’s I Could Live in Hope emerged like a whispered prayer in 1994, creating space for contemplation in an increasingly noisy world. The Duluth, Minnesota trio’s debut album didn’t just introduce slowcore to the indie lexicon (somewhat accidentally, given how the band has gone on record as disliking the term)—it also redefined what emotional intensity could sound like. The album’s power lies in its radical restraint, its ability to transform limitation into transcendence. While their contemporaries were releasing aggressive statements like Nine Inch Nails’ “March of the Pigs” and Green Day’s Dookie, Alan Sparhawk’s spectral guitar work, Mimi Parker’s barely-there percussion, and John Nichols’s patient basslines create vast emotional landscapes where silence becomes as important as sound. Sparhawk and Parker’s harmonies float like frost on a Minnesota morning, particularly on the album opener “Words,” where their voices intertwine to create something approaching the divine. Songs like “Slide,” featuring Parker’s heart-rending soprano, demonstrate how devastation can be conveyed without ever raising above a near whisper. In the wake of Parker’s passing in 2022, these songs have taken on an even more profound resonance, serving as a testament to the power of finding light in darkness. Each listen reveals new depths in its sparse arrangements, like discovering constellations in that starless winter sky the band so perfectly evoked. Even the album’s title has proven prophetic over the past three decades, embodying the band’s aesthetic of understated beauty and quiet resilience. It’s this underlying thread of optimism, however faint, that makes the record just as important today as it was 30 years ago. As Sparhawk himself once noted, “Even in the darkest song, there’s a spark of hope, because someone’s writing this down, making sense of it, trying to communicate.” In a world that seems to grow louder and more chaotic with each passing year, I Could Live in Hope remains a vital reminder that sometimes the quietest voices speak the loudest truths. —Casey Epstein-Gross

In an era when grunge’s distortion-heavy angst dominated alternative music, Low’s I Could Live in Hope emerged like a whispered prayer in 1994, creating space for contemplation in an increasingly noisy world. The Duluth, Minnesota trio’s debut album didn’t just introduce slowcore to the indie lexicon (somewhat accidentally, given how the band has gone on record as disliking the term)—it also redefined what emotional intensity could sound like. The album’s power lies in its radical restraint, its ability to transform limitation into transcendence. While their contemporaries were releasing aggressive statements like Nine Inch Nails’ “March of the Pigs” and Green Day’s Dookie, Alan Sparhawk’s spectral guitar work, Mimi Parker’s barely-there percussion, and John Nichols’s patient basslines create vast emotional landscapes where silence becomes as important as sound. Sparhawk and Parker’s harmonies float like frost on a Minnesota morning, particularly on the album opener “Words,” where their voices intertwine to create something approaching the divine. Songs like “Slide,” featuring Parker’s heart-rending soprano, demonstrate how devastation can be conveyed without ever raising above a near whisper. In the wake of Parker’s passing in 2022, these songs have taken on an even more profound resonance, serving as a testament to the power of finding light in darkness. Each listen reveals new depths in its sparse arrangements, like discovering constellations in that starless winter sky the band so perfectly evoked. Even the album’s title has proven prophetic over the past three decades, embodying the band’s aesthetic of understated beauty and quiet resilience. It’s this underlying thread of optimism, however faint, that makes the record just as important today as it was 30 years ago. As Sparhawk himself once noted, “Even in the darkest song, there’s a spark of hope, because someone’s writing this down, making sense of it, trying to communicate.” In a world that seems to grow louder and more chaotic with each passing year, I Could Live in Hope remains a vital reminder that sometimes the quietest voices speak the loudest truths. —Casey Epstein-Gross

37. Beastie Boys: Ill Communication

Few lead singles in the 1990s were as definitive as “Sabotage,” one of the greatest rap-rock songs ever created. But Ill Communication, the Beastie Boys’ best album since Paul’s Boutique, was so much more than “Sabotage”—songs like “Root Down,” “Get It Together” and “Sure Shot” were abrasive, hell-raising, New York Knicks-shouting emblems of a trend-setting, anarchist rap finesse executed without flaw by Ad-Rock, MCA and Mike D. Ill Communication featured guest verses from Q-Tip and Biz Markie, and the album cracked open the floodgates with the trio’s personalities coming to a boil: MCA, the spiritual emcee; Mike D, the working class messiah; Ad-Rock, the Dick Hyman- and Vaughn Bode-citing originator of Gen-X verbiage. Few NYC albums are as straight-up or as memorable as em>Ill Communication—a classic that wasn’t instant, but exists as such now. The inverse to the city’s mirage of jazz-rap, the Beastie Boys’ fourth album knocked down—and rebuilt—every wall the trio put up, thumping through record scratches and basslines everyone and your mother can recognize. —Matt Mitchell

Few lead singles in the 1990s were as definitive as “Sabotage,” one of the greatest rap-rock songs ever created. But Ill Communication, the Beastie Boys’ best album since Paul’s Boutique, was so much more than “Sabotage”—songs like “Root Down,” “Get It Together” and “Sure Shot” were abrasive, hell-raising, New York Knicks-shouting emblems of a trend-setting, anarchist rap finesse executed without flaw by Ad-Rock, MCA and Mike D. Ill Communication featured guest verses from Q-Tip and Biz Markie, and the album cracked open the floodgates with the trio’s personalities coming to a boil: MCA, the spiritual emcee; Mike D, the working class messiah; Ad-Rock, the Dick Hyman- and Vaughn Bode-citing originator of Gen-X verbiage. Few NYC albums are as straight-up or as memorable as em>Ill Communication—a classic that wasn’t instant, but exists as such now. The inverse to the city’s mirage of jazz-rap, the Beastie Boys’ fourth album knocked down—and rebuilt—every wall the trio put up, thumping through record scratches and basslines everyone and your mother can recognize. —Matt Mitchell

36. R.E.M.: Monster

“A new sound well-removed from the sickly-sweet tones of the smash hit ‘Shiny Happy People.’” Those are the words that Australian TV host Brian Armstrong used to describe R.E.M.’s 1994 album Monster a few months after its release. Armstrong may have been laying it on a little thick—“Shiny Happy People,” after all, was written to be sappy on purpose—but it’s not like he wasn’t telling the truth, or even saying anything the band didn’t agree with. At the time, millions upon millions of listeners associated R.E.M. with a tameness that didn’t accurately reflect everything the band had to offer. Monster, the band’s ninth studio full-length, marked a decisive turn away from the mellow, downtempo vibe of its previous two albums, 1991’s Out of Time and 1992’s Automatic for the People, both of which became huge commercial successes, effectively ending R.E.M.’s position as standard bearers of the alternative underground movement they had emerged from. Monster amounts to more than a “return to roots” kind of effort—if it can even be viewed that way at all. In a career that spans 18 full-length titles over a 28-year stretch, Monster, in some respects, stands apart from the rest of the R.E.M. catalog like a sore thumb: a blinking, neon-hued sore thumb that casts its own distinct glow. Nevertheless, the album also manages to reflect the band’s essence in spite of itself. R.E.M. had actually grown so proficient at writing anthemic singalong choruses by that point that iconic singles such as “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” and “Crush with Eyeliner” partially mask the tangled contradictions and undercurrent of strangeness that thread through all but one of the Monster’s songs. Overall, the album meshes garage-rock abandon with arena-sized posturing, simplicity with experimentation, earnestness with irony and a pointedly dark edge that somehow manages to come off as frivolous. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

“A new sound well-removed from the sickly-sweet tones of the smash hit ‘Shiny Happy People.’” Those are the words that Australian TV host Brian Armstrong used to describe R.E.M.’s 1994 album Monster a few months after its release. Armstrong may have been laying it on a little thick—“Shiny Happy People,” after all, was written to be sappy on purpose—but it’s not like he wasn’t telling the truth, or even saying anything the band didn’t agree with. At the time, millions upon millions of listeners associated R.E.M. with a tameness that didn’t accurately reflect everything the band had to offer. Monster, the band’s ninth studio full-length, marked a decisive turn away from the mellow, downtempo vibe of its previous two albums, 1991’s Out of Time and 1992’s Automatic for the People, both of which became huge commercial successes, effectively ending R.E.M.’s position as standard bearers of the alternative underground movement they had emerged from. Monster amounts to more than a “return to roots” kind of effort—if it can even be viewed that way at all. In a career that spans 18 full-length titles over a 28-year stretch, Monster, in some respects, stands apart from the rest of the R.E.M. catalog like a sore thumb: a blinking, neon-hued sore thumb that casts its own distinct glow. Nevertheless, the album also manages to reflect the band’s essence in spite of itself. R.E.M. had actually grown so proficient at writing anthemic singalong choruses by that point that iconic singles such as “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” and “Crush with Eyeliner” partially mask the tangled contradictions and undercurrent of strangeness that thread through all but one of the Monster’s songs. Overall, the album meshes garage-rock abandon with arena-sized posturing, simplicity with experimentation, earnestness with irony and a pointedly dark edge that somehow manages to come off as frivolous. —Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

35. Guided By Voices: Bee Thousand

GBV fanatics will argue over which album is best until humanity dies out, but 1994’s Bee Thousand is clearly the critical choice, and the record that broke the band to a wider audience. Bob Pollard’s four-track epic kicks out a sequence of would-be hits that rival the best work of his idols, mashing the pop hooks of The Beatles, the titanic riffs of The Who and the arty, noisy brevity of Wire into an insistent lo-fi masterpiece. It’s a crash course on rock history from one of the best songwriters the world will ever see. —Garrett Martin

GBV fanatics will argue over which album is best until humanity dies out, but 1994’s Bee Thousand is clearly the critical choice, and the record that broke the band to a wider audience. Bob Pollard’s four-track epic kicks out a sequence of would-be hits that rival the best work of his idols, mashing the pop hooks of The Beatles, the titanic riffs of The Who and the arty, noisy brevity of Wire into an insistent lo-fi masterpiece. It’s a crash course on rock history from one of the best songwriters the world will ever see. —Garrett Martin

34. Tom Petty: Wildflowers

Unconfined, Tom Petty brought a whole lot of heart into the songs of Wildflowers. The album, Petty’s second solo record following two decades of recording with the Heartbreakers (though many of them are featured on it), stands as a glimmering standout of folk-rock brilliance in his discography—one he referred to as his pet project, a career highlight. The title track’s declaration, “you belong somewhere you feel free,” is a motto for the record’s creation, crafted with longtime bandmates and producer Rick Rubin during a period of pure musical clarity. —Annie Nickoloff

Unconfined, Tom Petty brought a whole lot of heart into the songs of Wildflowers. The album, Petty’s second solo record following two decades of recording with the Heartbreakers (though many of them are featured on it), stands as a glimmering standout of folk-rock brilliance in his discography—one he referred to as his pet project, a career highlight. The title track’s declaration, “you belong somewhere you feel free,” is a motto for the record’s creation, crafted with longtime bandmates and producer Rick Rubin during a period of pure musical clarity. —Annie Nickoloff

33. Sunny Day Real Estate: Diary

Diary is still a perfect storm of a record. Jeremy Enigk’s voice elegantly cradles his most tender words in one moment, before charging into wrought screams of pure passion against Dan Hoerner’s harmonies. Hoerner’s riffs grip with an urgency and force that’s matched by William Goldsmith’s precision behind the drums, each snare hit an emphatic punch that sucks the air out of the room, and former bassist Nate Mendel adds a whole melodic dimension of his own, as if creating ‘90s rock’s answer to John Entwistle. The emphasis on patience and dynamics makes each refrain’s emergence all the more arresting—when a chorus hits on Diary, it explodes. The refrains on “Seven” and “In Circles” and “The Blankets Were the Stairs” wallop like a sandbag dropped on your skull, the sheer force and emotion put into their every syllable rendering them anthemic on arrival. —Natalie Marlin

Diary is still a perfect storm of a record. Jeremy Enigk’s voice elegantly cradles his most tender words in one moment, before charging into wrought screams of pure passion against Dan Hoerner’s harmonies. Hoerner’s riffs grip with an urgency and force that’s matched by William Goldsmith’s precision behind the drums, each snare hit an emphatic punch that sucks the air out of the room, and former bassist Nate Mendel adds a whole melodic dimension of his own, as if creating ‘90s rock’s answer to John Entwistle. The emphasis on patience and dynamics makes each refrain’s emergence all the more arresting—when a chorus hits on Diary, it explodes. The refrains on “Seven” and “In Circles” and “The Blankets Were the Stairs” wallop like a sandbag dropped on your skull, the sheer force and emotion put into their every syllable rendering them anthemic on arrival. —Natalie Marlin

32. Stereolab: Mars Audiac Quintet

I don’t know what the best Stereolab album is, but I think Mars Audiac Quintet would make a very good choice in such a discussion. It was the English-French pop-rock band’s third album upon its release, following the very good Transient Random-Noise Bursts with Announcements and transforming Laetitia Sadier, Tim Gane, Mary Hansen, Sean O’Hahan, Andy Ramsay, Katharine Gifford and Duncan Brown into the best space age pop band of all time. Stereolab wasn’t just elevator music anymore; they were originators of a timeless compartment of rock ‘n’ roll that would, in due time, careen straight into hypnagogic, subversive, theory-motivated soundscapes. “Wow and Flutter,” “Ping Pong” and “Three-Dee Melodie” sound as distressed as they do euphoric, pinned forever onto the shirt collar of indie pop. Stereolab sang brightly about anti-patriotic, anti-war, anti-capitalist liberation. Death, in the band’s vocabulary, was inevitable, for both the man and the company. Cynicism has never sounded so dreamy. —Matt Mitchell

I don’t know what the best Stereolab album is, but I think Mars Audiac Quintet would make a very good choice in such a discussion. It was the English-French pop-rock band’s third album upon its release, following the very good Transient Random-Noise Bursts with Announcements and transforming Laetitia Sadier, Tim Gane, Mary Hansen, Sean O’Hahan, Andy Ramsay, Katharine Gifford and Duncan Brown into the best space age pop band of all time. Stereolab wasn’t just elevator music anymore; they were originators of a timeless compartment of rock ‘n’ roll that would, in due time, careen straight into hypnagogic, subversive, theory-motivated soundscapes. “Wow and Flutter,” “Ping Pong” and “Three-Dee Melodie” sound as distressed as they do euphoric, pinned forever onto the shirt collar of indie pop. Stereolab sang brightly about anti-patriotic, anti-war, anti-capitalist liberation. Death, in the band’s vocabulary, was inevitable, for both the man and the company. Cynicism has never sounded so dreamy. —Matt Mitchell

31. Hootie & the Blowfish: Cracked Rear View

In modern times, Cracked Rear View may just be the most underloved best-selling album of all time. It sold over 20 million units, yet it’s largely absent from most 1990s-centric conversations. Why? Hootie & the Blowfish positively cooked on this LP, and “Only Wanna Be With You” is, 30 years later, one of the coolest-sounding rock songs of its generation. Darius Rucker would make a leap to country in the 2000s, but his legacy was etched in stone in 1994 when he and his band (Mark Bryan, Dean Felber, Soni Sonefeld) ran circles around the music industry without innovating it one iota. Cracked Rear View is just phenomenal and full of unforgettable hooks from start to end, falling someplace between John Mellencamp’s heartland style and the Counting Crows’ accessible, alternative guise. Maybe Rucker was meant to be a country singer all along, as his one-of-a-kind voice amplifies “Time” and “Drowning” into statement pieces. Hootie & the Blowfish would win a Grammy for “Let Her Cry” and also take home the Best New Artist hardware, and Cracked Rear View was so awesome that even David Crosby featured on it, singing back-up vocals on “Hold My Hand.” Most important of all, Hootie & the Blowfish’s debut album punctured through the uncertain noise of a post-Nirvana landscape with a collection of sharp, no-nonsense and feel-good roots rock built to last. —Matt Mitchell

In modern times, Cracked Rear View may just be the most underloved best-selling album of all time. It sold over 20 million units, yet it’s largely absent from most 1990s-centric conversations. Why? Hootie & the Blowfish positively cooked on this LP, and “Only Wanna Be With You” is, 30 years later, one of the coolest-sounding rock songs of its generation. Darius Rucker would make a leap to country in the 2000s, but his legacy was etched in stone in 1994 when he and his band (Mark Bryan, Dean Felber, Soni Sonefeld) ran circles around the music industry without innovating it one iota. Cracked Rear View is just phenomenal and full of unforgettable hooks from start to end, falling someplace between John Mellencamp’s heartland style and the Counting Crows’ accessible, alternative guise. Maybe Rucker was meant to be a country singer all along, as his one-of-a-kind voice amplifies “Time” and “Drowning” into statement pieces. Hootie & the Blowfish would win a Grammy for “Let Her Cry” and also take home the Best New Artist hardware, and Cracked Rear View was so awesome that even David Crosby featured on it, singing back-up vocals on “Hold My Hand.” Most important of all, Hootie & the Blowfish’s debut album punctured through the uncertain noise of a post-Nirvana landscape with a collection of sharp, no-nonsense and feel-good roots rock built to last. —Matt Mitchell

30. R.L. Burnside: Too Bad Jim

Mississippi bluesman R.L. Burnside was born in 1926, but his first record, Sound Machine Groove, didn’t come out until 1981. He made 12 LPs before passing away in 2005, but few are stronger than his 1994 effort, Too Bad Jim. A disciple of John Lee Hooker, Burnside was at his most comfortable when he was repeating his own styles—both instrumentally and vocally. Too Bad Jim, a marvel of the fife-and-drum blues found in North Mississippi, is expressive and eclectic—a strong convergence of electric and acoustic guitar-playing centered around droning, 12- and 16-bar blues patterns that riff through hill country and Delta schemes and contour beneath the pulse of Burnside’s slide. Tracks like “Shake ‘Em on Down,” “Old Black Mattie” and “Peaches” are withered and juke-joint-ready. Arriving in the wake of Stevie Ray Vaughn’s flashy, white-washed blues renaissance, R.L. Burnside brought a swing-and-stamp, entrancing technique back into focus. Too Bad Jim is the kind of record that exists in every lifetime beyond this one. —Matt Mitchell

Mississippi bluesman R.L. Burnside was born in 1926, but his first record, Sound Machine Groove, didn’t come out until 1981. He made 12 LPs before passing away in 2005, but few are stronger than his 1994 effort, Too Bad Jim. A disciple of John Lee Hooker, Burnside was at his most comfortable when he was repeating his own styles—both instrumentally and vocally. Too Bad Jim, a marvel of the fife-and-drum blues found in North Mississippi, is expressive and eclectic—a strong convergence of electric and acoustic guitar-playing centered around droning, 12- and 16-bar blues patterns that riff through hill country and Delta schemes and contour beneath the pulse of Burnside’s slide. Tracks like “Shake ‘Em on Down,” “Old Black Mattie” and “Peaches” are withered and juke-joint-ready. Arriving in the wake of Stevie Ray Vaughn’s flashy, white-washed blues renaissance, R.L. Burnside brought a swing-and-stamp, entrancing technique back into focus. Too Bad Jim is the kind of record that exists in every lifetime beyond this one. —Matt Mitchell

29. Alan Jackson: Who I Am

By the time Alan Jackson released Who I Am in June 1994, he’d already made three albums and transformed an era of country music that only gets more perfect with every passing decade. A Lot About Livin’ (and a Little ‘Bout Love) established Jackson as a country and blues powerhouse two years prior, all thanks to a single called “Chattahoochee” that can still knock the door off the hinges at any function around. Who I Am was a blockbuster, though, with four #1 singles (“Summertime Blues,” “Gone Country,” “Livin’ on Love” and “I Don’t Even Know Your Name”) and a nice Platinum certification from the RIAA. The record, rivaled in 1994 only by Tim McGraw’s Not a Moment Too Soon, set a precedent of success that would make Alan Jackson immortal. “Gone Country” and “Livin’ on Love” especially are two of the greatest country songs of the 1990s, and Who I Am was, arguably, the single best release genre in-between the decade’s strong bookends (Garth Brooks’s No Fences and Shania Twain’s Come On Over). If you’re like me and you grew up on country music radio, Who I Am is, sometimes, as biblical as the Holy Bible itself. —Matt Mitchell

By the time Alan Jackson released Who I Am in June 1994, he’d already made three albums and transformed an era of country music that only gets more perfect with every passing decade. A Lot About Livin’ (and a Little ‘Bout Love) established Jackson as a country and blues powerhouse two years prior, all thanks to a single called “Chattahoochee” that can still knock the door off the hinges at any function around. Who I Am was a blockbuster, though, with four #1 singles (“Summertime Blues,” “Gone Country,” “Livin’ on Love” and “I Don’t Even Know Your Name”) and a nice Platinum certification from the RIAA. The record, rivaled in 1994 only by Tim McGraw’s Not a Moment Too Soon, set a precedent of success that would make Alan Jackson immortal. “Gone Country” and “Livin’ on Love” especially are two of the greatest country songs of the 1990s, and Who I Am was, arguably, the single best release genre in-between the decade’s strong bookends (Garth Brooks’s No Fences and Shania Twain’s Come On Over). If you’re like me and you grew up on country music radio, Who I Am is, sometimes, as biblical as the Holy Bible itself. —Matt Mitchell

28. Veruca Salt: American Thighs

Few bands on this list can be felt so strongly in 2024, but Veruca Salt remains an apt blueprint for the modern rock age—thanks to just how good and immortal “Seether” is. The Chicago band—singer/guitarists Nina Gordon and Louise Post, backed by Steve Lack and Jim Shapiro—formed just two years earlier but had figured out their sound right away. The crux of the AC/DC-inspired American Thighs, their debut for Minty Fresh, is damn heady guitar playing, mountains of distortion and a catchiness most grunge-adjacent, hard-rocking albums were short on at the time. Heaviness was a weapon for Veruca Salt, who crafted sugary, punishing licks on “Number One Blind,” “Victrola” and “Spiderman ‘79.” American Thighs is an album built on contradictions, existing as this infectious tapestry of brutality and innocence collapsing into each other (Veruca Salt is, of course, a character in a Roald Dahl novel). Gordon and Post’s harmonies remain pivotal 30 years later, and you can hear them in the work of active bands like Horsegirl, Wednesday, Soccer Mommy, Momma and so many more. —Matt Mitchell

Few bands on this list can be felt so strongly in 2024, but Veruca Salt remains an apt blueprint for the modern rock age—thanks to just how good and immortal “Seether” is. The Chicago band—singer/guitarists Nina Gordon and Louise Post, backed by Steve Lack and Jim Shapiro—formed just two years earlier but had figured out their sound right away. The crux of the AC/DC-inspired American Thighs, their debut for Minty Fresh, is damn heady guitar playing, mountains of distortion and a catchiness most grunge-adjacent, hard-rocking albums were short on at the time. Heaviness was a weapon for Veruca Salt, who crafted sugary, punishing licks on “Number One Blind,” “Victrola” and “Spiderman ‘79.” American Thighs is an album built on contradictions, existing as this infectious tapestry of brutality and innocence collapsing into each other (Veruca Salt is, of course, a character in a Roald Dahl novel). Gordon and Post’s harmonies remain pivotal 30 years later, and you can hear them in the work of active bands like Horsegirl, Wednesday, Soccer Mommy, Momma and so many more. —Matt Mitchell

27. The Cranberries: No Need to Argue

Since the presidential election, I’ve been listening to the Cranberries’ sophomore album, No Need to Argue, more than usual, remembering all the reasons why I love Dolores O’Riordan’s voice more than anyone else’s—especially in the wake of such a consequential, enraging precedent. The record, which came out on October 3rd, 1994, was a darker, more fatigued rendition of Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?—an application of far more distortion and plenty more agony. Though it outsold its predecessor by more than 10 million units, No Need to Argue didn’t have the immediacy of singles like “Linger” or “Dreams.” No, No Need to Argue had something bigger, bolder—it had “Zombie,” and that was all it needed. O’Riordan wrote about love no longer being enough in “Zombie,” when she sang through her grief for the young children killed in bombings during the Troubles. “Another mother’s breakin’ heart is taking over,” she sang. “When the violence causes silence, we must be mistaken.” On writing “Zombie,” O’Riordan said that she remembered “seeing one of the mothers on television, just devastate,” that she “felt so sad for her, that she’d carried him for nine months, been through all the morning sickness, the whole thing, and some… prick, some airhead who thought he was making a point, did that.” It’s eerie, or maybe just sadly topical, that No Need to Argue feels as urgent now as it did 30 years ago, something O’Riordan gnaws at through her mentioning of the 1916 Easter Rising in “Zombie.” How can we go back to the place we never left? Specters of evil sew their massacres across generations. It’s the shapes and language that change. Some of us have just gotten better at noticing the signs. —Matt Mitchell

Since the presidential election, I’ve been listening to the Cranberries’ sophomore album, No Need to Argue, more than usual, remembering all the reasons why I love Dolores O’Riordan’s voice more than anyone else’s—especially in the wake of such a consequential, enraging precedent. The record, which came out on October 3rd, 1994, was a darker, more fatigued rendition of Everybody Else is Doing It, So Why Can’t We?—an application of far more distortion and plenty more agony. Though it outsold its predecessor by more than 10 million units, No Need to Argue didn’t have the immediacy of singles like “Linger” or “Dreams.” No, No Need to Argue had something bigger, bolder—it had “Zombie,” and that was all it needed. O’Riordan wrote about love no longer being enough in “Zombie,” when she sang through her grief for the young children killed in bombings during the Troubles. “Another mother’s breakin’ heart is taking over,” she sang. “When the violence causes silence, we must be mistaken.” On writing “Zombie,” O’Riordan said that she remembered “seeing one of the mothers on television, just devastate,” that she “felt so sad for her, that she’d carried him for nine months, been through all the morning sickness, the whole thing, and some… prick, some airhead who thought he was making a point, did that.” It’s eerie, or maybe just sadly topical, that No Need to Argue feels as urgent now as it did 30 years ago, something O’Riordan gnaws at through her mentioning of the 1916 Easter Rising in “Zombie.” How can we go back to the place we never left? Specters of evil sew their massacres across generations. It’s the shapes and language that change. Some of us have just gotten better at noticing the signs. —Matt Mitchell

26. Digable Planets: Blowout Comb

Digable Planets—Ishmael “Butterfly” Butler, Craig “Doodlebug” Irving” and Mariana “Ladybug Mecca” Vieira—only made two studio albums together in their initial eight-year run as a rap trio. But their final LP, Blowout Comb, is simply one of the sharpest hip-hop projects of the 1990s altogether. They brought in folks like Guru, Sarah Anne Webb, Jeru the Damaja, DJ Jazzy Joyce and Monica Payne to fill out their Dave Darlington-co-produced tracklist, which featured all-time tracks like “Black Ego” and “Jettin’.” Deeper cuts, like “9th Wonder” and “Graffiti” are jazz-rap totems, and Digable Planets sound exceptional on them. Blowout Comb was a level-up for the trio, who graduated into bold, political verses and jammy, acid jazz tempests that placed conversations around Black communities front-and-center. Sampling everyone from the Meters to James Brown, Roy Ayers, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, the Headhunters and Motherlode while nurturing a career-defining, orchestral ensemble of bass guitars, saxophones, trumpets, vibraphone, cello, and voices from nearly 30 different musicians, Blowout Comb is simply one of rap’s greatest codas. —Matt Mitchell

Digable Planets—Ishmael “Butterfly” Butler, Craig “Doodlebug” Irving” and Mariana “Ladybug Mecca” Vieira—only made two studio albums together in their initial eight-year run as a rap trio. But their final LP, Blowout Comb, is simply one of the sharpest hip-hop projects of the 1990s altogether. They brought in folks like Guru, Sarah Anne Webb, Jeru the Damaja, DJ Jazzy Joyce and Monica Payne to fill out their Dave Darlington-co-produced tracklist, which featured all-time tracks like “Black Ego” and “Jettin’.” Deeper cuts, like “9th Wonder” and “Graffiti” are jazz-rap totems, and Digable Planets sound exceptional on them. Blowout Comb was a level-up for the trio, who graduated into bold, political verses and jammy, acid jazz tempests that placed conversations around Black communities front-and-center. Sampling everyone from the Meters to James Brown, Roy Ayers, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, the Headhunters and Motherlode while nurturing a career-defining, orchestral ensemble of bass guitars, saxophones, trumpets, vibraphone, cello, and voices from nearly 30 different musicians, Blowout Comb is simply one of rap’s greatest codas. —Matt Mitchell

25. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds: Let Love In

Thanks to “Red Right Hand” appearing in Dumb and Dumber, Nick Cave’s Let Love In has remained a part of me for most of my life—even if I didn’t have a name to go with the voice until adulthood. Let Love In was Cave’s eighth album with the Bad Seeds, and it’s still one of their best LPs to-date. Only Cave could make his pitch-black humor so affectionate, and there’s a striking sense of urgent intimacy scattered across songs like “Do You Love Me?” and “Lay Me Low.” Let Love In is the Bad Seeds at their most whimsical, as they sound like a battalion of lounge singers tripping over their drinks, only to sometimes erupt after turning the volume knob a little too far to the right. “Loverman” is quiet-loud-quiet perfection, while “Nobody’s Baby Now” is, without a doubt, the best song Cave wrote in the 1990s. All of the prior melodrama on Bad Seeds records turns into inimitable splendor, as the band becomes resound while circling an apex like a choir of blood-hungry sharks. Let Love In is tantalizingly moody and beautiful, soaked in chain-gang vocals and romantic piano melodies. —Matt Mitchell

Thanks to “Red Right Hand” appearing in Dumb and Dumber, Nick Cave’s Let Love In has remained a part of me for most of my life—even if I didn’t have a name to go with the voice until adulthood. Let Love In was Cave’s eighth album with the Bad Seeds, and it’s still one of their best LPs to-date. Only Cave could make his pitch-black humor so affectionate, and there’s a striking sense of urgent intimacy scattered across songs like “Do You Love Me?” and “Lay Me Low.” Let Love In is the Bad Seeds at their most whimsical, as they sound like a battalion of lounge singers tripping over their drinks, only to sometimes erupt after turning the volume knob a little too far to the right. “Loverman” is quiet-loud-quiet perfection, while “Nobody’s Baby Now” is, without a doubt, the best song Cave wrote in the 1990s. All of the prior melodrama on Bad Seeds records turns into inimitable splendor, as the band becomes resound while circling an apex like a choir of blood-hungry sharks. Let Love In is tantalizingly moody and beautiful, soaked in chain-gang vocals and romantic piano melodies. —Matt Mitchell

24. Built to Spill: There’s Nothing Wrong With Love

There’s Nothing Wrong With Love starts by clearing its throat: There’s a little noodling and faint clatter before the song proper starts, and the off-the-cuff vibe is intentional. “It was a little bit of a reaction to what was happening in music, where grunge was really taking off with Nirvana and all that stuff,” Martsch told Uproxx. “It’s a lot of clean guitars and it’s not grungy at all. It doesn’t sound tough. There’s no attitude to it. It’s just kind of sweet and straightforward.” Straightforward undersells it, however. “In the Morning” makes it a minute and a half into its strummy singalong before abruptly slowing way down and expanding into a massive riff. The timeless fan favorite “Car” is a sweet and melancholic medication that smacks into snotty verses before sliding into an unexpected interlude of dramatic strings. There’s a wide-eyed spirituality, images from childhood swirled into adulthood, recorded as a kind of reaction to the cresting grunge wave. “Twin Falls” strolls through Martsch’s childhood, the rare biographical song, exceedingly tender and affecting. The K Records influence is still there, but filtered through Martsch’s stoned stargazing. “Isn’t it strange that I can dream / Isn’t it strange that I have brain activity,” Martsch muses on “Cleo.” A lot of the lyrics fall into Martsch’s tendency to be coy and cryptic, treating the lyrics as secondary to the melodies. However, some of the most memorable line deliveries come from this album. On “Distopian Dream Girl,” Martsch says, “My stepfather looks / Just like David Bowie but he hates David Bowie / I think Bowie’s cool / I think Lodger rules, my stepdad’s a fool.” It rocks. There’s Nothing Wrong With Love is open-hearted and unhurried. —Keegan Bradford

There’s Nothing Wrong With Love starts by clearing its throat: There’s a little noodling and faint clatter before the song proper starts, and the off-the-cuff vibe is intentional. “It was a little bit of a reaction to what was happening in music, where grunge was really taking off with Nirvana and all that stuff,” Martsch told Uproxx. “It’s a lot of clean guitars and it’s not grungy at all. It doesn’t sound tough. There’s no attitude to it. It’s just kind of sweet and straightforward.” Straightforward undersells it, however. “In the Morning” makes it a minute and a half into its strummy singalong before abruptly slowing way down and expanding into a massive riff. The timeless fan favorite “Car” is a sweet and melancholic medication that smacks into snotty verses before sliding into an unexpected interlude of dramatic strings. There’s a wide-eyed spirituality, images from childhood swirled into adulthood, recorded as a kind of reaction to the cresting grunge wave. “Twin Falls” strolls through Martsch’s childhood, the rare biographical song, exceedingly tender and affecting. The K Records influence is still there, but filtered through Martsch’s stoned stargazing. “Isn’t it strange that I can dream / Isn’t it strange that I have brain activity,” Martsch muses on “Cleo.” A lot of the lyrics fall into Martsch’s tendency to be coy and cryptic, treating the lyrics as secondary to the melodies. However, some of the most memorable line deliveries come from this album. On “Distopian Dream Girl,” Martsch says, “My stepfather looks / Just like David Bowie but he hates David Bowie / I think Bowie’s cool / I think Lodger rules, my stepdad’s a fool.” It rocks. There’s Nothing Wrong With Love is open-hearted and unhurried. —Keegan Bradford

23. Nirvana: MTV Unplugged in New York

MTV Unplugged in New York is Nirvana unlike we’ve ever seen or heard them before, and it’s an absolutely mesmerizing start to a night that redefined how we think about and remember them. That’s not to say that Nirvana’s Unplugged session was a seamless, flowing production. Far from it. While behind-the-scenes accounts and the filmed drama between songs documents just how quickly the evening could’ve—or maybe even should’ve—headed south for Nirvana, the fact that the night turned into such a compelling, cohesive performance confirms that Kurt Cobain and his bandmates had a thoughtful, if at times muddied, vision for the show. Much of the song selection speaks to that. The murkier “Come as You Are,” the lone hit played off Nevermind, proved far more appropriate than that record’s more explosive singles, Dave Grohl’s harmonies from behind the kit fitting the tone of a dirgelike evening. “All Apologies,” not yet a single, was a no-brainer inclusion over “Heart-Shaped Box” and slid right into the almost psychedelic sound of the set. Stripped of their volume dial, the band discovered other dynamics to tap into. On the aforementioned “Pennyroyal Tea,” Cobain shredded his throat on the choruses to reinvent the contrast usually generated by three bandmates and a screaming Pat Smear in concert. Touring cellist Lori Goldston joined the band on several songs, including “Something in the Way,” where her bowing and Cobain’s repeated humming duet moodily under the studio’s blue-tinted lighting. —Matt Melis

MTV Unplugged in New York is Nirvana unlike we’ve ever seen or heard them before, and it’s an absolutely mesmerizing start to a night that redefined how we think about and remember them. That’s not to say that Nirvana’s Unplugged session was a seamless, flowing production. Far from it. While behind-the-scenes accounts and the filmed drama between songs documents just how quickly the evening could’ve—or maybe even should’ve—headed south for Nirvana, the fact that the night turned into such a compelling, cohesive performance confirms that Kurt Cobain and his bandmates had a thoughtful, if at times muddied, vision for the show. Much of the song selection speaks to that. The murkier “Come as You Are,” the lone hit played off Nevermind, proved far more appropriate than that record’s more explosive singles, Dave Grohl’s harmonies from behind the kit fitting the tone of a dirgelike evening. “All Apologies,” not yet a single, was a no-brainer inclusion over “Heart-Shaped Box” and slid right into the almost psychedelic sound of the set. Stripped of their volume dial, the band discovered other dynamics to tap into. On the aforementioned “Pennyroyal Tea,” Cobain shredded his throat on the choruses to reinvent the contrast usually generated by three bandmates and a screaming Pat Smear in concert. Touring cellist Lori Goldston joined the band on several songs, including “Something in the Way,” where her bowing and Cobain’s repeated humming duet moodily under the studio’s blue-tinted lighting. —Matt Melis

22. Tori Amos: Under the Pink

In 1992, Tori Amos introduced herself with Little Earthquakes, a really terrific debut album primed to make a meal out of the singer-songwriter side of cutting-edge rock music. But Amos is at her best on the subsequent Under the Pink, a breakthrough record if there ever was one—a startlingly successful project that sold a few million copies, garnered a Platinum status in the United States and featured a backing band of Steve Caton, John Philip Shenale, George Porter Jr., Paulinho da Costa, Carlo Nuccio and Trent Reznor. Few tracks are as ubiquitous in ‘90s lore as “Cornflake Girl” and “Pretty Good Year,” with the former reaching #7 on Billboard’s Bubbling Under Hot 100 Singles chart. Amos, ever the progeny of Joni Mitchell, became a star on Under the Pink—an album so honest and strident in its own empowerment, tackling religious repression and sexuality while admonishing patriarchal divisions. Wedged in-between the breakouts of PJ Harvey and Fiona Apple, Amos’s work is profound, confessional and catapulted into brilliance not by expectation but by ambition. —Matt Mitchell

In 1992, Tori Amos introduced herself with Little Earthquakes, a really terrific debut album primed to make a meal out of the singer-songwriter side of cutting-edge rock music. But Amos is at her best on the subsequent Under the Pink, a breakthrough record if there ever was one—a startlingly successful project that sold a few million copies, garnered a Platinum status in the United States and featured a backing band of Steve Caton, John Philip Shenale, George Porter Jr., Paulinho da Costa, Carlo Nuccio and Trent Reznor. Few tracks are as ubiquitous in ‘90s lore as “Cornflake Girl” and “Pretty Good Year,” with the former reaching #7 on Billboard’s Bubbling Under Hot 100 Singles chart. Amos, ever the progeny of Joni Mitchell, became a star on Under the Pink—an album so honest and strident in its own empowerment, tackling religious repression and sexuality while admonishing patriarchal divisions. Wedged in-between the breakouts of PJ Harvey and Fiona Apple, Amos’s work is profound, confessional and catapulted into brilliance not by expectation but by ambition. —Matt Mitchell

21. Mary J. Blige: My Life

The quantum leap Mary J. Blige made from her debut album, What’s the 411?, and her sophomore LP, My Life, was nothing short of a breakthrough that established her as the rightful “Queen of Hip-Hop Soul.” Singing about drug and alcohol abuse, her abusive relationship with K-Ci Hailey and clinical depression, Blige—who wrote on 14 of the album’s 17 tracks—took a personal turn on My Life and never looked back, soaring up the charts (#7 on the Billboard 200) with a laundry-list of colleagues. The sampling on My Life deserves all the praise, as Blige and her production team collage work from Curtis Mayfield (“Give Me Your Love”), Marvin Gaye (“I Want You”), Barry White (“It’s Ecstasy When You Lay Down Next to Me”), Teddy Pendergrass (“Close the Door”), Al Green (“Free at Last”) and the Mary Janes Girls (“All Night Long”) into something undoubtedly her. It’s not just an R&B and hip-hop treasure; it’s a career-defining statement. —Matt Mitchell

The quantum leap Mary J. Blige made from her debut album, What’s the 411?, and her sophomore LP, My Life, was nothing short of a breakthrough that established her as the rightful “Queen of Hip-Hop Soul.” Singing about drug and alcohol abuse, her abusive relationship with K-Ci Hailey and clinical depression, Blige—who wrote on 14 of the album’s 17 tracks—took a personal turn on My Life and never looked back, soaring up the charts (#7 on the Billboard 200) with a laundry-list of colleagues. The sampling on My Life deserves all the praise, as Blige and her production team collage work from Curtis Mayfield (“Give Me Your Love”), Marvin Gaye (“I Want You”), Barry White (“It’s Ecstasy When You Lay Down Next to Me”), Teddy Pendergrass (“Close the Door”), Al Green (“Free at Last”) and the Mary Janes Girls (“All Night Long”) into something undoubtedly her. It’s not just an R&B and hip-hop treasure; it’s a career-defining statement. —Matt Mitchell

20. Soundgarden: Superunknown

By the time Soundgarden put Superunknown out into the world, no one knew that grunge rock was facing numbered days. Just a month before Kurt Cobain would be found dead in the greenhouse of his Seattle home, Chris Cornell, Kim Thayil, Ben Shepherd and Matt Cameron made one of the genre’s most important works—a project warmed by its own range, which cycles through fits of hard-rock and volcanic, one-of-a-kind, anxiety-inducing music. Thayil’s stoner-metal style converges with Cornell’s pessimistic lyrics for a bevy of doomy, energetic tones ripe for a soon-uncertain landscape of heavy music. It’s the most ambitious version of Soundgarden ever, a remarkable turn from Badmotorfinger that relishes in its own crushing annihilation. Cornell’s songwriting lent its focus to substance abuse, suicide and the trifecta of death, alienation and revenge—transported into a catchiness that turns thorny songs like “Black Hole Sun” and “Spoonman” into generational feats of stardom. Superunknown is a tempest and a car crash that’s impossible to look away from. —Matt Mitchell

By the time Soundgarden put Superunknown out into the world, no one knew that grunge rock was facing numbered days. Just a month before Kurt Cobain would be found dead in the greenhouse of his Seattle home, Chris Cornell, Kim Thayil, Ben Shepherd and Matt Cameron made one of the genre’s most important works—a project warmed by its own range, which cycles through fits of hard-rock and volcanic, one-of-a-kind, anxiety-inducing music. Thayil’s stoner-metal style converges with Cornell’s pessimistic lyrics for a bevy of doomy, energetic tones ripe for a soon-uncertain landscape of heavy music. It’s the most ambitious version of Soundgarden ever, a remarkable turn from Badmotorfinger that relishes in its own crushing annihilation. Cornell’s songwriting lent its focus to substance abuse, suicide and the trifecta of death, alienation and revenge—transported into a catchiness that turns thorny songs like “Black Hole Sun” and “Spoonman” into generational feats of stardom. Superunknown is a tempest and a car crash that’s impossible to look away from. —Matt Mitchell

19. Grant Lee Buffalo: Mighty Joe Moon

A heavy, Americana-peddling rock band from Los Angeles, Grant Lee Buffalo’s initial run only lasted eight years, but they dropped four very good records in that span—including the career-defining Mighty Joe Moon, a mythological token of road-worn, rural folklore. Where “Lone Star Song” stretches out and lays the riffs on thick, “Mockingbirds” is a gentle, crushing ballad proving that vocalist and guitarist Grant Lee Phillips was one of the decade’s strongest lyricists. Wedging itself someplace within the ecology of New Morning and Rust Never Sleeps, Mighty Joe Moon is a squall of distorted, blistering guitars and idealistic, hungry, genre-bending liveliness that reclaims Van Morrison’s “To be born again” proverb and turns vignettes of a doomy, cynical America into something worth putting faith behind. Grant Lee Buffalo didn’t last, but Mighty Joe Moon carries on as a record that lies in bed with the devil but yearns for the divine—a true rock ‘n’ roll contradiction if there ever was one. —Matt Mitchell

A heavy, Americana-peddling rock band from Los Angeles, Grant Lee Buffalo’s initial run only lasted eight years, but they dropped four very good records in that span—including the career-defining Mighty Joe Moon, a mythological token of road-worn, rural folklore. Where “Lone Star Song” stretches out and lays the riffs on thick, “Mockingbirds” is a gentle, crushing ballad proving that vocalist and guitarist Grant Lee Phillips was one of the decade’s strongest lyricists. Wedging itself someplace within the ecology of New Morning and Rust Never Sleeps, Mighty Joe Moon is a squall of distorted, blistering guitars and idealistic, hungry, genre-bending liveliness that reclaims Van Morrison’s “To be born again” proverb and turns vignettes of a doomy, cynical America into something worth putting faith behind. Grant Lee Buffalo didn’t last, but Mighty Joe Moon carries on as a record that lies in bed with the devil but yearns for the divine—a true rock ‘n’ roll contradiction if there ever was one. —Matt Mitchell

18. TLC: CrazySexyCool

A solidly ‘90s creation, CrazySexyCool defined an era of scratchy hip-hop beats and shimmery R&B production that effectively changed the game for girl groups in perpetuity. (Oh, and it also spawned a set of all-time bangers: “Waterfalls,” “Creep” and “Diggin’ On You.”) This epic from Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes and Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas marked a high point in the group’s one decade of music-making as a trio, preceding Lopes’ death in 2002. Now, CrazySexyCool continues to age finely, providing a nostalgic capsule of well-crafted, sultry, feminine pop anthems for all time. —Annie Nickoloff

A solidly ‘90s creation, CrazySexyCool defined an era of scratchy hip-hop beats and shimmery R&B production that effectively changed the game for girl groups in perpetuity. (Oh, and it also spawned a set of all-time bangers: “Waterfalls,” “Creep” and “Diggin’ On You.”) This epic from Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes and Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas marked a high point in the group’s one decade of music-making as a trio, preceding Lopes’ death in 2002. Now, CrazySexyCool continues to age finely, providing a nostalgic capsule of well-crafted, sultry, feminine pop anthems for all time. —Annie Nickoloff

17. Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth: The Main Ingredient

Perhaps the greatest jazz rap album of its era, The Main Ingredient marked Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth’s second and final studio album together as a duo but left its mark on hip-hop for good. Rock and Smooth trade verses on every track, welcoming the voices of Rob-O, Crystal Johnson, Vinia Mojica, Deda and Grap Luva into their world in the process. “Take You There” is seductive and focused, while “I Get Physical” is a titanic, fantastic measure of bombast. The duo’s self-produced sound put them in the same conversations as De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest, but there’s something about tracks like “Sun Won’t Come Out” and “In the House” that carried the momentum from their debut album, Mecca and the Soul Brother, forward. With smart rhymes and pleasurable beats, The Main Ingredient sounds as brand-new now as it did 30 years ago, and Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth remain defining figures of the East Coast’s faction of rap’s greatest era. It was one of J Dilla’s favorite records, a compliment of the highest honor. —Matt Mitchell